No. Taxpayers didn't bail out Fannie & Freddie

A while ago, I did some forensics on the GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) which I have never gotten around to writing up formally. The long and short of it is that they were never illiquid when they were taken into conservatorship in 2008. They never needed a penny of federal cash to make bond payments, etc. In fact, the taxpayer bailout, when you account for everything, was basically an accounting gimmick.

I’m not saying that anyone explicitly saw it that way or purposefully created fraudulent accounting. I’m saying that in the confusion and the moral certitude of the 2008 mortgage moral panic, the American public and the policymakers who were driving these decisions backed themselves into what was nothing more than an accounting gimmick while sincerely believing that American taxpayers were taking on significant costs to save these institutions.

But, before we get to that, let’s back up a bit. The treatment of the GSEs by the Bush administration was really something. I go over this in “Building from the Ground Up”. Both Fannie and Freddie had accounting scandals in the early 2000s. In fact, those scandals were a big reason why Fannie and Freddie both became less competitive, and lost market share to the private securitizations market that became unstable in 2007.

The accounting scandals were about accounting for unknown credit and interest rate risks. So, there is a lot of room for differences of opinion. You issue a set of mortgages at 5%. How many will default? Will rates change to 7% or 3%? Will borrowers refinance early? A financial intermediary like the GSEs has to make educated guesses about all of these things. They hedge against some risks and the let other risks float. Each quarter, all those prices and assumptions change. Do you record changes immediately? Ignore small changes? Set aside allowances to cover future changes?

There are no good answers to these questions. The SEC report on the settlement with Freddie Mac was titled: “Freddie Mac, Four Former Executives Settle SEC Action Relating to Multi-Billion Dollar Accounting Fraud”. It stated:

The SEC’s complaint alleges that Freddie Mac engaged in a fraudulent scheme that deceived investors about its true performance, profitability, and growth trends. According to the complaint, Freddie Mac misreported its net income in 2000, 2001 and 2002 by 30.5 percent, 23.9 percent and 42.9 percent, respectively.

Notice how it says they “misreported” income. Why use that word? Why not “overstated”? It’s because they claimed that Freddie Mac was keeping its reserves for potential future losses too large! The SEC was accusing them of understating their income and making their operations look worse than they were. As part of the settlement, the SEC forced Freddie Mac to lower various loss estimates and increase its stated net worth by $5 billion. The alleged fraud was making themselves look worse than they were.

You ready for this? Guess when this settlement was announced? September 27, 2007.

You won’t find this detail in “All the Devils Are Here”, “The Big Short”, or “Inside Job”.

On September 27, 2007, the SEC ordered Freddie Mac to claim that they were better capitalized and called them frauds for not doing so earlier.

Similar actions with similar timing and similar demands were made regarding Fannie Mae.

Almost one year later, the federal government - mostly motivated by Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson - on September 7, 2008, decided to push the pendulum hard in the other direction. Now, the government decided that Fannie and Freddie needed to write off billions based on expectations of future losses. Again, much of those losses were just guesses based on expectations of the future. They were forced to assume future losses would be so large that they would basically never recover. (The technical accounting issue regarding this point is that a company that reports losses can claim those losses against future profits, and avoid taxation. Those future potential tax savings are recorded as an asset. The GSEs were forced to write off their tax assets.)

Eventually, uncertainties become reality, and eventually, the GSEs reversed those write offs because their losses ended up being much smaller than federal regulators in 2008 had guessed.

But, by then, the damage was done. They had been declared insolvent and taken into conservatorship.

Keep this in mind. Neither Fannie nor Freddie asked for a federal cash injection. They were blindsided in September 2008. The conservatorship was over the objection of the GSE executives.

Why did they object? Because they were not illiquid. They were still paying off bondholders. They weren’t defaulting on any obligations. We can argue about the appropriate estimates of their net worth. But, they were paying their bills. They had cash.

And, so, this is the oddity about the conservatorship. So much has been made of the bailout made on the backs of taxpayers.

They didn’t want your cash or need your cash. And, in fact, when we gave them cash, there was nothing for them to do with it.

What do you do if you have a bunch of cash that you don’t need? You buy Treasuries with it. You loan it to the government!

So, in late 2008 and 2009, the government invested nearly $200 billion in Fannie and Freddie so that… Fannie and Freddie could loan it right back.

Figure 1 sums up various assets reported in Fannie’s and Freddie’s annual reports that reflect either direct ownership of Treasury securities or other near-cash assets that are substitutes for Treasury securities.

Voila! We “recapitalized” Fannie and Freddie.

Now, as I wrote above, I don’t think anyone planned this out. I think federal officials really believed in 2008 that Fannie and Freddie would take on those losses. And, I doubt that anyone viewed this as a fraudulent accounting scheme to create fake capital. I suspect that the government thought it was doing what it had to do, and probably dozens accountants and asset managers at Fannie and Freddie were faced with the inflow of cash and a bunch of new limits on what they could do with it, and independently did the only thing they could do with it.

So, they received nearly $200 billion in cash and they increased their near-cash holdings (like Treasuries) by the same amount. Eventually, after the crisis had ended, after they reversed a lot of those paper losses, the government demanded large dividends for the 2008 “investment”. So, the GSEs have been in a holding pattern ever since, with this nearly $200 billion (which is categorized as “preferred shares”), and in general, the GSEs have to hand over most of the cash they accumulate above that to the government as dividends.

I don’t think this is a scandal or a conspiracy. I don’t think the elites have been hiding this from you for 16 years. I think we had a moral panic. We were collectively running around hitting ourselves on the forehead with mallets, yelling, “woop, woop, woop”. These are simply questions countless academics and historians were uninterested in because the readers and the public were not interested.

There was a hundred times more concern about inconsequential things like making sure the executives didn’t get paid too much. In September 2008, everybody knew these reckless frauds were in too deep.

The Government Guarantee

It is true that it’s more complicated than that. Would they have remained liquid? I don’t know. Was their liquid status the result of investors who had long expected the government to be a back stop for Fannie and Freddie? It’s certainly a factor.

So, the taxpayer had really had the GSE’s backs long before 2008.

That’s all well and good. But, the point remains. Nobody was ever really taxed $200 billion in order to prop up the GSEs. The taxpayer never really took on any losses for the GSEs, and in fact the government has raked in billions in dividends.

At most, there were some temporary paper losses. Simply confirming that the government would back GSE bonds, in the event of a default, would have probably been enough to avoid panics and keep Fannie and Freddie liquid without pretending to move billions of dollars around.

What is that guarantee worth? As with the 2000s accounting scandals, that is a number that nobody really knows.

But, this is a good example of how the presumptions about the financial crisis seep into every crevice in our conclusions about what happened. The notion that the housing downturn was inevitable is carrying a lot of weight in this story of taxpayer largesse. If the collapse was inevitable, then Fannie and Freddie were just two more reckless institutions that would have died a deserving death if we hadn’t come in to save them.

But, growth at Fannie and Freddie slowed during the boom years from 2004 to 2006. You can see that in Figure 2, which tracks mortgages outstanding at Fannie Mae, by FICO score. The GSEs and the FHA were countercyclical. They weren’t very active during the heady boom years and they came in and formed a mortgage backstop after 2007.

But, that backstop was very selective. The federal government put a lot of pressure on them to tighten up over the course of 2008. Figure 2 showed nominal mortgages outstanding. Figure 3 shows the proportion of mortgages outstanding at Fannie Mae, by FICO score. Mortgages to borrowers with FICO scores above 740 only accounted for about 1/3 of Fannie business before 2008. Then, suddenly, they cut off lending to lower scores. Today, borrowers with scores above 740 account for 2/3 of Fannie business.

This is an important part of the Erdmann Housing Tracker data. That change in lending standards was extreme, and I track the effect it had on home prices after 2007. The entire $5 trillion net loss in American residential real estate was due to credit tightening, which by September 2008 was directly controlled by the government.

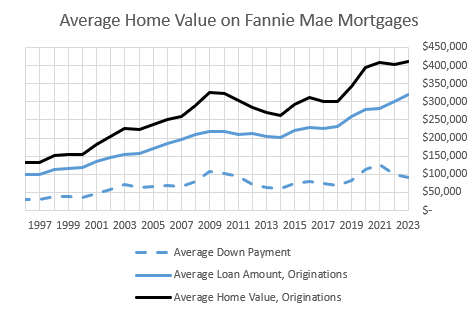

In Figure 4, you can see that from 2007 to 2009, homes in general lost about 20% in value, but Fannie Mae was only lending to homes with much higher values. Before 2008, the average value of homes with old Fannie Mae mortgages was about the same as the average value of homes with new Fannie Mae mortgages. They greatly changed the composition of the market they served.

The government crackdown on the GSEs was the reason for the loss of collateral value. The change in lending standards was the reason the GSEs had to take those paper losses in 2008 that brought them into conservatorship.

In Figure 5, I also show the average down payment and loan size. You can see that at the same time that the average value of the homes they were lending on increased, they also were receiving larger down payments. (The spike in home values in 2020 was also associated with larger down payments rather than larger loans.)

The federal government wasn’t their savior. It was their killer. It was our killer. We were our killer. Mallets. Foreheads. “Woop! Woop! Woop!”

There is a whole, complicated web of facts around this. Some people, to whom I am eternally grateful, have dug around in those facts, in my books and my papers, and found them compelling. I understand that it is a hard sell.

The average home lost about 20% of its value from 2007 to 2011. But, as the tracker data shows, that is highly income dependent. Rich neighborhoods basically were stable. Poor neighborhoods were more likely to lose 40%.

The neighborhoods where buyers could still get GSE loans were stable. The neighborhoods where they couldn’t lost 40%. A loss of 40% on a defaulted mortgage adds up to a lot of credit losses at Fannie and Freddie.

And, yet, even with those massive losses in collateral, the GSEs recovered. They reversed billions of dollars in credit loss reserves. They paid the federal government billions in dividends.

We thought we killed them, but they were only mostly dead. Frankly, it’s an incredible success story. These are hardy institutions. To this day, the modal American passionately defends the destruction of their collateral base, yet they survived.

If only we could let them work again for a majority of American families.

If Kevin Erdmann is going to write insightfully and reasonably about housing and mortgage issues, how does he ever expect to find an audience?

Well, this got interesting. If Kling is right and Kevin is wrong, does that even matter at this point? There are still a few lonely souls who are claiming that we still have a housing bubble in terms of prices and quantity of supply, but the dominant condition in most cities is one of scarcity caused by a confluence of bad regulatory conditions linked to zoning & mortgage lending.

I'll skip work and meals today and just sit here hitting refresh until Kevin responds to Kling.