Does Density Increase Local Prices?

Scott Alexander posted an unusually short (for him) post on the nagging question of whether new supply that increases residential density can actually lower housing costs. He responds to a post from Matthew Yglesias where Yglesias argues:

Many people claim that new construction raises housing prices, either because they are confused or because they believe the demand induced by new amenities swamps the impact of increased supply. This is false, empirically, and in fact, the opposite is true — new construction reduces nearby prices relative to baseline.

Alexander’s response starts with:

The two densest US cities, ie the cities with the greatest housing supply per square kilometer, are New York City and San Francisco. These are also the 1st and 3rd most expensive cities in the US.

The least dense US city, ie the city with the lowest housing supply, isn’t really a well-defined concept. But let’s say for the sake of argument that it’s a giant empty plain in the middle of North Dakota. House prices in giant empty plains in North Dakota are at rock bottom.

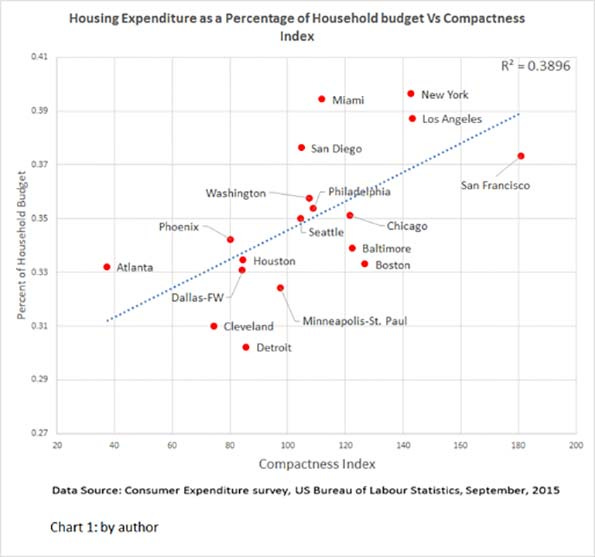

Moving from intuitive thought experiments to real data, we find that indeed, the denser an area, the higher its house prices:

There have been several responses to Alexander. Scott Sumner had a good post.

He mentioned that recent evidence doesn’t really match the agglomeration story, since it is the slowest growing cities that have gotten so expensive. Fast growing cities have generally stayed relatively affordable. One might respond that the charts above suggest that density has gotten more valuable, and so cities that were already more dense have had more demand pressure and price pressure because their pre-existing density has been the draw. But, if that is the case, and it surely is to an extent, we are still left with the aggravating coincidence that the cities with pre-existing density also happen to be the cities that have approved the least housing and have grown the slowest.

Sure, higher density is related to higher costs. But is that the current important factor?

Alexander includes this idealized chart, as a way to think about what would happen if a city built a lot of homes. He writes that considering the patterns above, this seems like an unrealistic expectation.

And he writes:

But doesn’t induced demand violate the economic law of supply and demand? Or doesn’t it (as Yglesias argues) allow an economic perpetual motion machine, where you just keep building houses and generate infinity money as the price of each keeps going up?

No; I think the missing insight is that there’s some pool of geographically mobile Americans1who are looking for new housing (or who might start looking if the right situation presented itself). These people have various combinations of preferences and requirements. One common pattern is to prefer any big city - they would be happy to live in Seattle,orNYC,orthe Bay, if the opportunity came up. Right now, more Americans prefer to live in big cities than there are housing units in big cities, so prices go up and these people can’t afford their dream. As new cities become “big” (by these people’s criteria), they’ll move to those cities, increasing demand. The fact that big cities remain more expensive than small villages suggests that there are many of these people and they’re currently under-served.

So if Oakland became bigger, it would become a more appealing destination for these people at some rate (making it more expensive) and get more supply at some rate (making it less expensive). Since existing big dense cities are all very expensive, most likely in current conditions the first effect would win out, and Oakland would become more expensive. But it can’t do this forever - at some point, it will exhaust the pool of Americans who want to move to big cities (you’ll know this has happened when housing prices are no higher in big cities than anywhere else). So there’s not perpetual motion - just the ability to keep making money as long as there’s pent-up demand, like in every other part of the economy.

And it doesn’t violate laws of supply and demand; if Oakland built more houses, this would lower the price of housing everywhere except Oakland: people who previously planned to move to NYC or SF would move to Oakland instead, lowering NYC/SF demand (and therefore prices). The overall effect would be that nationwide housing prices would go down, just like you would expect. But the decline would be uneven, and one way it would be uneven would be that housing prices in Oakland would go up.

This isn’t an argument against YIMBYism. The effect of building more houses everywhere would be that prices would go down everywhere. But the effect of only building new houses in one city might not be that prices go down in that city.

I think there are several problems here:

First, the correlation between density and cost is positive across metro areas, but it isn’t perfect. The idealized chart basically assumes away the logical claim Alexander claims to be testing. It is possible that density increases costs, and also that more supply would still lower costs, even in dense places. Maybe the cities below the regression lines in the first 2 figures have lower costs because of added supply. It is possible that if you overlaid his idealized chart on the actual scatterplots, it wouldn’t look so crazy after all. If it built a lot, maybe Oakland could be below the regression line, just like half the cities in the scatterplots. And, the first scatterplot has an R-square of 0.74, which is greatly amplified by the 3 California outlier cities. The second scatterplot has an R-square of 0.39. We could imagine a simple model of urban housing economics where density adds cost while supply lowers cost, which explains much of the variance of costs between cities, which reasonable people could agree on, and the question remains, which aspect is more important. The idealized “Oakland” chart doesn’t seem helpful in this regard. His caption on the “Oakland” chart is “Imaginary graph of how price as a function of density would have to look for this argument to make sense.” No. That is an imaginary graph pretending that there is a 100% correlation between density and cost. In fact, “Oakland” is the only realistic plot on that graph. In the scatterplots above, with real values and not just idealized values, there aren’t many dots right on the regression line.

Second, his argument that “The effect of building more houses everywhere would be that prices would go down everywhere. But the effect of only building new houses in one city might not be that prices go down in that city.” is a good starting point. In fact, that’s an important focus of my work. That is absolutely what happens. The most important effect of building new housing in a rich part of town is that it lowers prices in the poor parts of town. But, he’s simultaneously under-applying the idea and stretching it too far.

He’s stretching it too far because cities just don’t draw that much demand from each other. There are cases where supply and demand across cities is related. My whole concept of “Contagion” cities is based on this. It is true that if LA had built more homes in the 2000s, Phoenix would have remained affordable. If the coastal tech centers built more homes today, Austin wouldn’t be struggling to stay affordable. But the causation is clearly in the other direction. These pressures come from displacement due to underbuilding. You could find a positive correlation between high rates of building and these contagion cost pressures, but the families moving to Phoenix in the 2000s weren’t piling into Phoenix because they were drawn to its exciting new commitment for density.

He’s under-applying the idea by removing a lot of important complexities in his mental model. There are, in fact, examples where building can’t help much. New Jersey, for instance, seems to be better about building dense new housing than the New York portions of New York City. Residents substitute all throughout the metro area, so the cost-lowering benefits can’t be fully captured by the cities in New Jersey that have been more friendly to residential development. So, that half of the problem is true. New Jersey can’t make itself an affordable region within New York City by single-handedly building more.

But, there isn’t much evidence at the local level that rents on existing units change much when there is local development. And, let’s say it’s true that new building does cause local costs to rise and costs decline in other places. Every place counts as one “here”, but it counts as an “other place” a lot of times. That’s true of metro areas, municipalities, regional areas, and neighborhoods. At every level, each identifiable unit counts as a single “here” and as a lot of “other place”s. So, we can imagine singular hypotheticals, like “What if Oakland builds but nobody else does.” and there are even a few, sort of, examples in the real world of single areas who don’t get all the cost benefits of building. But, in the big messy world, it isn’t a plausible general rule that individual neighborhoods in Nashville oppose new homes because they think it will just make Memphis more affordable while they get more expensive due to density.

Every place has just been infected with a similar disease, that locals have been given to much power to obstruct change, and the motivations are more simple, banal, and localized.

Is density the same as agglomeration?

But, more importantly and more subtly, I think his basic model of urban demand, described in the second paragraph in the above quote block, is sort of marginally true, such that it is, but it’s not true enough to act as the adequate mental model of how urban housing demand works.

First, there is a lot of sloppiness in general, which Alexander seems to be engaging in here, about “agglomeration” versus “density”. Agglomeration value comes from, among other things, a metro area’s size. But that is just one source. And, eventually, as a metro area grows, it is difficult to keep scaling those benefits without allowing density. So, density is certainly related to agglomeration value. But, at some point, the tendency to treat “agglomeration” and “density” as synonyms strays from empirical reality.

Consider Austin again. It is dealing with growing pains and cost pressures. Incomes in Austin are on the rise. A lot of highly skilled workers are moving there. It is probably the current American poster-child for rate of change in agglomeration value. By Alexander’s story, Austin is growing, becoming dense, and so it has added value that is making its housing costs rise.

But, really, Austin’s growing agglomeration value has very little to do with its density. On the scatterplot above with housing expenditures and compactness, Austin would likely fall somewhere between Seattle and DC and Houston and Dallas. Incomes are high and increasing there, and it is growing fast, but surely we can all see that added density isn’t the cause of these things. Austin is successful, and so it is becoming larger and more dense. That’s the primary causal direction.

Surely Austin will need to become more dense as it gets bigger and richer. And, if it does, it will probably become more expensive. That’s another part of the “agglomeration causes high costs” story that’s a little sloppy. Agglomeration creates value. Supply constraints make homes expensive. As a city gets larger, supply can get somewhat more expensive, but most of the recent change in urban residential costs are in excess of that.

Does higher value cause higher prices?

That’s another area where conceptually one has to be careful. Just because something is more valuable doesn’t mean it will cost more. It’s the water and diamonds paradox. The cost of things has to do with the effort required to make them, or when that effort is impossible or illegal, with scarcity. That has nothing to do with value. Value has to be higher than cost to induce new supply, but beyond that, our lives are ruled by consumption of goods and services whose value is well above their cost. Value can only make a city more expensive if it is paired with exclusion. It is a necessary but not sufficient condition for higher costs.

So, there is some natural inclination for there to be a positive correlation between agglomeration value and density. As we use more oil and must drill deeper, etc., it gets more expensive. But the 1970s inflationary episodes weren’t due to deeper wells. They were due to OPEC political supply obstructions. Both can be at work at the same time, and since the most expensive cities have been the cities with the lowest growth rates, the latter seems most important in the case of housing. In fact, it has gotten so bad that during housing booms and economic expansions, the “agglomeration” cities now tend to lose population.

Are rich inmigrants really the source of high prices?

Part of Alexander’s story is that there is some cosmopolitan group of young professionals that wants to live in an “agglomeration” center. Do we know this is true? Or is this begging the question?

My paper “Price is the Medium Through Which Housing Filters Up or Down” makes a couple related points relevant to this. (1) In cities that become more expensive it isn’t the high income neighborhoods that get more expensive. It’s the neighborhoods with lower incomes. (2) Expensive cities aren’t associated with higher in-migration. They are associated with higher out-migration.

Maybe if San Francisco, LA, and New York City built as many new homes as Kansas City, we would know that they are more popular. They don’t. So supply is clearly a key component to the price problem and higher than average demand is only an assertion.

What is really happening is that, the most expensive cities have below average population growth, and there still is an interior migration pattern within the expensive cities where richer families poach homes in less expensive neighborhoods, and specifically drive up prices where the families with lower incomes live. By the way, Austin, the current poster child of changing and rising agglomeration value, has been getting more expensive recently, but it has been getting more expensive across the board, in rich neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods. That is the pattern I find whenever demand is high in a city that permits a lot of homes. In the most expensive cities, who approve very low numbers of new homes, and who reside at the top right end of Scott Alexander’s scatterplots, the poor put up with the most cost appreciation, and population growth is largely governed by how many of them give up and move away.

You can see this pattern in Figure 1. Where agglomeration and high demand are dominant, it is more expensive for rich families. Where supply constraints are dominant, it is more expensive for poor families.

Do rich residents live in the densest neighborhoods?

Furthermore, the correlation of high earners and expensive homes with density isn’t as strong Alexander’s mental model presumes. Figure 2 compares home values with ZIP code residential density in LA and New York City. In both cases, there is a lot more variance in home values in the densest ZIP codes, but the average home value is about the same in the most dense and least dense parts of the metros.

Now, it is true that the relative value of similar homes is higher in the dense ZIP codes. This shows up in a graph of price/income ratios. The price/income ratios tend to be higher in the densest ZIP codes, as shown in Figure 3. With a given income, residents are willing to spend more on housing in more dense neighborhoods than in less dense neighborhoods. And, as Figure 3 shows, it is the densest ZIP codes that have seen the sharpest increases in prices.

But, as outlined in “Price is the Medium…”, in all cities, with all sorts of density profiles, whenever supply comes up short, it is the poorest neighborhoods where prices go up the most, because short supply leads to a “musical chairs” bidding war for the homes that are there. As Figure 4 shows, the reason prices in the densest ZIP codes have risen the most in LA and New York City is because to a very strong degree, the densest ZIP codes are where the poorest residents live.

Even in 2022, in New York City, the densest neighborhoods are overwhelmingly where New York’s poorest residents live.

Agglomeration value, at most, raises costs on rich residents. Supply constraints raise costs on poor residents.

Figure 5 shows the price/income ratio of homes across Austin and Los Angeles ZIP codes, arranged by income, in 2001 and 2022. Both have agglomeration value. Austin is building a lot of homes, growing, and becoming more dense. LA is not.

I think you can say, in short, Austin is getting more expensive in general because it is getting richer. Los Angeles is getting more expensive because it doesn’t approve adequate housing.

Austin will likely get expensive in a way that correlates positively with density. Austin might be an example of the urban-seeking cosmopolitan story Alexander tells. It would have a lot of the characteristics he is trying to explain at a much smaller scale than the characteristics that show up in LA, New York, and San Francisco. It is pretty easy to tell the two stories apart, once you isolate the symptoms of a supply deprived city - supply deprivation is associated with rising costs on the poorest citizens, very low building rates, high out-migration of the poorest citizens, etc. And, while new homes might gradually cost more in a densifying city, the cost problems in supply deprived cities come from rising rents and price appreciation in older homes, whose original cost of construction is now not particularly relevant to the problem.

Just looking at metro area medians loses all of these distinctions. In fact, I would argue that essentially none of the excess real estate value in the most expensive dense cities comes from agglomeration value. Agglomeration value would mostly flow to consumer surplus. The higher costs don’t come from positive demand. There is positive demand in Austin. The excess costs come from inertia. They come from the preference not to be displaced. They come from the value of locality and community which the non-cosmopolitan locals value, and which prevents them from moving away from cities that are committed to non-growth. The residents of ZIP codes in Los Angeles and New York City are living in neighborhoods where rent takes 50%+ of their incomes for the same reason some families remain in dying towns in places like Appalachia in spite of the lack of local employment opportunities. They value place. And where housing is obstructed, those families have to pay up for every last cent of that value, until they can pay no more and they must move away, which they are by the hundreds of thousands.

Cosmopolitanism isn’t the cause of high housing costs. Quite the opposite.

I'm glad that you and Scott Sumner have done such a thorough analysis of this issue, because it's critical to point out that housing isn't some amazing exception to the law of supply and demand. That we've done such a magnificent job of creating distortions in our housing markets is a consequence of so many dead hand policies that many people believe to be good and wise. The Boston metro region started a war on housing affordability several decades prior to the adoption of any formal zoning codes. These early regulations included prohibitions on building heights, prohibitions on triple deckers, race exclusive neighborhoods, and a strangulation of the power of Boston to expand as a city.

The topic of density is particularly complicated because the gradient distribution for any urban area is so broad that using median levels for any type of analysis is practically worthless. A big part of the fat tail of housing density is the result of wealthy towns that enforce large lot zoning requirements and have set aside massive areas of green space for perpetuity. People value these restrictions, and perversely, "best practice" zoning regulations that date from the 1950's create large lot sizes in relatively dense suburbs that are closer to the urban core. For example, 8,000 s.f. lot size requirements will tend to be the minimum in neighborhoods where most of the lots that were established prior to those rules average 5,000 s.f. or less.

Although I tend to be fixated on the situations in older cities in the New England, the false paradox of "more supply raises prices" could be used in any community that is dealing with a project that alters the scale of their neighborhood in any way. I do wonder about those supertalls in Manhattan, however.

Professor Erdmann,

If I understand this correctly, then an increase in demand for housing leads to either:

1. An increase in housing supply, followed by an increase in rents for wealthier/denser zip codes, or

2. A constrained housing supply, followed by an increase in housing prices in cheaper/less dense zip codes due to speculative activity from real estate investors.

This is a detailed analysis that shows hard work and incredible dedication. However, it still doesn't explain the positive correlation between density and prices.

Why do denser cities face more supply constraints? Why do denser cities face more out-migration instead of in-migration?

Are there long-term, 2nd order effects, related to but separate from the short--term effects that you mentioned in this article? If we went back in time to Manhattan in the 1940s, and stimied any attempts at increasing density in the area, would prices be higher than they are now?

Could the higher costs reflect higher electricity and water prices, and higher taxes that stem from more difficulty in governing the area (i.e. more powerful construction unions, more complex infrastructure)?

Could the higher costs stem from higher costs of living? The landlords and the maintenance staff need to buy food in the local area, after all.

Could the higher costs reflect higher induced demand? You mentioned that demand-increasing agglomeration effects aren't perfectly in sync with density, but if there was even a weak link between the two, then we would still have a positive feedback loop where density increased demand and demand increased density. Even pro-YIMBY neighborhoods will eventually face supply constraints with the local geography; you can't build infinite housing in a finite space.

Your research provides strong evidence for the YIMBY side, but there are still questions that need to be answered before we can call this settled.