A Brief Follow Up to the Brief History

A couple of postscripts to the previous post.

Postscript 1

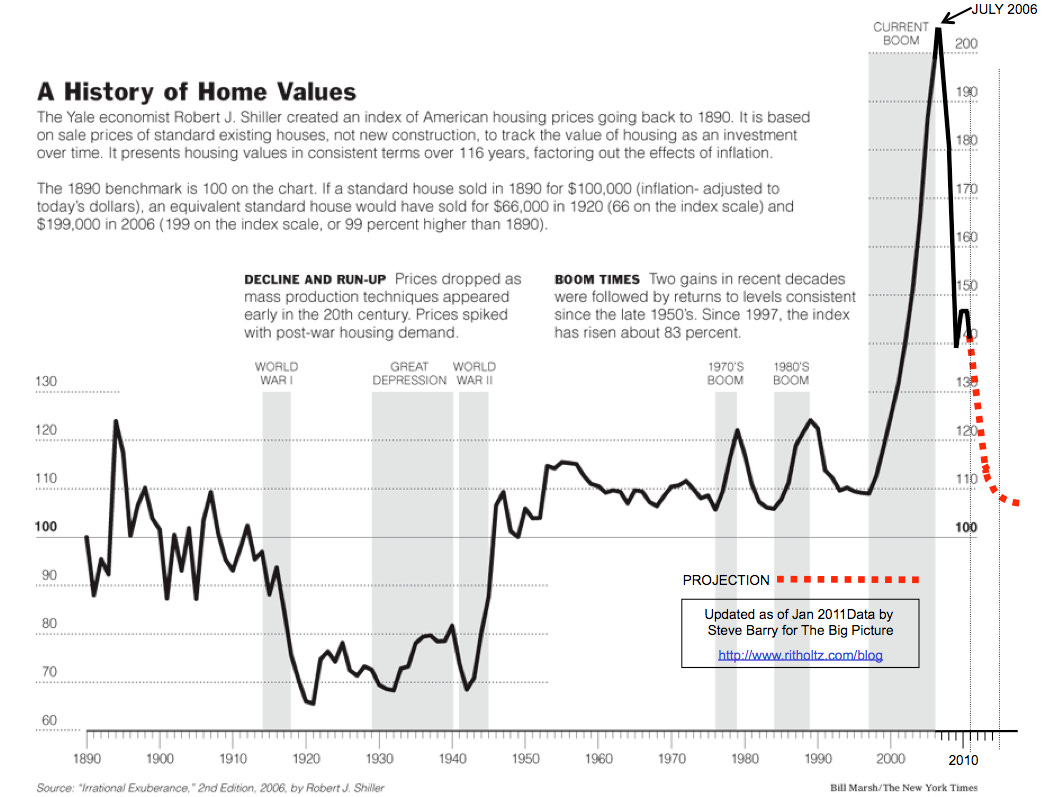

The last version of the New York Times chart of the Case-Shiller index with the red dotted projection line that I can find was posted on April 2011.

Here are high tier and low tier home prices in Atlanta, tracked by Case-Shiller, adjusted for inflation.

I frequently point out that the reason we had a financial crisis and a housing bust is because those were the most popular domestic policy goals of my lifetime. I hope this juxtaposition makes clear that the ridiculousness of that claim is not due to its inaccuracy.

In April 2011, Barry Ritholz was projecting a future contraction in home values as large as anything in US history. You might object that he is an outlier. I would point out that this was about the time that Ben Bernanke was excusing the slow recovery because there was still a glut of homes. Also, I’m not sure you could find a single example of someone making the opposite projection that Ritholz was making. Was anyone - anyone - coming to the defense of working class Atlantans, asking for policy goals that could turn back 60% losses? Property values recovered anyway. Did anyone - I mean literally a single person - overestimate the future price trends in low tier Atlanta?

During TARP, QE, and everything else, did anyone, a single person, object that we weren’t doing enough to raise home prices back up to reasonable levels and stimulate homebuilding?

Postscript 2

This point isn’t directly related to the post, and these are measures I have shared before, but it’s reminiscent of the image of the entire economics profession looking out the windows on the wrong side of the house during the atomic bomb test.

Real housing consumption per capita rose pretty linearly from World War II on. Most of the big zoning changes that motivate YIMBYs happened during that time.

Rents have been rising since the 1970s, generally because of the local land use obstructions. But, until 2008, rising rents in a few stagnant cities didn’t really slow down housing growth. It just changed its location.

That process is painful and unjust, but quantitatively, a home was built somewhere.

The crackdown on mortgages did more damage than all of that zoning and housing opposition ever could. After the median credit score on new mortgages permanently shot up 40 points, rent inflation continued to rise as much as it ever had. But, in addition, immediately, and in stark contrast to the entire American peacetime history, per capita housing consumption flatlined.

This is actually an understatement, because families with capital continued to increase their housing consumption, so families without capital surely have been cutting back significantly in order to maintain the stagnant average.

President Biden has been saying the right things about housing. And the administration has been releasing long lists of policy ideas that will mostly not do much. Meanwhile, the federal government has a great deal of control over mortgage underwriting and could single-handedly reverse the single-largest policy problem that is pushing Americans out of housing.

But all his economists are looking out the back window. It’s not that they are wrong about a policy or an outcome. It’s not that they don’t care.

They don’t even know. The mushroom cloud is rising from the American housing market, and they don’t even know they have their finger on the button.

It’s a new thing we’ve done, and there is nothing in the Spring 1997 volume of the American Economic Review that can help them understand it. There’s no mushroom cloud to see through those windows.

I'm not sure what church door in Phoenix you nail your thesis to--we have some in Boston that haven't been converted to condos yet, but the current mayor is going all-in on inclusionary requirements for developers, so we're doomed.

The mortgage suppression problem post-dates the zoning restriction problem, which makes me wonder if the path out of this is to build enough large-scale rental housing to absorb housing demand and eventually exert corrective pressure on overpriced used homes. That would entail doubling unit starts in the multi-family sector---which is probably beyond production capacity for another decade.