Myths of the Housing Bubble, a continuing series

The New Republic recently posted a screed against private market driven homebuilding. It’s mostly just standard prejudicial anti-market stuff from a point of view which is opposed, in principle, to the primary source of affordable housing. You can read it if you want to, I suppose.

The main reason I am citing the article is because it contains a good example of how myths about the 2000s housing boom are a reliable “own-goal” in making housing equitable and functional. Understanding this is an important element in having a clear-eyed view of the pros and cons, and the successes and failures, in housing markets, so that housing stops being an albatross around our economic necks.

There are too many motivated misunderstandings in the article to respond to. For the purposes of this post, I will focus on one key paragraph:

Perhaps the best illustration of elite priorities is the city’s mismanagement of the 2007 foreclosure crisis. When the subprime mortgage market collapsed, Black neighborhoods suffered the bulk of Atlanta’s foreclosures. In 2012, as the market began to recover, the same neighborhoods became “strike zones” for private equity firms. With home values badly damaged, Immergluck argues, the city could have reserved foreclosed properties for long-term affordable housing or sold them to Black households at low prices. Instead, city leaders allowed loan servicers to sell those properties in bulk to Wall Street–backed firms like Blackstone seeking to profit from single-family rentals. The result was “a major transfer of tens of thousands of single-family homes from homeowners, including many families of color, to investors.”

As EHT readers know, the 2007 to 2012 period was universally, overwhelmingly, driven by a deep contraction in middle class mortgage access. Figure 1 is a chart that may show up in one of the papers I’m currently finishing up. These are Case-Shiller high and low-tier home price indexes for Atlanta from 1999 to 2016, with Phoenix and LA included for comparison. These are nominal, not adjusted for inflation or incomes, so there should be a bit of an upward drift.

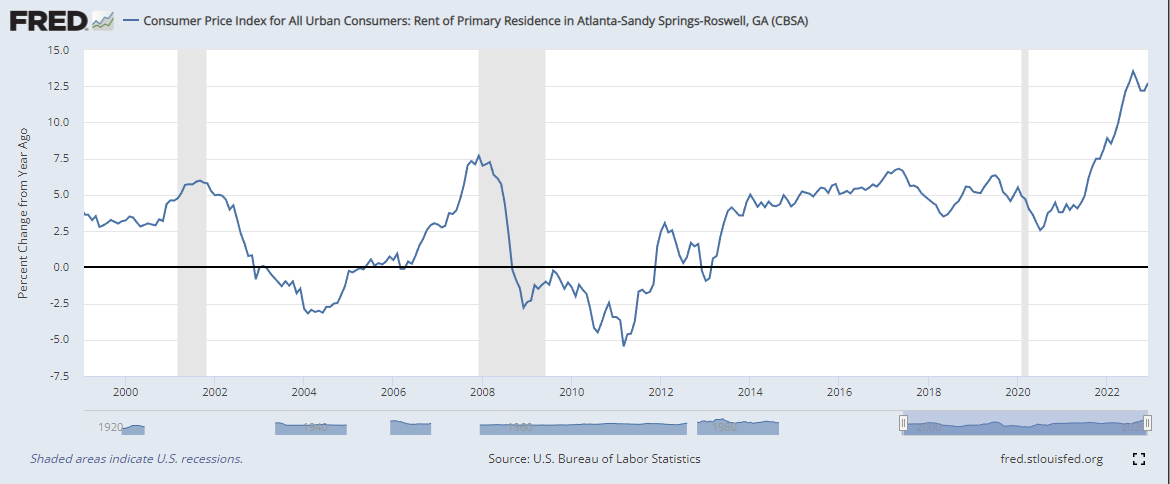

The long and the short of it is, low tier and high tier Atlanta housing moved together until 2007, at very moderate levels, and rents, by the way, in Atlanta were very affordable. In fact, from 2002 to 2006, there was cumulative rent deflation in Atlanta. How much would you like to bet me on whether the author of this article would like to go back to the policies and market norms of 2002 to 2006 when there were declining rents, moderate home prices, and record high rates of homeownership in Atlanta?

This is the problem. 2005 was housing doing the best it could with its hands tied behind its back! It was probably the best, most equitable housing market Atlanta has ever seen. And until we believe that, internalize that, insist on it as an empirical prior, then we might as well argue about the position of Mercury in the sky because whatever you’re trying to do, you won’t be grounded in the empirical world. Until you can do that, you’re dealing charlatans, partisans, and ignoramuses the winning hand in discussions about what is happening.

As long as the truth isn’t an accepted premise in a debate, the debate will be won by the advocate with the most emotionally compelling falsity.

Anyway, I digress. Back to the chart. Low end and high end Atlanta were similarly moderate markets in 2006. Yet, in the bursting of the so-called bubble, it was low end Atlanta that clearly suffered the worst bust. This is nuts. It’s an anomaly. Low end Atlanta in 2012 is something that should jump off of Figure 1 and slap you in the face as grossly wrong.

And, back to their paragraph, what do they have to say about it? “Immergluck argues, the city could have reserved foreclosed properties for long-term affordable housing or sold them to Black households at low prices.” The low prices seem like an opportunity. Why couldn’t the city have arranged to sell the properties at such low prices to the local families?

But, the only way to get such low prices is to make it illegal for those families to buy those homes! Those low prices weren’t an opportunity. They were the symptom of the problem. How exactly would this policy work? First, cut off access to mortgages through the FHA, Fannie & Freddie and threaten any private lender who would dare service that neighborhood. Then, when the lack of local buyers sinks prices 65% from a moderate peak, you put together a city program to sell those same homes to the same people whose exclusion was required to get there?

That ridiculosity is presented as the only obvious solution to the problem. If the point of your project is your concern about trends in Atlanta real estate, and a 65% drop in Atlanta low tier prices seems like just a state of nature we should accept as normalcy, everything you think or say will be ridiculous.

Of course you’re going to be frustrated and unhappy with the market, and full of conspiratorial explanations. It’s like being a bear that wakes up from a tranquilizer dart in a trailer under bright lights. You can’t possibly understand what’s happening around you if this is your state of understanding.

Atlanta’s big problem wasn’t who was allowed to buy houses after 2012. It was who wasn’t allowed to buy them after 2007!

Even if you’re not willing to agree to that, what kind of mutual insanity is this? Why would anyone look back and choose the year 2012 as the point to wish for an intervention in hindsight? Why wouldn’t you want an intervention before prices dropped 65%?!

The necessary first step to not being ridiculous is to step back and consider that, maybe, just maybe, a decline of 65% from prices that had been perfectly normal, was…maybe…a bit of a freaking problem to think about and question for a second or two.

If you’re really concerned about working class Atlanta, you can’t possibly look at Figure 1 from 2007 to 2012 and be unmoved by it, unless you’re under the influence of one hell of a tranquilizer dart. If you’re not looking, first and foremost, for some unusual cause of the Atlanta 2007 to 2012 disaster, then you don’t have any business opining about Atlanta after 2012.

I’m not saying this to cast aspersions. Of course these writers are writing the way they are. That 2007 to 2012 disaster is dissolved into the intellectual waters everyone swims in. In order to be taken seriously, you have to commit to ridiculous observational selectivity. You must choose from the selection of falsities that you are most comfortable with, which allow you to ignore the disaster from 2007 to 2012. It’s not an option to do anything else if you want to be a serious writer for a broad audience.

This is why it is important to correct the conventional wisdom here. Without the obvious truth to draw on, everyone will naturally fall back on their prejudices for the endless debate that can’t possibly be resolved with truths.

And just as I was getting all wound up to type up this post, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution pulled a “hold my beer” on TNR. I saw the AJC article when it was shared on Twitter by Richard Florida.

Again, there is a lot here, but I will limit myself to a single claim related to the topic of this post.

Metro Atlanta home values have risen across the board from 2012 to 2022. But the AJC’s analysis found they climbed more sharply in places where investors bought more houses. In the 30 ZIP codes with the most investor-owned properties, home values appreciated at nearly twice the annual rate as the 30 ZIP codes where investors own the least.

Experts say the effect on homeownership has been dramatic.

A landmark study from Georgia Tech found that the rise in investor activity caused a 1.4 percentage point drop in homeownership rates in metro Atlanta from 2007 to 2016. That translates to 16,500 fewer households owning homes than would be expected, were it not for the influx of Wall Street cash.

African Americans like Lowman have been hit the hardest. Investor purchases explain a 4.2 percentage point drop in Black homeownership during that period, the research found.

Large investor purchases have accelerated since then. During one 12-month stretch beginning in July 2021, investors bought one out of every three homes for sale in metro Atlanta.

In public statements, industry officials deny they are a threat to homeownership, calling it a “myth” that investor activity had priced many Americans out of the housing market.

Tying together a single narrative of investors driving up prices, locking out potential local owners, and lowering local homeownership is the point of the piece, and you can see how it works rhetorically in this excerpt.

Let’s start with the first 2 sentences here. Prices have risen across Atlanta since 2012, and especially where investors have been most active.

Of course that is what happened! Low end Atlanta was on a 65% fire sale in 2012 because investors were the only legal buyers - the result of post 2007 policy choices that none of these writers seems to ever wonder about.

Short of being on the receiving end of a nuclear missile, nothing could have kept low end Atlanta from rising more than high end Atlanta did after 2012. And of course that’s where the investors are.

They do point out, helpfully, that the “landmark study” is based on analysis from 2007 to 2016. From within the conventional fog, those dates may not seem like they mean much, but they mean A LOT! This is a study conducted during a period when home prices were mostly collapsing. It doesn’t belong in a story about investors “pricing out” homeowners.

Here’s a chart with an estimate of Georgia home price/income and the Georgia homeownership rate.

Prices were dropping like a rock when the homeownership rate was falling. And, it is no mystery that the activity of the only type of buyers capable of getting mortgage funding at the time was correlated with the decline in homeownership. Somebody has to own the homes!

The paper attributes this to a causality running from institutional investors to declining home buyers. As far as I can tell, the paper makes no attempt to account for the deep contraction in mortgage access over the period regarding either prices or ownership. Of course, the analysis is cross-sectional, so it would be hard to do that. But, the author doesn’t seem to feel like it is necessary to deal with this problem with the causal interpretation.

Here is a chart from the paper. The investor purchases peaked in 2013. In other words, even in the period cited, greater investor activity was highly correlated with collapsing prices, and investor activity declined once prices bottomed and started to rise again.

Yet, Brian An, Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Finance at Georgia Tech, in the conclusion of a paper in the Journal of Planning Education and Research, concludes, “As such concentrated corporate market power weakens local homeownership, policymakers and planners should consider regulatory approaches for limiting their market share.” And then, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution declares this paper about homeownership in a collapsing market to be a “landmark study” about a market with rising prices and rents.

We keep making various forms of housing and housing funding illegal, and yet, oddly, it doesn’t seem to produce equitably abundant housing. Shocker. The definition of insanity is when you reference that old cliché about doing things over and over again so often that you can’t bear to hear your own thoughts any more.

The thing is, I can understand why he thinks his concerns about investors are so self-evident. I can see why the authors of the other posts and articles here did too. And I can’t imagine any way to encourage them to consider the wrongness of 2012 Atlanta and how that wrongness upsets their apple carts. We are just a very long way from being able to have a discourse based on reality.

This is the struggle we have before us. It is broadly taken as fact that the low-tier market in Atlanta in 2012 was the benchmark after a return to normalcy. In fact, it was the result of the most momentous policy error of our generation. And until that misunderstanding can be bridged, housing debates are all going to be like standing around pissing on each others’ legs and fighting over who to blame for the rain.

Investors come in when regulators artificially create or suppress demand/ supply. Think zoning, zero capital required for European banks on AAA CDS, deductibility of mortgage interest and RE taxes for one group (investors), but not (beyond some point) and (here) denying access to financing (either directly, or via oversight of bank activities).

Investors just jump on opportunities when supply/ demand is regulated up/ down.

Very well said!