"Price is the Medium Through Which Housing Filters Up or Down": Part 2

For Pete's Sake, Unsustainably High Home Prices DO NOT Call For Austerity.

(Part 1: Here)

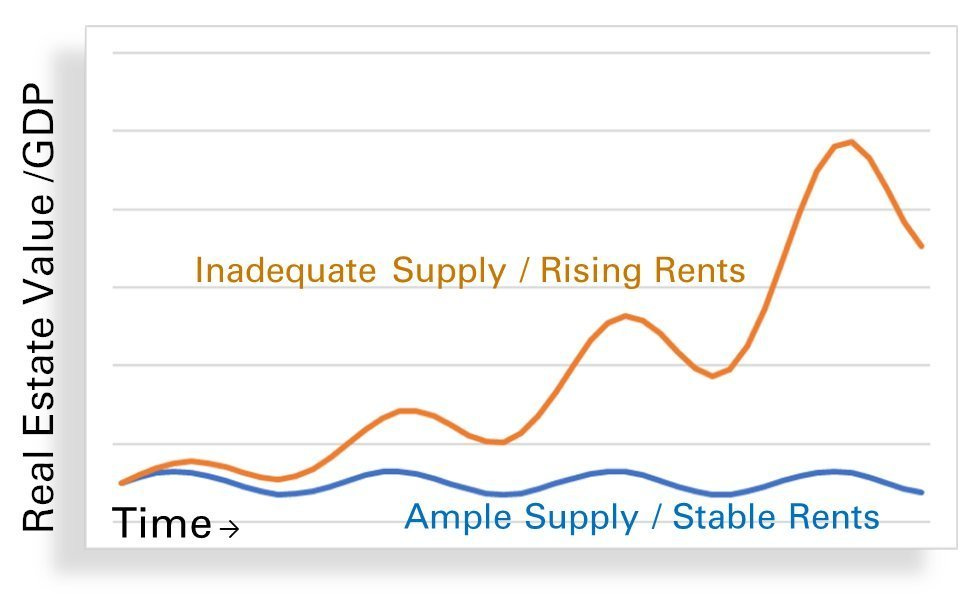

On Twitter, I like to share the “world’s most niche meme”. The figure compares 2 ideal time series which, by construction, have only one difference. One has a stable mean and one has an upward trend. The cyclical impulses are the same.

The point is to show how if you have an asset with a long-term structural issue that leads to an upward trend, in real time, it will feel like a series of increasingly excessive cycles. This is what we have in housing. We have a structural problem that keeps pushing up rents. As housing moves through economic cycles, when a cycle heats up, the problem becomes really noticeable, and there is an outcry to reverse the cycle. The cycle is reversed, and the more out of equilibrium it gets to the downside, the more normal it feels. But, inevitably, the long-term upward secular trend pushes it back up, and the next cycle feels even worse than the previous cycle did. We are somewhere on an upcycle right now, or at least we aren’t at the bottom of one. And, so, many financial pundits, both pro and amateur, are convinced they are witnessing the next in a ridiculous series of housing bubbles, and are almost giddy about watching what they are certain is a coming collapse.

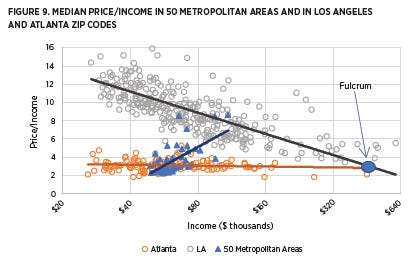

They are wrong. Their eyes deceive them. And, I think using the price/income patterns I highlight in this paper, you can see how the deception might happen. The price/income pattern that is important is the relative cost of housing within each metropolitan area. Where housing is obstructed, the costs fall entirely on families with low incomes. The lower your income, the more financial burden you will feel if your city doesn’t permit enough housing. And, a useful way to measure this is to view home values as a ratio of price/income. The difference between Los Angeles and Atlanta is shown in Figure 2. The only reason the median home in LA is more expensive than the median home in Atlanta is because the median is halfway to poor, and housing costs systematically hit the poor. Looking at medians hides the story. LA isn’t more expensive than Atlanta, in general. The slope of the price/income relationship is steeper in LA. That’s the whole story. You can wage a pretty good guess about how hard it is to build homes (of any type) in a metropolitan area by looking at how hard it is to be poor there.

In the paper, I highlight three recent papers on housing costs, cost of living, and migration.

Rebecca Diamond and Enrico Moretti, “Where Is Standard of Living the Highest? Local Prices and the Geography of Consumption”

Philip Hoxie, Daniel Shoag, and Stan Veuger, “Moving to Density: Half a Century of Housing Costs and Wage Premia from Queens to King Salmon”

D. Card, J. Rothstein, and M. Yi, “Location, Location, Location”

Papers like these are increasingly building our knowledge about how inadequate urban housing is holding back our economy and making it less equitable. Together, these papers describe a broken economy with exclusionary urban centers at its heart. The cities that should have the highest standards of living only offer a moderately high standard of living for high wage earners. And, the standard of living they offer working class families is low. In many cities where gross incomes are high, those incomes are eaten up by housing costs, and the housing costs especially hit working class families.

So, why would working class families move to the high cost cities? On net, they don’t. Why don’t the families that live in the high cost cities move away? On net, they do. But, here’s the thing, and this is an issue where these papers provide a window into what is driving the American housing market. In a world without inertia, inhabited by homo-economicus, you might expect the housing-deprived cities to have a standard of living that is the same as other cities, even though local incomes may be above average. But, you wouldn’t expect their standard of living to be below other cities’. The reason their standard of living can sink below the standard of living in other cities is because people hate to be displaced. People have good reasons to want to remain in their homes and in their home communities. People have endowment effects, and in housing, we consider those endowment effects to be relatively sacred and essential to being human. People are willing to endure a lower cost of living to retain those things. So, they move away from expensive places. They have to, because if there aren’t enough houses, somebody has to move away. But, they must suffer enough to overcome the costs of displacement before they do.

From Hoxie, Shoag, and Veuger:

In 1970 the share of cross-state migrants in high-productivity commuting zones is much greater than the share of cross-state migrants in low-productivity commuting zones. This disparity was mostly driven by non-college workers who migrated towards high-productivity commuting zones with a low share of college workers. This disparity grew smaller over time before inverting entirely. While we do not want to attach aggressively causal interpretations to this exercise, these figures suggest that the elevated cost of housing in high-productivity areas is a particularly important obstacle - and perhaps a proxy for other important obstacles - to spatial mobility.

Figure A.11 shows that cross-state migrants among both college and non-college workers receive housing-inclusive wages that exceed those of non-migrants, to the point where the decline in the urban wage premium is barely apparent even among the non-college workers among them. This highlights that spatial sorting is impacted by moving costs and other frictions in addition to commuting zone wages and housing costs.

Frictions. Few households will migrate into a situation that worsens their finances, so the rate of working class migration into high cost cities is low, but those who do migrate have reasonable standards of living after housing costs. But, households might resist migrating, even if their standard of living is deteriorating where they live. What Figure A-11 seems to say is that incomes after housing costs follow persistent patterns for college educated residents and high school educated migrants. Housing may be taking a larger portion of those incomes, preventing more real income growth in general, limiting more active migration, etc., but at the end of the day, net incomes still follow some sort of normal pattern. But, existing residents with less than college educations don’t follow that pattern. And, the difference between them and others is driven by a handful of outlier metropolitan areas where existing residents are doing very poorly. They are doing poorly because their housing costs are well above the costs that any group of residents, in a world without frictions, endowment effects, etc., would choose.

From my paper:

As technology increases the potential for capital and labor flows, incomes continue to converge geographically, as they have for at least a century. But as a result of inelastic housing supply, it is incomes after housing costs rather than gross incomes that are now converging. The exception is where frictions and inertia push incomes after housing costs lower for residents who do not respond immediately to the forces of housing displacement. High-income households that move aspirationally do not, on average, move to places that will lower their incomes after housing costs. But households with lower incomes that move due to privation from rising housing costs naturally resist moving until the costs are more substantial.

Price/income ratios above 10 in the metropolitan areas with the worst supply constraints, where supply cannot be adequately created through new production, seem to support the idea of recurring housing “bubbles.” Such home prices are surely unsustainably high for the local residents. However, where supply cannot be adequately created through new production, high prices are the mechanism through which those residents will be forced to relent, to finally move away in order to salvage a reasonable living standard, freeing local housing supply for other households. Home prices in supply-constrained metros must become unsustainable to force the migration that allows the existing homes to filter upward. Although this looks like a market repeatedly prone to “bubbles,” it is actually quite the opposite. In a city deprived of adequate residential construction, existing home prices must be unsustainable by some families’ standards.

In an American economic landscape where an important subset of metropolitan areas has binding housing supply, economic expansions are increasingly associated with housing “bubbles.” Policy reactions such as tighter monetary or lending policies have been the primary policy tools applied to pop those putative bubbles. But unless urban housing supply becomes more elastic, the only longterm remedy for unsustainably high home values will be migration. Housing “bubbles” are a form of disequilibrium, but it is not a disequilibrium created by speculative activity moving markets too fast. It is a disequilibrium created by the inertia that slows the migratory response away from cities with inelastic urban housing supply. The significant personal costs of inter-MSA migration are the source of unsustainably high housing prices in supply-constrained MSAs.

For cities like San Francisco, the value of homes isn’t determined by the cost of construction. It is determined by the personal cost of displacement. To put it another way, saying that high costs are causing households to move away may be putting the causality backwards. From 2000 to 2003, a 1.4 percent annual negative net rate of domestic migration from San Francisco was more or less fixed, because the number of homes was relatively fixed. The slope of the price/income line had to steepen until life in San Francisco was unsustainable for 1.4 percent its domestic households. That slope has little to do with measurable things like the cost of lumber. It has to do with ethereal costs like the value of community.

This is not an equilibrium; this is a disequilibrium, and the scale of the disequilibrium is driven by economic conditions that affect migration flows. Again, this is why the housing market appears to perpetually be in some “bubble” state. Housing “bubbles” aren’t driving economic growth. Economic growth increases the pressures of housing disequilibrium, which leads to the appearance of “bubble” conditions. Putative housing bubbles are a reflection of the personal costs that inelastic housing supply imposes on its residents.

Unsustainable housing prices aren’t the result, fundamentally, of overzealous demand. They are the result of resistance to displacement. I would suggest that inertia is a much more plausible explanation for a doubling of real estate values relative to GDP over the past 50 years than stimulus ever could be. The macroeconomic response to those rising values has been to impose recessionary conditions to rein in overzealous demand at the top of each cycle. I fear that the cruelty that has arisen from this pluralism (attempting to solve inequitable local limits on real demand with inequitable national shocks to nominal demand) will be a stumbling block in our communal ability to come to terms with it and reverse it.

I very much appreciate your careful and thoughtful analysis of housing markets. We should call the way migration intensifies competition for positional goods the Fogel Effect, after Robert Fogel’s analysis in “Without Consent or Contract” of the destabilising effects of pre Civil War migration. Also, considering that people value their social connections is something economists can miss, sometimes egregiously, so it is good to see you take it seriously. I discuss an egregious failure here: https://lorenzofromoz.substack.com/p/the-migration-scam