These are generally the most widely read free posts. I tend to make policy-related posts free and save actionable investment and market related posts for subscribers. I think the subscriber stuff is the good stuff, in terms of understanding the housing market for your own sake, so these posts are sort of the starting line-up of the B-team.

The subtitles are linked to the posts.

January

This series technically started in December 2023.

Hsieh, Moretti, Shiller, and the Rest (Part 1, 2, 3, 4)

This series asserts that inadequate supply is the headline reason for high housing costs, not agglomeration economies. This is a theme that I revisited a lot this year.

Occasionally, in a dark alley, someone is met with an ultimatum. “Give me all your money or I’ll shoot.” There isn’t a GDP category for that. It doesn’t change total production, hours worked, aggregate consumption. How could you even statistically confirm that this was bad? We don’t react to an increase in muggings by elevating the status of dark alleys and studying what makes them so special that people would risk a mugging to walk into them.

A Brief Technical Review of the Alternative Housing Story

This is probably a decent single-post introduction to the basic approach I use here at EHT.

February

Homeownership is down more than you thought.

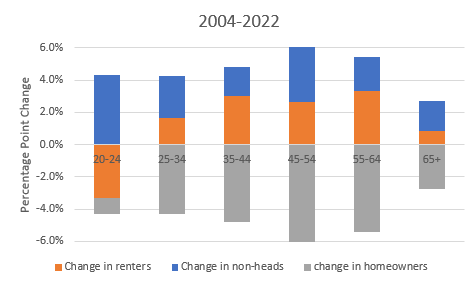

This post makes the point that the reason homeownership rates seem stable is (1) age demographics and (2) that the housing shortage is so bad that for every head of household that has to rent instead of buying, there is another person who has to be a roommate instead of the head of a household.

Disgusting

Aesthetics are the last refuge of a NIMBY. It is a complaint that can be universally applied and is unanswerable…Aesthetics are status. By that, I don’t mean that people with high status like or appreciate nice things. I mean that their expression is a reflection of status…One might go so far as to observe that the more arbitrary the standard, the more strong and sincere (truly, sincere) it will be felt…“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” Aesthetics are one way that we fool ourselves. Aesthetics interrupt the opportunity for reason. It is difficult to reason with someone who sincerely but unwittingly isn’t engaged with it.

That will make housing reform difficult. There will be many residents who oppose changes. They will be angry because they will feel steamrolled by changing policies. But, they will be unable to offer an alternative process, because aesthetics will be the only channel through which they are able to engage with change. They will be sincere in their opposition and sincerely aggrieved when change happens.

Cantankerous 3 Part Series

Part 1: Market Power in Housing Construction

Put down that ridiculous Quintero paper. Housing production hasn’t been reduced because of market concentration and oligopolistic power among the homebuilders. If you, even for a second, might have thought that homebuilders were purposefully throttling sales between 2008 and 2020, please, I cannot stress this enough, touch grass.

Part 2: Fear of Affordable Housing

There is no realistic amount of new supply that is going to cause rents across a whole metropolitan area to decline by double digit percentages in a single year.

Part 3: The Minneapolis Miracle

Unfortunately, this piece has been used by NIMBcompoops to claim that even I don’t think housing supply is lowering costs.

A claim I keep seeing popping up is the idea that Minneapolis is a notable example of effective supply side reforms in housing.

I am afraid that, currently, it is not.

March

Why more housing appears to make things worse

If your problem is inelastic supply, then the casual observer will think there is a problem with too much demand and a housing market that is too cyclical and getting worse. A supply problem looks like a cyclical problem, even though it is quite the opposite.

In the worst cities, where cyclical changes in new housing production can’t begin to keep up with normal increases in demand for housing (from rising incomes, births minus deaths, etc.), the very small increase in housing production that is associated with cyclical expansions will be systematically associated with lower population growth and more regional displacement.

For people who have lived their entire lives in those cities, all of their personal experience will be screaming “added supply hurts!”

Updating my priors on missing middle

If we’re thinking about the sterile urban housing landscape that 20th century zoning has left us as a blank slate to build on, maybe I’ve had it backwards. Maybe this will be the “missing middle” century, and more skyrise condos and entry level single-family neighborhoods can also be parts of the broader movement.

April

2024 IS the counterfactual to 2009!

The market after the Covid housing boom can’t possibly be a repeat of 2008. Before 2008, a severe shortage of urban housing in the “Closed Access” cities caused low tier housing costs in those cities to rise. Our response in 2008 was to cut off mortgage lending for all low tier neighborhoods. That caused low tier prices to crash everywhere. The net result was that from 1998 to 2013, housing costs in the Closed Access cities increased much more than the rest of the country. Low tier housing costs in the Closed Access cities increased much more than high tier housing costs, because of the supply crisis, but they were also discounted because of the mortgage crackdown. The two factors cancelled each other out. But, since the rest of the country didn’t have a supply crisis yet, in the other cities, there was just a low-tier collapse.

(Not covered in this post, but since 2013, the mortgage crackdown combined with the pre-existing obstruction to city-building every city shares created a nationwide housing shortage. So, today, low tier housing costs are high in every city, even with the mortgage discount. We’re all Closed Access now! Or as proper economists would say, we’re all superstars!)

Why The Economy Isn't Working

In this short post, I simply use IRS income data and Zillow rent data to show that rent inflation has stolen all the recent income gains from families with lower incomes.

Household Size and the Housing Stock

This is a post I keep going back to. It is the most read post from the first half of the year. The long and the short of it is that in 2008 a decades-long linear trend in adults per house suddenly shifted.

The first post of 2025 will reference this post. It is one of the reasons why I think the housing shortage is at least 15 million units, and, in fact, consumers will be demanding that many additional units over the next several years until we ban every type of housing that could satisfy that demand.

We are already 15 years into a cultural and economic battle that is so important, it turned the direction of adults per house upward for, likely, the first time since the start of the industrial revolution. Fifteen years in, by that measure, we have reversed economic progress by nearly 40 years. There is so much ground we have to make up. And, also, the reactionary position will have to continue to dig deeper and get worse - rounding up immigrants, blaming the homeless, stoking fear and distrust of financial institutions. I’m sorry if I’m sounding too shrill. It all happens in slow motion around us, so we adapt to the new normal. But the tent encampments in all the urban parks are a long way from what should be considered normal. We are already deeply into a cultural battle. And you can see that it is a cultural battle, because it is difficult to simply establish a plurality of support to admit obvious things.

Filtering on HGTV

This isn’t necessarily the most read post of the year, but I am proud of this piece. I think this is a rhetorical approach that is positive, and more importantly, true. And, at the risk of embarrassing myself, when I re-read this post, I sometimes get a little bit verklempt.

When homes are filtering, they are blank slates - whether they are decent $400,000 homes that just need some updating, or little shacks threatening to blow over in a hard wind that truly need a major renovation.

Where homes are truly trickling down, they trickle down much faster than we would like them to. Updating and renovating them is work - it’s an important part of the residential investment and the expense of consuming shelter. Yet, the way that plays out for an individual new owner is that there is some house that needs them - that is just the right house for them, but it is less than they need. And, they build it up. They make it better - and more expensive - because it’s there, waiting for them to put their mark on its narrative as a source of shelter for generations.

Filtering - trickling down - where it actually happens is a narrative of rebirth, of regeneration, and of comfortable equilibrium. It is no coincidence that homes across Phoenix sold for 3x their tenants’ incomes in 2002. That coincidence would be impossible….

In the end, trickle down becomes a bottom up process. A process where the leftover “bones” from the “Smith house” become the “soup’s beef stock” for the “Warren house”. “Trickle down” housing is a creative process - an additive process.

May

We need Wall Street in Housing. This is important!

This may be the most important paper I have written for the Mercatus Center. If the developments I fear for in this paper happen, America will be in a bad, bad way. In short, we have spent a century making every individual source of housing illegal. On the margin, there is one form of housing left - single family homes built for rent. That market segment is taking off because there is a huge supply gap for it to fill. There are already proposals to ban it. If we do, that’s it. The game’s over. We will have officially made homelessness public policy. And, I don’t look forward to how that will play out.

Here’s my Mercatus brief, with the data and details.

Here’s a longer background piece I wrote for Liberal Currents.

Here’s a shorter explainer I wrote for Discourse Magazine.

No. Taxpayers didn't bail out Fannie & Freddie

This wasn’t particularly widely read, but it is an important issue that I don’t see anyone else talking about.

Long story short, the federal government didn’t really have to inject $200 billion of cash into Fannie and Freddie in 2008. They didn’t need cash. They just needed a stable marketplace. So, basically, the federal government gave them $200 billion, and lacking anything else to do with it, Fannie and Freddie just gave it back, by buying Treasuries or similar near-cash securities with it.

Unfortunately, right-leaning anti-agency economists and pundits will never stop making the claim that Fannie & Freddie put hundreds of billions of taxpayer dollars at risk. There is still a push to privatize Fannie & Freddie, which, as far as I am concerned is the equivalent of getting rid of them. I consider them to be a sort of financial technology that can only add value as a public utility. We have already destroyed that value. We have over-regulated mortgage financing so much already, I’m not sure that getting rid of them can cause much more damage than we have already created. Mostly, it just makes me sad that supply-side economists have been so obsessed with these relatively benign and even slightly useful agencies that they are typically skeptics about the supply-side crisis that actually exists in housing. IMHO, it is hard for many right-leaning policy influencers to accept the importance of the supply crisis (and the importance of the mortgage crackdown in creating the supply crisis) because they would have to give up their long-standing and wrong obsessions with the federal mortgage agencies.

June

US Residential Housing: A Simple Story in 4 Acts

Act 1: pre-1982 - building and real growth

Act 2: 1982-2007 - regional building constraints, rent inflation, excess value

Act 3: 2007-2012 - credit shock

Act 4: 2012-2024 - nationwide building constraints from the credit shock, nationwide rent inflation, prices inflated from rent and deflated from credit shock

Act 5: 2024-future - New build-to-rent neighborhoods might stem future excess rent inflation and stop additional price appreciation. I think a return to more generous lending to owner-occupiers will be required to reverse it in the mid-to-long term.

YIMBYism will not create housing losses!

At best, we might hope that rents and prices level out for a decade in cities that build. There are a few places, like Dallas and Atlanta, where, briefly during the 2000s building boom, ample construction and relative regional demand slumps led to moderate rent deflation. Supply can’t do that on its own.

Don’t promise that it can. Don’t scare homeowners with the prospect that it will. Don’t write checks on short-term rent trends that your YIMBY butt can’t cash.

Supply has never and will never cause a collapse of prices and rents. It causes stability. It causes moderation. And, when all is said and done, that is likely for the best.

Put all those “wow” claims on the shelf. The only carrot we have to offer is stability and moderation. That’s a really good carrot! It’s the most important carrot! It’s the only outcome that is a solution.

RealPage, Collusion, and Rents

This post has two parts. The first part dismisses the claims that rent management software is an important source of recent rent inflation.

On the RealPage kerfuffle:

And, more recently, The American Prospect, has published an article that fully discards any limits to scale that were in the Propublica article. “By now, you have probably heard of Yieldstar, the private equity–owned software that numerous plaintiff’s attorneys, tenant advocates, and state attorneys general say is actually a front for a sprawling nationwide cartel that fixes rent prices to ludicrous heights and has caused the cost of an apartment to surge between 50 and 80 percent over the past seven years in several of the markets where the software is employed.”

This is laughable. This is like claiming that you could lasso the moon. Vacancy rates across the country are in the single digits. For landlords to be able to collude to raise rents 50% to 80%, they would need to hold tens of millions of units off the market to raise rents that much. I estimate a nationwide shortage of something like 20 million units, and, yes, if we had those units, it might reverse 50% to 80% of rent inflation. We don’t have the units.

These claims are so outrageous and so explicit, that it is clear that their authors are simply incurious about what they are asserting. They don’t have a misconception. They simply aren’t conceiving anything. Just like with the mythological supply glut in the 2000s, there is nothing to debunk. The purveyors aren’t concerned with the facts that they imply.

I then discuss how the RealPage nonsense mirrors the moral panic of the pre-2008 market. In this chart, I show home price trends in metro areas where home prices were 1 standard deviation above and below the national average. And, then, I show the effect that the actual literature on the lending boom claims that excess lending had on home prices.

The existing literature literally manually removes the differences between metro areas. It’s like measuring the effects of a flood after controlling for the amount of rain.

To summarize, according to GKM: The 4% drop associated with reckless lending “played a large role in the crisis”. The 40% drop in cities that weren’t even expensive? They’re sure if we looked, we’d find a standard explanation.

I think I may be being too hard on American Prospect, because America’s top economists, vetted by its top reviewers, and published in a top journal, thought it made sense to just intuit that in the physical world we live in of 2x4s, concrete, and gypsum board, every city in the country pulled enough of that into shelter in just a couple of years to lower the aggregate value of all real estate by 40% or more.

Maybe RealPage could single-handedly increase rents by 80%. Hell, maybe I could go out on my porch and blow a song on my kazoo and cause the universe to implode. I haven’t checked the math, but the intuition checks out.

Joseph Stiglitz on Housing in Nevada

This was the second most read post from the first 6 months of 2024. This sort of hits the same notes as the previous post. Unfortunately, our leading economists have been treating certain false empirical assertions as if they are canon. And it appears that none of them ever just bothered to look.

In an interview with Tyler Cowen:

STIGLITZ: So, the issue isn’t the amount of credit. It was the allocation of credit. If they had used that credit for productive uses, how much better our economy would have been.

COWEN: Well, we built a lot of homes, right? It’s turned out we’ve needed them. The home prices that looked crazy in 2006 now seem somewhat reasonable.

STIGLITZ: A lot of them were built in the wrong place and were shoddy. I used to joke that there were a huge number of homes built in the Nevada desert, and the only good thing about them is they were built so shoddily that they won’t last that long.

I simply point out that there was no building boom in Nevada.

And the unusual rise in debt outstanding in Nevada came mostly after home prices had spiked and construction had sharply turned lower.

Cowen frequently makes the valid point that if you look for it, there is existing literature on practically any question you might ask. It is so odd that there is a stark reality staring us in the face and the entire academy has spent two decades pretending there is a different reality, and all of them, individually, seem to have decided not to bother to look.

Tomorrow I will post links to the most read posts from July to December.

Nice, nice. Halfway through your victory lap for the year. I had forgotten about the RealPage kerfluffle and the idiocy of Stiglitz on the housing "bubble." Both topics seem to have faded away, and unless there's some sort of stupid uprising next year I think that Wall Street will still play a useful, albeit small, role in single family housing next year.

The general state of YIMBY vs NIMBY seems unclear to me, and I think this shows up in the data you've been presenting. The California miracle in Builder's Remedy and ADU regulations may take a long to manifest as a substantial force in new unit production. It's hard to assess how it will play out in the courts and political blowback. Here in Massachusetts, the YIMBY movement feels stalled.