Homeownership is down more than you thought.

Homeownership is usually reported with households in the denominator. Under shortage conditions, this leads to bias in the indicator. If a lack of housing units reduces household formation, then homeownership per capita deviates from homeownership per household.

Imagine a hypothetical group of 10 families, each with 2 parents and an adult offspring. If the parents all own homes and the children rent, then, there will be 20 households - 10 households that are homeowner couples and 10 households that are single renters. That’s a 50% homeownership rate. 10 households out of 20.

What if there is a shortage of housing and so all the adult children live at home. Now there are 10 households with three members each that are all homeowners. That’s a 100% homeownership rate.

It is natural to report homeownership this way. If we report it on a per capita basis, then in both scenarios, the homeownership rate is 33% (10 owned homes out of 30 people). That doesn’t quite get it right either. And, if there are cultural changes that aren’t related to housing supply that change household sizes, then the homeownership rate per capita adds its own bias.

John Voorheis, an economist at the Census Bureau, has taken up the mantle of pointing this out on Twitter. It has become a meaningful issue regarding long-term trends in homeownership. My analysis won’t be as detailed and thorough as his, but I think I can outline the basics of the issue.

I was sort of late to the realization that this is an important point. In the past, I have tried to correct homeownership for demographics, by, say, looking at homeownership rates for each age group. But, that doesn’t get at this householder issue.

For instance, by some reports, the percentage of young adults living with their parents has increased from 10% to 22% since 2001. Many of those young adults would be renters in a more amply supplied housing market. But, removing young adult renter households (because they are still a part of their parents’ households) makes the traditional homeownership rate for young adults increase.

Estimating Homeownership per capita in an aging population

To get a feeling for how important this is, I have used (1) total population estimates for each age group along with (2) household estimates for each age group from Census Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) table HH-3 and (3) homeownership and renter estimates by age group from table 12 Household Estimates for the United States, by Age of Householder: 1982 to Present from the Census Housing Vacancies and Homeownership (HVS) report.

From these, for each age group, I can estimate the number of homeowners, renters, and non-heads of household in each year for each age group. The headship rate is the percentage of residents of an age group that are heads of households. The simple relationship is:

Headship rate x homeownership rate = Homeowners per capita

In “Shut Out”, and in other places, I have pointed out that there is a demographic shift in our aggregate homeownership data. Older households tend to be homeowners. So as the average age of the American population has risen, there has been an upward drift in measured homeownership rates.

What I haven’t accounted for in the past is that headship rates have a similar issue. Older residents are more likely to be heads of households. So, as the population has aged, there has been an upward drift in measured headship rates. The headship rate is a Simpson’s paradox. The long-term change in the headship rate of every individual age group is lower than change in the aggregate headship rate.

So, let’s get to the charts.

Figure 1 shows the aggregate homeownership rate and the homeownership rate of different age groups. It is easy to get a quick visual of the long-term demographic shift by simply comparing the aggregate homeownership rate to the homeownership rate of the 35-44 age group. Homeownership within that age group has declined by about 8% since 1982 while the measured aggregate homeownership rate has been level over that period.

But, that’s only part of the story. There is also headship and household size. First, I need to digress to an issue I’ve written about before. From the 1960s to the 1990s, the average household size declined from about 3.3 to about 2.6 persons. That levelled out, and today it’s still about 2.5 persons.

One important reason that it levelled out is that there is a housing shortage. Household size can’t decline if there aren’t houses for smaller households to move into.

But, since household size has been level for 30 years, it is commonly treated as if stable household size is a state of nature - a natural stable number we can benchmark to. This is one of the problems that people run into when they try to use new homes per capita or new homes per household to confirm if there is a supply problem.

What if, with ample housing, household size would have continued to decline?

This relates to the headship rate. In other words, headship rates increased from the 1960s to the 1990s - for each head of household, there had been 2.3 non-heads in the 1960s and there were only 1.6 non-heads by the 1990s.

That decline was almost entirely the result of fewer children per household. The average number of adults per household has been pretty close to about 2 members since the 1970s. But, like homeownership, that stability was a mirage. Since 1990, and especially since 2005, headship rates within each age group have been declining. The stable adult headship rate (and household size) was due to the aging of the population into older age groups that tend to have higher headship rates.

Household size hasn’t been stable since the 1990s. For any given household with a head of household that is 34 years old, or 53 years old, or what have you, there are more adults in that household, on average, than there were 30 or 40 years ago.

So, not only is it wrong to assume the stationary mean of household size over time is a state of nature; it’s wrong to think that household size has been stable. In fact, after declining in the mid-20th century, the trend reversed and now the average number of adults per household is increasing.

To try to adjust for this, in Figure 2, I have estimated what the homeownership rate and homeowners per capita would have been since 1982 if each age group had been the same size for the entire period as it was in 2022.

The standard homeownership rate is in the left panel (homeowners per household). The black line is the published homeownership rate. The red line is the homeownership rate with fixed age demographics.

By the way, this is another example of a false sense of stability. Demand-focused analysts can look at the normal homeownership measure and it looks convincingly like there is a stable 64% of households who are qualified to be homeowners. Then, from 1995 to 2004, an additional 4% of households took on mortgages they couldn’t handle. Then, inevitably, they defaulted and lost their homes. And, by 2016, the homeownership rate was back to the reasonable 64% level.

It’s unfortunate that this notion is carved in stone in many analysts’ presumptions about housing markets. I think this is a qualitative belief that serves to greatly increase confidence in various demand-side explanations of housing market trends. It’s all a mirage.

When you adjust for the aging population, the homeownership rate was only about 2% or 3% higher in 2004 than it had been in the early 1980s. And, in fact, if you look at Figure 1, no working-age age group was higher than it had been in the early 1980s. Even that 2-3% increase was due to rising homeownership rates among 65+ year-olds. (And a little bit among 20-24 year-olds, which doesn’t amount to much because there aren’t many 20-24 year-old heads-of-household.)

And, in fact, when we account for demographics and headship, total homeownership peaked at about the same rate in 2004 as it had been in 1982. This is in the right panel of Figure 2. (Remember, homeownership rate x headship rate = homeowners per capita.)

Before accounting for demographics, there is a somewhat similar pattern in level homeownership per capita as there is in homeownership per household, with a temporary bump in the 2000s, which then returned to the normal level. After setting age group size to the 2022 proportions, homeownership per capita actually looks flat from 1982 to 2004 (with a small dip in the 1990s) which then declined to unprecedented lows.

Putting it all together, since 2016 the reported homeownership rate has risen from 63.4% to 65.8%, which is higher than the 20th century standard. But, with fixed age demographics, the percentage of adults who own homes had been about 38% in both 1982 and 2004. By 2016, it had fallen to 33.4%, and it remains at 33.8%. There hasn’t really been a recovery in homeownership.

Homeownership and headship over time

What’s happened? The intense shortage of housing since 2008 has reduced headship. There is a bit of a difference between the age groups who were free-and-clear homeowners during the 2008 crisis, who were mortgaged homeowners, and who weren’t homeowners yet.

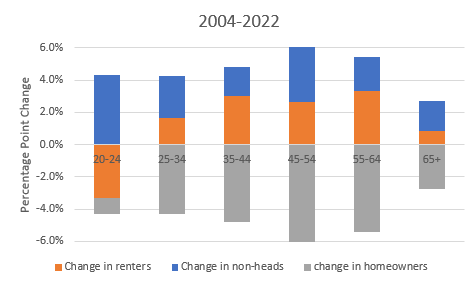

Figure 3 compares the percentage point change in renters, homeowners, and non-heads of households from 2004 to 2022. There hasn’t been much of a decline in homeownership among 65+ year-olds because many of them had a small or no mortgage in 2008. But, the number of owned homes among 65+ year-olds is down a bit over 2%. On net, a few of those former homeowners are renters. Most are not heads of households.

The hit to homeownership was the worst among middle-aged households, who tended to be mortgaged homeowners during the crisis. The percentage of homeowners among 45-54 year-olds has declined about 6% since 2004. On net, about half are renters and half are no longer heads of households. (Of course, there are countless moves between the 3 categories, and these are net numbers.)

Among 20-24 year-olds, who weren’t adults during the financial crisis, the supply shortage is the key issue, and so there has been a 4% drop in the number of heads of households. Instead, they have roommates, or they live with their parents, etc. And the number of both renters and owners has declined.

For 25-34 year-olds, the pattern is a mixture. Homeownership is lower. That is mostly reflected in a larger number of non-household heads, but there also has been a small increase in renters.

Adjusting for age demographics, Figure 4 shows the trends over time. The number of adults who are not heads of households has been rising since the early 1990s. That’s about when I would track the current intensive shortage of housing to. That’s when rent inflation started to be permanently higher than general inflation. It’s when the growth of real housing consumption started to perennial track below the growth of other real consumption.

From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, there was a bit of a boost to homeownership. So, from 1982 to 1994, basically, holding age demographics constant, there were 2% fewer households. On net, 2% of adults changed from being a homeowner to being a roommate.

Then, from 1994 to 2004, 2% of adults went from being renters to being homeowners. Then, from 2004 to 2016, 4% of adults ceased being homeowners and became renters. Finally, from 2016 to 2022, 2% of adults shifted from being renters to being roommates.

What looks like a return to rising homeownership since 2016 is not a rise in homeownership trends at all. Half of it is just an aging population. Half of it is a decline in renters. The numerator of the rate of homeownership hasn’t increased. The denominator decreased.

Figure 5 shows homeownership per capita by age group since 1982. The aggregate rate has been pretty flat. But it’s only flat because there are more older residents. Homeowners per capita for all the working-age age groups have declined by about 5% or more since 1982, and, on net, that is from declining households rather than from rising numbers of renters.

Where do we go from here?

Fixing the mortgage regulations that pushed homeownership below the long-standing norm isn’t on anyone’s radar. As far as I can tell, it could be fixed within the federal agencies without any say-so from Congress. Congress probably wouldn’t even notice. It would be the easiest thing to do. But nobody in a position to do it has any inclination what the problem is.

It does, however, look like housing construction will continue to recover. Finally, it might be possible for household formation to increase again. But, it won’t come from new homeownership. It will come from an increase in completions of apartments and of single-family homes built for rent.

So, the trend in household formation will reverse if there is a building boom. Roommates might start to become renters. And, the age demographic bias may be declining. The median age of American households had risen pretty linearly from the early 1990s to 2020, but it has flattened out in the last few years.

If we have a building boom without a mortgage market correction, then I don’t expect to see the published homeownership rate rise substantially. The new households will tend to be renters. They shouldn’t be. But they will, unless someone who can do something about it notices.

But, in any case, moving from roommate to renter will be a welcomed change for many Americans.

A lot to unpack here, and thanks for taking the deep dive. I feel like the U.S. is in the midst of a gruesome social experiment: Younger generations delay household formation & ownership and just wait for boomers with large houses to die. While they're waiting, they don't have kids, don't move around the country, and don't have any ambitions except trying to outlast their parents. Given that wealth and political leadership is concentrated in the hands of the older generation, this experiment is being drawn out by lending/land use regulations and the magical medical apparatus that sustains the old people for longer than anyone expected.

Seriously, yes, there have been technological breakthroughs---like i-tablets, better medical procedures and drugs, and so on. Tires last longer, cars may be ugly and cramped but last longer.

Private enterprise continues to better products and services.

But housing is a daily disaster for most Americans, and wages have stagnated for 50 years, and even gone down in real terms for young males.

The racial-social-political tensions appear...well, insoluble, and exacerbated by de facto immigration and trade policies.

For whatever reason, academia and media is teaching people to hate the perceived oppressor class or race, including Jews.

The left-wing of America has been valorizing Muslim terror.

Yes, there was rotten and overt racism and homophobia 50 years ago in the US. And that has improved (but not if you listen to the permanently aggrieved).

Well, good luck to us all.