In the previous post, I compared housing supply and demand Austin, Seattle, and Los Angeles and concluded that Austin was the true superstar, Seattle was a bit of a superstar, though lagging a bit in housing production, and LA was a stinker on housing and really, best described as above average but not extraordinary in terms of demand.

In this post, I am going to apply the same reasoning to the 30 largest metro areas. Really, I am struck, at the end of all of this, by just how simple the arithmetic is on this. Population growth is housing growth, but the causation can go either way. Either housing supply drives population growth or population growth drives housing supply. And, since there is a wide range of population trends across metro areas, but natural rates of population growth from births and deaths are relatively similar, then really, you can say that net migration rates drive housing supply or housing supply drives net migration rates. The first is aspirational the second is distressful.

Figure 1 shows the 19 year rate of housing permits and the 19 year population growth of the 49 largest metro areas. The top right are the cities full of aspiration. The bottom left is a combination of cities where economic distress or stagnation is related to staying and cities where economic distress is related to having to leave.

By the way, you can see here the same thing I mentioned in the previous post. Annually, over this period, the typical city needed to build about 3 homes per thousand residents just to maintain level population. Then, above that, each additional home is generally associated with additional population of between 2.5 and 3 new residents, which is in line with average household size.

My measure of the price/income slope (the relative cost of housing for the poor versus the rich) can distinguish between those two types of cities. Another way to distinguish those cities is that the cities in economic distress or stagnation tend to have normal rates of outmigration but low rates of inmigration. On the other hand, cities that create distress by blocking housing tend to have normal rates of inmigration and high rates of outmigration. So, these two types of cities arrive at a low growth scenario through different paths.

Since this is the case, my price/income slope is correlated with outmigration. The more expensive housing is for families with low incomes, the higher the rate of outmigration. I can quantify this. In a city with relatively benign housing supply constraints, homes in neighborhoods where the average income is $100,000 might sell for 3x resident incomes. In a neighborhood with average income of $36,000, homes might sell for 3.7x incomes.

Now, let’s take that same city, still with price/income ratios of 3x in the richer neighborhood. If homes in the poorer neighborhood sell for 4.7x income, then that city will tend to have unusual outmigration of about 0.38% annually. Price/income ratios in the poor neighborhood of 5.7x will be associated with 0.76% outmigration, etc.

Cities either build homes to accommodate population growth, or prices must rise until someone moves away to make room, and those price increases always hit the poorest the hardest.

So, I estimated the housing-induced outmigration each month based on each metro area’s price/income slope, from the end of 2001 to 2019. This is the number of residents who were displaced in order to make up for a lack of housing. So, each metro area had population growth of a certain amount over those 19 years. And, I estimate the potential growth of each metro area by adding the number of displaced residents to the actual growth rate. This gives us a “potential” growth rate. I would argue that the “superstar” status of a city is proportional to that potential growth rate. How many people would like to live there?

Figure 2 compares the actual population growth and the unmet potential growth of each metro area from 2001 to 2019. They are sorted by “superstarness” - total potential growth.

Austin is the standout. It had the highest potential demand and met almost all of it. You have to go down to spot #8 to get to the first city that is regularly cited as a “superstar” city. The reason Seattle seems like a “superstar” city isn’t that it has particularly high potential demand. It’s that it has a lot of unmet demand. In the urban diamond vs. water paradox, Seattle has made itself into a diamond. And so we notice it.

The other commonly cited “superstars” (New York, LA, San Francisco, and Boston) all had potential demand that was higher than the US average population growth rate, but they are all average or below average for metro areas.

In Figure 3, I have sorted them by “unmet demand”. LA, New York, Seattle, San Diego, and San Francisco, are at the top. And, you can see here that, based on this estimate of potential demand, there was nothing exceptional about any of the cities with a lot of unmet demand, with the arguable exception of Seattle. In other words, the cities with the most unmet demand were not cities that had an exceptionally high amount of demand to meet. It wasn’t high potential demand that tripped them up.

The conclusion is quite clear. The “superstar” nomenclature has been a mistake. There is nothing quantitatively special about these cities. They are not expensive because they are super. They are expensive because they are exclusionary. If any of them approved as many homes as any of the major cities in Texas, there is little reason to expect them to be unaffordable.

To do that all at once would entail a 40% increase in their populations. That seems crazy to do all at once. But about a quarter of the major metro areas did it over 19 years. It is an unexceptional expectation.

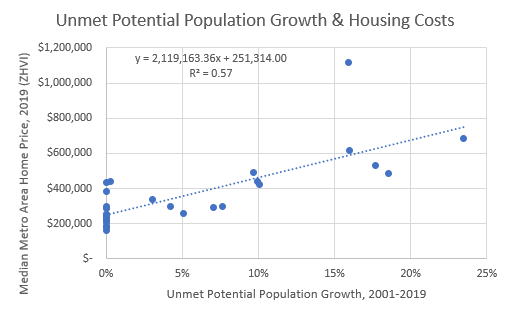

In Figure 4, I show the correlation between potential growth and median home value among these 30 metro areas. There is literally no correlation. High housing costs have nothing to do with a city’s potential.

Figure 5 shows the correlation between unmet potential growth and the median home price. This is entirely a story about constricted supply. It is absolutely not a story about agglomeration economies.

Don’t get me wrong. Agglomeration economies are real. They simply have no important influence on the value of American urban housing.

Here is one way to look at this. Figure 6 shows a ratio of the estimated number of outmigrants displaced by inadequate housing supply relative to the number of new homes built (above the small number required to maintain level population). In Los Angeles and New York City, for every new unit of housing that was constructed (above maintenance level), 5 families were regionally displaced. In Boston, San Diego, and San Francisco, it was about 1 to 1.

Now, the numbers so far have only included the estimate of the number of households forced to move away from the housing deprived cities. There surely are also households that were prevented from moving in. I think this number tends to be lower than the number that are forced to move out. As I wrote in the previous post, in regressions between the price/income slope and migration trends, high housing costs are highly correlated with outmigration but they are not statistically correlated with inmigration. But the causality between inmigration and housing costs is more difficult to tease out.

In Figure 7, I have doubled the estimate of unmet potential. Basically, I am assuming that for every resident that is displaced, there is also a potential new incoming resident that was excluded.

I think that is generally an overestimate. But, here’s the more important point. It would take more displacement than that for these cities to be quantifiably “superstars”. Even with this overestimate of exclusion, they are roughly on par with the affordable cities, like Houston, in terms of potential demand. Even with this overestimate, their estimated potential growth rates were 30% to 50% over 19 years. Nothing “super” about that. And, even at this “above average” but not “super” estimate of potential growth, the ratio of displaced or excluded residents / newly housed residents, would have been 10 to 1 instead of 5 to 1.

The topic of agglomeration economics - this overstated idea among the smart set that cities are so special that building more homes will add to their value and make them more expensive - fails on two levels. First, the cities that supposedly have gained the most agglomeration value over the past 20 years are the cities that didn’t grow much. So, the rise of agglomeration value has not appeared on the margin.

Alternatively, it is possible that the underlying causes of agglomeration value have intensified. Maybe the cities, as they exist, became more value in their static conditions, as urban amenities became more valuable.

But, if that is the case, then the figures above must apply. The cities that had the most potential agglomeration value would lead to an aggregate expression of that value in new demand. Cities that were superstars when agglomeration became valuable would have exceptionally high potential demand. And, the only way for any of the “superstar” cities except for Austin, and to an extent Seattle, to have had exceptionally high potential demand over the past 20 years is if they had created massive exclusion and displacement.

The high property values that have been taken as signals of agglomeration value are first and foremost signals of failure and exclusion. It would have been possible for those cities to discover agglomeration value without creating exclusion and high housing costs, but they didn’t.

When you quantify the exclusion and displacement, the high housing costs are no mystery. At their pitiful rates of homebuilding, there is absolutely no need for a “superstar” explanation for why costs are so high. San Francisco is the only metro area with any substantial unexplained excess in home prices beyond what might be attributed to displacement. In that case, it could well be that the permanent outmigration has reached so far up into middle income families who formerly lived there that there just aren’t many poor families left. The number of residents who don’t move to San Francisco might outnumber the number who had to move away.

But, yet again, any “superness” we assign to San Francisco must be secondary to the primary characteristic, which is displacement and a lack of growth and housing. At most, we could say that San Francisco could have been an Austin. But, the important point is that it is not. It failed to meet its potential.

At the end of everything, it ends up being simple arithmetic. The more “super” you might want to claim these cities are, the more they had to have failed, because, at the end of everything, one central fact dominates their recent histories - they are objectively and decisively outliers on one dimension - deprivation of housing supply and mass displacement.

I will probably continue to hammer away at this until you are tired of it. Much like the myth that the Great Recession was an inevitable result of overbuilding housing, the myth that cities are expensive because they are “superstars” is a brain virus that is doing real damage to American culture and well-being.

Good post, keep them coming. The "superstar city" should be relabeled "static city" per this analysis. What's frustrating is that there are plenty of residents and elected officials in places like Boston, L.A., etc... who are committed to the continuation of this static condition. I'm beginning to think it transcends conventional explanations for NIMBYism like racism and class consciousness. There seems to be an embedded, tribal attitude that can't cope with population growth and the architectural evolution that growth entails. I see this play out at the small town level in New England, where zoning restrictions get pushed to comical extremes--e.g. 10 acre lot sizes. Objections to development of any sort usually get framed as concern over families with school age children driving up property tax rates.

The entire state of Vermont exhibits this collective malaise and has effectively frozen its population at around 600,000 people. Curiously, house prices are considerably below the U.S. median, which can lead to the simple conclusion that it's just another example of rural decline. But when you start to probe the collective zeitgeist of the residents you find many examples of this obsession with preserving the static condition; large lot size minimums, scenic road designations, height limits, agricultural preservation, etc. No politician in the state would dare run on a growth platform.

Very convincing.

BTW, Canada has unaffordable housing now.

Australia, too.

Unless there is a national priority and commitment to housing production, but instead a commitment to boost population and cool wages through immigration, then.....