OK. All three of my recent articles are now posted.

First, my article at Liberal Currents outlined a century of housing policy strangulation that ends with the potential final act of banning mass Wall Street ownership of homes.

Then, my short article at Discourse Magazine focused on that last step, and dug into a little more detail about why it would be so harmful.

Now, my backgrounder on this has been posted as a research brief at the Mercatus Center.

Most economics skeptics are kooks, so I hate to have to wade in those waters, and I hate to sound vain about my project, but this issue of corporate money in housing is one of many examples where economists across schools have simply not accounted for the extreme crackdown in mortgage lending, well into the traditional prime market, after 2008. On things like this, it’s like discussing disease without germ theory. My brief at Mercatus goes into the details of the appropriate narrative of post-2008 housing.

The basic problem is that the crash from 2008 to 2012 was treated as a return toward normalcy. I have written about that before. It led Austrian-style finance and econ folks to call for more liquidationism, even as collapsed markets were well into disastrous disequilibria. It also leads to self-identified working class activists and sociologists who view the post 2012 housing market as some sort of missed opportunity for helping poor residents own cheap homes while being completely ignorant and incurious about the regulatory sledgehammer that was necessary to cut working class real estate valuations down by half or more. To repeat myself, they are like humanitarians who, if they had a time machine, would use it to return to Nagasaki in 1946.

There are some pundits, economists, etc., who recognize the obvious need for a corrective to conventional wisdom, in hindsight. Price trends since 2012 make it increasingly hard to hold onto the view that home prices in 2005 were irrationally high and in 2012 they were closer to normal.

We’re just working our way through another cycle on the orange line in Figure A in housing narrative building. Each time the orange line bottoms at a higher level, there is a fresh battle between the “swing the sledgehammer harder until we’re poor enough to stop spending so much on housing” camp and the “wait, what the hell are we doing?” camp. I would hope that the number of the latter camp can eventually outweigh the motivation of the former camp.

The “sledgehammer” camp won in 2008. We almost beat ourselves so fully into submission to get the orange line down near the blue line, briefly. But that meant that home prices were well below equilibrium.

By that, I mean that, in a generally functional housing market, over time, housing starts ebb and flow over the business cycle, but after 2008, the clamps we put on working class homebuyers were so tight that low tier home prices were pushed far below the price that would induce new construction. It took more than a decade for prices to recover back to an equilibrium where the market is starting to clear again with marginal changes in new supply.

I introduced this issue in one of my earlier Mercatus papers. In a market with elastic local supply conditions, the price of new homes is anchored to the cost of construction. Mortgage access, changing incomes, financing costs, etc., change the yield on housing - or conversely the price/rent ratio. So, as visualized in Figure 10, where price is anchored to construction costs, factors that would increase the price/rent ratio largely cause rents to decline. This is what happened in most cities before 2008.

Figure 11 from that paper highlights the basic framework you have to understand to properly interpret what has happened after 2008. We cut out the working class owner-occupier market that used to set the marginal home price. The demand for shelter has not changed; only the set of buyers allowed to own it has. The only thing that could happen is what did happen - rents had to rise to unprecedented highs in order to pull prices back up to a level that would finally induce new construction.

And since all of us - me and you - through our federal representatives, have cut out most working class or marginal prime borrowers from the set of potential buyers, the only viable source of buyers at scale was Wall Street. Cue the countless popular accounts and academic literature who track the correlation between Wall Street buying and rising prices, and conclude that Wall Street makes home prices go up!

So, if you don’t account for what we did, we seemingly have definitive evidence that Wall Street buyers cause both rents and prices to rise. And, so there is a new, and very large, brigade of sledgehammer swingers who are passionate and convinced that the orange line in the first figure will finally be tamed by the “ban Wall Street landlords” swing.

We have to get in front of this. Our country is falling apart. The human suffering in every public space in the central Phoenix area is a stain on all of us, and I can’t bear to see us keep doing this. We are currently terrible. And we are getting worse every day. But, to stop getting worse, somehow a plurality of pundits, experts, economists, policymakers, and voters have to shed all of those wrong things that they currently know. I don’t know how to help do that except for trying to continue to communicate these issues in my imperfect way, the best that I can, hoping to stop the worst of what we will do together.

The New Mercatus Brief

Here are some select key figures from the new brief.

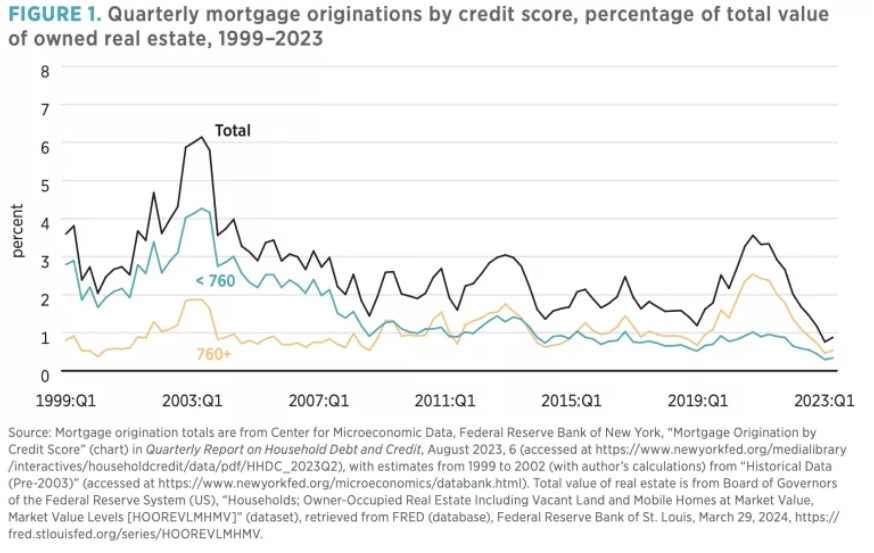

I think Figure 1 can be a useful visualization to help see the basic change in lending standards since 2008. Basically, there was a relatively stable trend before 2008 that, in any given quarter, new mortgages worth between 0.5% and 1% of the total value of owner-occupied homes were originated to borrowers with credit scores above 760. And, between 2%-3% were originated to borrowers with credit scores below 760. This does not seem to have been particularly different during the 2000s than it had been before.

There are 3 periods - around 2003, 2012, and 2021 - where originations spiked during tactical, rate-based refinancing booms occurred. (Unfortunately, the visualization norms of the day require using inexact labels on the x-axis. It is my fault for not trying to push for better labelling on this chart. So, you’ll have to take my word for it that) the spike in borrowing in 2003 was over before the subprime boom happened (2004-2007). So, before 2008, lending to 760+ borrowers was just under 1% and lending to sub-760 borrowers was just over 2% of the total value of the existing stock of homes each quarter. This was pretty normal, even during the subprime boom.

And, you can see that, over the course of 2008, lending to sub-760 borrowers was cut by more than half. It remains that way today. Today, lending to both 760+ and sub-760 borrowers amounts to less than 1% of the total value of existing homes each quarter.

There has been a dearth of buying activity among owner-occupiers that is highly correlated with credit qualifications.

You can see the effect this has had on housing construction.

There is multi-unit construction which had remained cyclically strong right up to September 2008, well after single-family construction had collapsed. And, it recovered back to pre-crisis levels relatively quickly. But, it caps out at about 400,000 units annually because of our urban land use regulation problem.

Before 2008, we compensated for that cap by building a lot of single-family homes. For the decade before 2008, the US averaged about a million and a half new single-family homes annually. New single-family homes have always been almost exclusively an owner-occupier market. So, when we regulated away half of the mortgaged owner-occupier market, that market collapsed. Prices in credit-dependent neighborhoods across the country collapsed, and housing construction of entry level homes also collapsed.

By 2017, the average price of homes across the US had risen back to a level similar to the average price in 2006, which was the last year with sustainable new home sales. Figure 5 highlights how many homes in each year were constructed at various price points.

Since 2008, basically, a half million or more new homes have been missing each year in the affordable/entry-level single-family market because of the mortgage crackdown. The mortgage crackdown hit low-tier prices much more harshly than it hit high-tier prices. What little funding there was for homes in those price ranges could buy existing homes that were much cheaper than builders could construct new homes for. The market was dead. Construction in the high-tier market (homes above $300,000) had fully recovered.

So, we have been stuck at a low level of construction for a decade as the process from Figure 11 above played out. Total new construction per capita has been well below what would have been considered recessionary before 2008. This is when we have developed our 20 million home shortfall. The damage of the mortgage crackdown, together with urban housing regulations, is much greater than the damage that urban housing regulations could have ever caused on their own.

So, we have had a decade of unprecedented rent inflation. This had to happen. Housing supply could not recover until it did. Investors were buying existing homes instead of new homes because existing homes were too cheap. This is the trick of Figure A above. This is the battle between the sledgehammer camp and the “What the hell are we doing?” camp. These trends are not subtle. The poor souls living in our parks are not subtle. The rent inflation in Figure 7 is not subtle. We are a broken economy. And to understand what is happening, your switch has to flip from camp Sledgehammer to camp “What the hell?” You have to come to the counterintuitive view that home prices since 2008 - the orange line in Figure A - have been far too cheap. You have to understand that.

It’s a big leap. It’s a regime shift. You can’t come to that view in baby steps. It has to be a revelation. And you have to be open to it. Many won’t be. And we must defeat them. The victims living in our parks require it of us. And the enemies of this economic healing will be passionate, highly motivated, and self-righteous, in many cases. If they weren’t passionate, they would be able to make that conceptual regime shift. They would be able to see, “We’re on the orange line!”

And, here is where we are. After a decade, rents have finally risen enough to start motivating Wall Street to buy new homes instead of existing homes. This market should not exist! We should be building millions of apartments and millions of single-family homes for owner-occupiers. In a first-best world, those markets would be legal, but they are not. So, if we are bound and gagged, and the best that we can do is crawl, then we must crawl. So, we are crawling like nobody’s business. That’s what we are doing in Figure 8. Lacking a legal pathway for any other form of housing, Wall Street is starting to order up new homes.

I think this single-family build-to-rent market is going to explode faster than almost anyone currently appreciates - because of the timeline that I have laid out above. It is going to explode because we have been in a disequilibrium for a decade, and we have just recently, suddenly, jumped over the tipping point. We are back at an equilibrium. We need millions of homes, and Wall Street can now buy them from builders on favorable terms. The bull has left the stall.

But, this explosion of Wall Street activity is going to prod the Sledgehammer camp - especially the Sledgehammer camp that is highly motivated by their concern that Wall Street pushes rents and prices up. So, just as Wall Street has finally moved the market to a point where more new homes can be constructed and rents and prices can stop rising, the Sledgehammers will be fast and furious.

If it takes a while to turn the boat around, we at least need to avoid accelerating into the shore. That is what will happen if that market gets banned. Our most vulnerable fellow citizens need us to fight this. It may be the most important battle yet.

If you have read this far and there are at least a few neurons in your noggin that are starting to fire up to put down the sledgehammer and join team “What the hell?”, then please watch these trends. You’re going to see a continuation of positive surprises on build-to-rent activity. Please, consider that to be a confirmation of the narrative I have just laid out.

Please, when you hear the backlash start to form, consider that this isn’t a time for baby steps. It’s a time for a regime shift. This is our fourth for fifth best world, but it is the best we can do now, and the continuation of that Wall Street build-to-rent market might literally mean the difference between life and death over the next few years for families currently spending their summers in Phoenix parks.

FYI, several if not all links are broken in your Liberal Currents article.

Kevin,

I’m a young(ish?) father with young children. I never really knew much about what seemed to be the esoteric magic of the housing market before I began reading your work. I’m learning slowly, but learning I am. Would you be willing to check my summary points below to see if I have the timeline / order of events correct?

If I have this right, then:

- Existing were too cheap immediately post-2008 because new regulations suddenly disallowed poorer potential-buyers from qualifying for mortgages.

- Low prices meant less new-home construction at those price points, so the only new homes being built were more expensive ($300k+) because construction companies couldn’t afford to build at a loss. Even as home prices rose, construction companies, due to competition, still couldn’t afford to build lower-cost homes.

- Rents have been rising in response ever since, as those who would be buying starter homes couldn’t but still needed somewhere to live, driving up demand.

- Wall Street (which mostly means housing-related stock prices and investment firms, yes?), which had always invested in real estate, has been buying homes at the too-low prices, which has driven parties to invest in new-home construction (I’m very shaky on this part), which is a bad thing (but why?).

- Recently, the home-price:available stock ratio hit a point of reversal where we could see home prices come down in the coming years. We still haven’t fixed the stifling mortgaging regulations, however, so we might see some drastic, short-sighted move by Sledgehammer Gang that would reverse the reversal.

Sorry this comment is overly long. I hope it wouldn’t be too much effort on your part to respond to one or two Qs I have.

All best—thanks for sharing other places where we can find your work.