A Brief Technical Review of the Alternative Housing Story

This may be a repeat for regular readers, but maybe this post can serve as a single-source summary of some of the quantitative points of my Great Recession revised history.

Let’s start with Figure 1, metropolitan housing permits per capita. I’m going to look at Los Angeles (a “Closed Access” city), Atlanta (a typical city), and Phoenix (a “Contagion” city) here. Really, on the supply side, there are just two stories here. Los Angeles approves far too few homes. Phoenix and Atlanta approved a lot of homes before the Great Recession. Even today, after substantial recovery from the lows, they have approved new homes at less than half the rate they did before the Great Recession, but that is still more than double the rate that Los Angeles does.

Many national aggregate statistics are distractions, because most of the important elements of the American housing market and the American economy are these extreme and historically anomalous regional differences.

Also, before I move on, I’ll note one issue that creates errant conclusions. Looking at these three metro areas on a percentage growth basis (Figure 2) makes it look like LA has had a building boom. Compared to the 1998 peak, building rose by 50% during the 2000s expansion and returned their again in the 2010s.

Construction is so low in LA, it means nothing. During its peak construction years, LA has been losing population. That makes sense. It’s permanent level of housing permit approvals is the level of a shrinking or stagnant city. Nothing x 50% = nothing. But, to the eyes of many locals it is a building boom. Even policymakers make this mistake. In Shut Out, I cited a quote from Boston Fed chief Eric Rosengren in 2015 about Boston, making the same mistake. He suggesting that “bubble” conditions called for rate hikes because there were a lot of cranes at work in Boston. Boston has housing permitting rates and population stagnation similar to LA’s. It is an unfortunately widespread misperception.

I have written about this problem. In the Closed Access cities, the supply response is not zero, but it is practically zero. So, when cyclical demand for housing increases, supply can’t even increase enough to maintain stable population. A handful of American cities have housing markets that are so undersupplied that population growth is negatively correlated with housing construction. For each percentage point increase in demand for homes per capita, those cities only approve a small fraction of a percentage point increase in homes. This unfortunately lends false support for the notion that building booms create displacement and, thus, more supply can’t solve the housing problem.

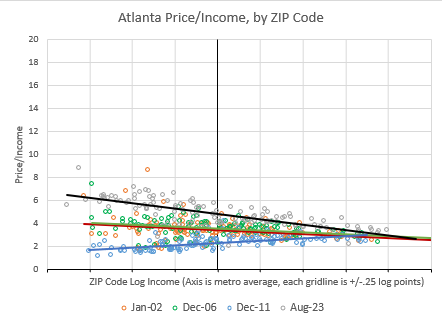

Anyway, on to these cities. In the following figures, there are 4 scatterplots. The x-axis is the relative average income of each ZIP code and the y-axis is the median price/income in each ZIP code. Four points in time are compared: January 2002, December 2006, December 2011, and August 2023.

Los Angeles

In 2002, home values in LA were a bit higher in poor ZIP codes than in richer ZIP codes, but not exceedingly so. All of the increase in home prices between 2002 and 2006 were income-sensitive. The lower the incomes, the higher the price appreciation. This was misinterpreted to be evidence that loose credit was the cause of rising prices (and of the pitiful little building boom in LA).

In one of my Mercatus papers, I found that there was a bit of a credit boom at the time, and it was associated with some rising prices that subsequently reversed. But, it wasn’t particularly important for markets like LA. The reason for that asymmetrical price appreciation between 2002 and 2005 (which coincided with a spike of outmigration from LA of its poorest residents) is that undersupplied housing creates a regressive cost pattern, which I described in another Mercatus paper.

Initially, from 2006 to 2011, the regressive price appreciation reversed and by 2011 LA looked like it’s old 2002 self again. But, if my paper about price trends during the 2000s doesn’t convince you that the credit boom was an unimportant factor in LA real estate appreciation, the following decade should. Because, now, with none of the mortgage lending excesses of the 2000s, LA is right back where it was in 2006.

Atlanta

Atlanta built amply before 2008. And, home price/income ratios across Atlanta’s ZIP codes were exactly the same in 2006 as they had been in 2002. There was a credit boom. But there was no bubble to pop in Atlanta. No building boom (just their regular high level of construction to accommodate a growing city). No price bubble.

Since there was no bubble in Atlanta, the subsequent collapse was not a reversal of anything. In LA, it looked like a reversal of something, but we can see today that it wasn’t. Prices had risen because of inadequate supply, and then prices temporarily were tamped down with mortgage suppression. In Atlanta, it is clear how ridiculous the effects of mortgage suppression were. Devastating.

As you could see in Figure 1, the mortgage bust led to a decade-long construction bust. Atlanta hasn’t been able to approve new homes much faster than LA does. And, so, 15 years later, there is now a bit of a slope to home prices (relative to incomes) in Atlanta, similar to LA in 2002. Now, Atlanta has inadequate housing supply.

Phoenix

In Figure 1, Phoenix looked a lot like Atlanta. The main difference is that before 2008, a lot of those housing refugees out of LA headed to Phoenix, creating a spike in demand for new homes in Phoenix. So, Phoenix had a bit of a true housing bubble. But, remember how that asymmetrical price appreciation in LA was misattributed to a credit boom? As Figure 5 shows, Phoenix didn’t really have that at all. From 2002 to 2005, home prices in Phoenix rose across the metro area. Phoenix didn’t have the supposed tell-tale sign of credit excess. All of the Contagion cities - the cities that truly could claim to have had unsustainable price bubbles - look similar to Phoenix. They don’t have the signature of a credit bubble.

From 2006 to 2011, prices across Phoenix shifted back down. The bubble burst. And, then, on top of that, the new rules against mortgage lending took down low-end home prices just as they did in Los Angeles and Atlanta.

So, in Phoenix and Atlanta, and many other cities, by 2011, price/income ratios were dependably lower in poor neighborhoods than in richer neighborhoods. Making it illegal for residents to buy homes in their own neighborhoods is a very effective (but, alas, temporary) way to make homes “affordable”.

And, as with Atlanta, since mortgage suppression gutted new home construction, by 2023, Phoenix looked a lot like 2002 LA.

One last point about Phoenix. The common myth about the 2000s was that a credit bubble led to price bubbles in the Contagion cities, which drove an unsustainable construction boom. Figure 6 is from “Building from the Ground Up”. Panels are shown for both Nevada and Arizona. On the left axis are home prices and debt per capita, relative to the rest of the US. On the right axis is the rate of new housing permits.

You can see that the myth has it roughly backwards and/or wrong. There wasn’t much of a building boom in either state. When demand outpaced supply, there was a spike in prices, but the spike in prices happened before there was an unusual rise in debts. In fact, the rise in debts happened mostly after prices had peaked and construction was in deep decline.

There's no harm in repeating this--some people might be coming to this information for the first time. The myth of overbuilding in the housing market prior to the Great Recession did great harm to the country as whole---although many areas of the Sunbelt did a better job of recovering from that (even despite the vicious lending standards that are in place now).

And, can I issue a bleg for a post on your take on "rent softening" as it's being reported in conventional media?

An excellent review of how housing-production constraints have savaged America's middle- and lower-income groups.

End property zoning, and pre-approve all housing production.