Hsieh, Moretti, Shiller, and the Rest: Part 4

Previous posts in this series. (1, 2, 3)

This series has been a review of the Agglomeration story of high home prices and the Irrational Exuberance story. They are contradictory stories (value is real vs. price doesn’t match the value) and both are wrong. Both are wrong in a similar way - by assigning the cause of high prices to aspiration, exhilaration, productivity, liquidity, etc. But high prices are caused by inertia and displacement. Housing is draped in endowment effects. The only way prices could be so persistently high is that people are trying to hold on to old things, not because people are irrationally excited about new things.

Households will give up amenities, square footage, etc. to spend a comfortable amount of their budgets on housing. We have done that for generations. Poorer generations didn’t spend more of their incomes on housing. They lived with less.

But households will pay more to keep what they have. To keep close to a good job. To stay near family. Etc.

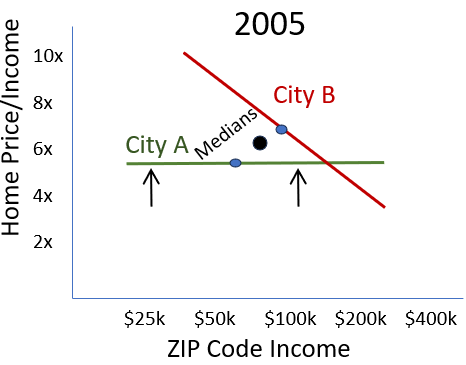

The first 3 figures here were in part 1, to illustrate the changes that happen in a hypothetical economy with 2 cities when one city starts to forbid new housing. Here, I will extend those illustrations to describe the American market over time.

Let’s call Figure 1 1995. Problems in housing access were brewing before then, but that’s about when housing shortages began to bind. Before then, homes were generally affordable, and with minor idiosyncratic differences, home prices across the country settled at 4x income or less just about everywhere - high income or low.

By 2000, the Closed Access cities were City B’s. (NYC, LA, Boston, San Francisco, San Diego, San Jose,… Honolulu if you dig down far enough). There just weren’t enough houses in our “City B’s”. Somebody had to move. They moved to cities where houses can be built.

The way this plays out is that prices move higher until some family decides that regional displacement is less costly than higher housing costs. Those pressures build up onto families with lower incomes.

Figure 3 shows the second order results of this. When the poor families move away, the average income of the remaining families is higher. As the incomes of remainers rise, the price of homes has to keep pushing up to high multiples of those incomes to induce some families to leave.

By 2005, the rate of migration was so strong that it led to something you could call a housing bubble in our “City A’s”. It wasn’t exactly aspirational. Families were moving to City A out of compromise and distress. There were some exuberant investors who did play a Shiller-esque role as secondary characters in that process. In the City As, since the price spike wasn’t due to the specific problem of inadequate supply and income-sensitive migration pressures, prices didn’t change like they do in the Closed Access cities. They mostly moved up across those cities, regardless of income. Since that price inflation was not due to long term supply problems, it was transitory, to use the parlance of the current moment.

Since the income-sensitive price appreciation of the Closed Access cities was misinterpreted as a result of lending, unqualified buyers, and speculation, the political attempts at solving high prices were aimed at lowering home prices in an income-sensitive way in cities with housing booms and ample construction. Since the City As didn’t have that price signature - prices weren’t especially higher in ZIP codes with low incomes - those solutions were aimed at the one problem our City As didn’t have.

Homes in ZIP codes with the lowest incomes now became exceedingly cheap, because the traditional marginal buyers in those ZIP codes had been regulated away. They were still tenants. There was still demand. So, their rents didn’t collapse. But the prices of their homes did.

Since the federal policy responses were meant to quell demand at the low end - borrowers with low incomes that required generous lending - prices declined at the low end, even though that wasn’t City A’s problem.

By 2010, that meant that our “City Bs” were still basically in a state of regressive distress and now our “City As” had the opposite pattern, caused by an opposite type of distress. Now there were cities without enough homes and other cities without enough money or credit. To bubble mongers, the average of those distresses looked great! But two disequilibria are not sustainable, even if they average each other out.

This was the condition that Robert Shiller was benchmarking to in part 2 of the series when he was warning about rising prices in 2015.

Builders don’t build homes whose prices are too low, even if their rents are high. So, for a decade, the sorts of obstructions to building that had been a City B phenomenon started to bind in our “City A’s”. Middle class homes weren’t being built for median-income families that could no longer get mortgages and the limits to multi-unit home building that had been lurking under the surface now became binding. Now, there are Americans choosing to move away from all types of cities, or choosing not to move to them, because of rising rents (and, increasingly, rising prices). And the only group of buyers that can fill the gap are private equity single-family investment firms. Private equity because they can get funding in a post-CFPB world. Single-family because cities don’t approve multi-family easily.

Many people blame that market for pushing up home prices. They want to kill the private equity single-family home market. They would have us follow the American housing story that is now becoming decades old - cutting off our nose to spite our face.

These 6 illustrations, at no time, required a Wall Street residential investment boom (except for the migration booms into the City A’s that briefly overwhelmed their building capacity), urban productivity, speculative investment, or irrationality (outside of policymakers and economists). It just required a popular little devil whispering in ears. “We don’t want those new homes ‘round here. We like it just the way it is.” We don’t need a new wing of behavioral science to explain what’s happening here.

The only thing any of this requires is a plurality of support for obstruction. It isn’t a combination of things in any meaningful way. It’s just one thing. That one thing is necessary and sufficient to create the price patterns we see.

Thanks for the great analysis in an easier to understand cow!

Just a couple of thought which will complicate this picture and may be already under deep discussion somewhere in the literature:

In the City B / City A framework, it is possible that historically the role of City A has been the role of the suburbs of City B. Since 1920 the automobile has reshaped and expanded cities immensely. At some point, rail and commuter lines further increased the ability for cities to expand. Initially those suburban areas had less constraints and more space while offering the same access to job centers. And, as they say, as long as it is within 30 minutes it is all good. But at some point the City B suburbs run out of roads, rails, and places that can still be reasonably called convenient. I think the phenomenon you describe started impacting suburbs much the way City A changes starting in the late 80s. So this trend is not new. The spillover to city A is a function of transportation limits first creating those effects in lower cost City B suburbs (I am not convinced of the role of underwriting on what you describe but rather those price increases inviting all of the excess capital we have).

My second point is that remote working, accelerated by the pandemic, is the next technological leap in transportation. Maybe we will get teleportation or flying cars, but not likely. Remote work allows for even more radical relocation without accepting the negative effects of lowering productivity. Agglomeration just happens in the cloud. If that’s the case, every where becomes City A (or, more specifically a suburb of City B). What we need is to take advantage of those places like Dayton Ohio that have infrastructure, lax land use, and an abundance of ready supply.

I guess my bottom line argument is that land use restrictions aren’t the problem but transportation and the limit of usable city size is the fundamental problem. The answer may not be changing zoning - that could disrupt valuable real estate, overwhelm city infrastructure, and create more congestion - but slowly encouraging more of the migration away from existing places (just like we have for the last century). At some point we will need density and will force people to give up their existing spaces, but looking at the size of our country it won’t be for a long while.

Great series 🚀🚀