Hsieh, Moretti, Shiller, and the Rest: Part 1

Productivity and Agglomeration Economies

Recently, there has been a bit of a dust up about the popular urban housing paper from Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation. They quantify the cost of urban land use regulations to aggregate American incomes. In a new paper, Brian Greaney from the University of Washington, claims that the paper’s main findings do not replicate.

Previously, Bryan Caplan had found a simple mathematical error in favor of a larger effect. Hsieh and Moretti had claimed that deregulating land use in a few large cities would had led to 9% higher American GDP over the course of 45 years. Caplan found that, with the error corrected, it was 36%.

The new paper claims that, upon further review, the methods in the paper are inconclusive. Caplan shares Hsieh’s comments here. And, he shares Greaney’s comments here.

This all gets a bit deep in the mathematical weeds. My Mercatus colleague, Salim Furth, does a really good job of distilling the issues here. He also notes that the models they are using include assumptions that are naturally calibrated to produce results of a relatively small scale.

The focus of these papers is agglomeration economies - the tendency for workers to be more productive in dense urban centers. So, the gains from deregulated land use come from allowing workers to move to where their skills are more useful and their wages are higher.

Furth mentions a more thorough paper on the matter from Gilles Duranton and Diego Puga, titled “Urban Growth and Its Aggregate Implications”. Furth’s piece is thought provoking. Thinking through these papers entices one with many questions about the relative value of location and migration, the balance of positive and negative externalities that come from dense urban living, the balance between productivity, wages, costs, frictions like commuting times, etc.

There is a lot to think about here, and Furth notes that some of the factors in these models appear to have reasonable empirical estimates. But, with such complexities, a lot of this analysis gets pretty deep into spherical cow territory.

I am not the person to settle the discussion on the construction of the PhD level models. But, that isn’t going to keep me off my high horse.

All of this goes back to a point readers have probably seen me assert many times. I think that economists have been lured into debating a very complicated, possibly indeterminate issue that is not the most important cost of urban land regulations. Agglomeration economies and urban productivity might not even be the core issue at work here.

First, let me start with a hypothetical - my own spherical cow. Let’s say we have 2 cities. Both have unregulated housing markets and an equal distribution of incomes. Population grows from deaths and births by about 1% annually and so the housing stock expands by about 1% annually in both cities.

Families tend to spend a relatively stable portion of incomes on housing, adjusting real consumption to maintain stable nominal expenditures. In other words, depending on whether they are rich or poor, living in 1920 or 1970, living on the prairie or in Manhattan, they might live in a 500 square foot home or a 5,000 square foot home, with an outhouse or central air conditioning. In the past, in many of those cases, it was typical for families to live in homes that were worth 3 or 4 times their incomes.

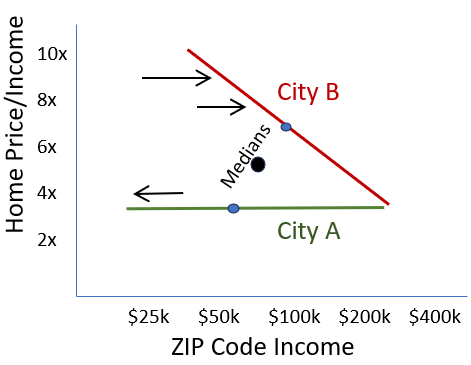

So, in both of these cities, the average home sells for about 3 to 4 times the income of the family living in it, regardless of that family’s income. (It’s a little more complicated than that, but it really is the case that when housing was amply supplied, home price/income multiples across most cities looked, more or less, like Figure 1.)

Now. Let’s just change one thing. Everything is the same in both cities. Population. Productivity. Cost of living. Weather. But, let’s say City B puts a moratorium on new housing. What’s going to happen?

Well, soon, 1% of the population of City B will find themselves lacking satisfactory housing. City A will be an alternative. Some of the new 1% of households with high incomes will just choose to move to City A. City A will permit a new house, similar to the house they previously would have lived in in City B.

But, moving has its costs. The place where we live and where we have set down roots has value. So, some of those households will pay a bit more for slightly less satisfactory housing in City B that is currently claimed by another family in a neighborhood where incomes have been lower.

Now, that neighborhood will have that family, in addition to the 1% of new households lacking additional housing, and those families will make the same decision - either moving to City A or compromising down in City B by paying an inflated price for a worse home than City A would have offered.

Figure 2 reflects this process after some period of time.

In neighborhoods with lower incomes, this wave of unmet demand builds as families with higher incomes make that calculus - move or pay more. And, some portion of them choose to pay more, increasing demand for housing in neighborhoods where incomes had previously been low. That means that the price families with low incomes must pay to remain in City B rises the most, and more of them must choose to move to City A.

As long as City A continues with an unregulated market, there are 2 basic facts driving this model of housing consumption.

The population of City A will now rise by 2% annually instead of 1%. Regardless of how expensive houses in City B become, the population of City A will have to rise to accommodate all the new residents. This is a result fixed by the specifications of the model. The one independent variable here is the change in homebuilding in City B.

The price of homes in City B will settle at the equilibrium where the inflated price of a less desirable home is equal to the cost of regional displacement. This is an idiosyncratic cost, family by family, but those idiosyncrasies add up to systematic price trends. By construction of the hypothetical, that is the only process determining the settled price. City B hasn’t become more productive. There’s nothing special or super about it.

Figure 3 shows the inevitable end result of this process. The migration from City B to City A will lower the average incomes of families now living in City A and raise the average incomes of families living in City B. The average income for the combined population will remain the same, but the average home price will rise.

Doesn’t that look like the US?

Now, looking upon these developments, one could note that City B has higher wages, that the workers there tend to have more valued skills than the workers in City A. If you have an agglomeration model, the Sirens on that model will be bellowing confirmation. There will be countless difficult questions to answer. Did the migrants become less productive when they moved to City A? Does the positive wage available in City B reflect more positives than the high costs reflect negatives?

All of these questions would naturally attract curiosity, even though, as this hypothetical’s creator, I determined that none of those factors are causal. At best, they reflect second order outcomes caused by the housing moratorium in City B.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that agglomeration economies and variable productivity are not relevant in the world we live in. They very well could be. But, perhaps urban economists should take a break from re-estimating their 20 control variables on their agglomeration models to consider that the key data trends that have motivated those studies - excessive housing costs that are positively correlated with incomes and negatively correlated with population growth (at the metro area level) - could exist with no agglomeration economies at all.

Maybe the debate over Hsieh and Moretti’s coefficients won’t be settled by adjusting the model or re-calibrating the control variables. Maybe the debate is hard to settle because the debate is reaching around the primary cost of urban land regulations to get at some tertiary factors. Maybe those factors are harder to quantify because they are tertiary second and third order issues.

In the hypothetical, ignoring second order effects, everything is the same. Productivity is the same. Incomes are the same. The cost of new things are the same. There is no inflation on new production in the hypothetical. The only things that are more expensive are old homes that are resold in the existing home market! New homes in City A cost the same as new homes always have. City B doesn’t have new homes.

Ironically, then, cross-sectionally, City B will appear to be the source of rising wages. However, average real wages for the combined economy will be lower. And they will be lower entirely because the rising rents on the old homes that were already built before Figure 2 was even a twinkle in our eyes will be measured as inflation, lowering real wages.

Also, since the migrants from City B to City A have below average incomes, the extra 1% of housing built in City A will be below average housing, to match those incomes. In the meantime, the remainers in City B will have reduced the housing they use. The moratorium means that the remainers pay more and get less.

So, there are 2 sources of lower real incomes, but in both cases they come from a group (remainers in City B) that has higher than average incomes, cross-sectionally. First, they actually consume less housing, since part of the compromise was trading down. Less is actually produced. (This would lead to second order effects. Less than 1% of City B will need to move, since remaining families will use less housing, and new housing in City A will not need to rise quite to 2%.) Secondly, they spend more for that housing.

The hypothetical conceptually matches the United States. Real consumption of housing is cumulatively 20% below real consumption of other goods and services (black in figure 4). In spite of this, excess rent inflation has accumulated to 60% (blue in figure 4). This has increased the aggregate consumer price level by more than 10% (red in figure 4), which lowers real wages.

The inflationary portion does not lower aggregate incomes. It’s just a fee to the troll under the bridge. That’s income for the troll. A transfer from producers to owners, from wages to rental income. So, consumer inflation is higher than producer inflation and rents are a larger portion of GDP or incomes over time.

Consumer-specific price inflation has accumulated to 30% more than than the GDP price index (red in figure 5). Rent/GDP has risen by 20% in spite of compromises into less valuable units in “City B” (blue in figure 5).

This is the headline story. This should be the keynote speaker, the panel discussion in the ballroom, the graphic on the front page of the program.

All the discussions about agglomeration economies and the effect that migration has on productivity do belong at the conference - among a handful of nerds in a smelly little conference room down at the end of the hall.

But, maybe even my basic indicators aren’t definitive. What does it add up to, in the aggregate?

The decline in real housing expenditures doesn’t necessarily equate to a decline in total production. The City B residents that used to produce new houses now produce houses in City A or they produce something other than houses. Accounting for second-order effects, something is getting produced. (Edited: I originally had the cities reversed here. Sorry for the confusion.)

The decline in real incomes that comes from inflation is just a transfer from workers to owners.

So, my simple yet extreme story may not end up being that different than Hsieh and Moretti’s story. The economy is such that, when you add up all the actions and reactions, any particular scarcity approximates to nothing. And, in my hypothetical cities, if the residents didn’t have a preference to remain, then it would literally amount to nothing. The entire marginal 1% of City B would just move to City A each year. No muss. No fuss. No inflation. No compromise in housing consumption.

And, in fact, for those who move, that is the story. They land in City A with wages and housing costs that are similar to what they would have been in the starting condition of City B. Eventually, when City B becomes expensive, the financial condition of migrants surely actually improves greatly, upon moving. They go from spending extravagantly on the endowment value of place and stability in City B, to spending a regular amount on goods and services in City A. I contend that the entirety of statistical evidence on all these matters is a reflection of City B households paying for ephemeral things that households have never had to, and shouldn’t have to, pay for.

These are difficult questions to answer and difficult values to quantify. As Adam Smith commiserated, “There is a great deal of ruin in a nation.” After all, scarcity is a state of nature. You can say that artificial scarcity is bad even if scarcity naturally exists, but detailing which is which and how much it costs us is difficult business.

To get to the important core of the issue, though, this needs to be a study about economic rents rather than a story about productivity. And, it doesn’t really matter if some of the “City B’s” at the heart of our real world story happen to plausibly seem to be productive places for some people. These trends can be created with housing obstruction even without added productivity. And, cities that are productive cannot create these trends without housing obstruction. In econ parlance, housing obstruction is sufficient and necessary to create disparate costs in equally productive cities. High productivity is neither sufficient nor necessary to create disparate costs.

Occasionally, in a dark alley, someone is met with an ultimatum. “Give me all your money or I’ll shoot.” There isn’t a GDP category for that. It doesn’t change total production, hours worked, aggregate consumption. How could you even statistically confirm that this was bad? We don’t react to an increase in muggings by elevating the status of dark alleys and studying what makes them so special that people would risk a mugging to walk into them.

A great deal of explanation and throat clearing should be required to put agglomeration economies at the center of these concerns. We shouldn’t presume that agglomeration economies are the motivating factor here. And, I think that it largely has become the central focus of urban economics by presumption, because the signals of obstruction have been mistakenly accepted as proof of agglomeration value.

Thanks for diving into this Kevin. I had never heard the term "spherical cow" before, but I don't get out much these days. Agglomeration studies probably yield better data when they focus on more discrete examples, like a cluster of hotels near a convention center or an industrial park with a half dozen plastics manufacturing companies. Comparisons of cities can be brutally complex once you factor in long timelines that may include wars, cultural changes, environmental changes, etc... I happen to prefer your model because it aligns with our current reality of bad housing policy that has created a negative agglomeration effect across an increasing number of metro regions.

"I am not the person to settle the discussion on the construction of the PhD level models. But, that isn’t going to keep me off my high horse."--KE

As a fellow internet-warrior, I salute you!

It sure looks like high housing costs are putting major dents in the US standard of living.

Interesting true story: Office space rents in downtown Los Angeles have barely budged in 40 years. Even in soggy markets, there was always institutional capital to build new towers, and always city say-so. Every tower builder planned in stealing tenants from other towers, locally or globally.

That could have been the story on housing too.