"Price is the Medium Through Which Housing Filters Up or Down": Part 1

Inadequate supply (even "luxury" supply) hurts poor families. Full Stop.

This is the paper that is the formal description of the conceptual framework behind the Erdmann Housing Tracker. The basic idea is that constrained supply does not make homes in a region generally more expensive. It very specifically and systematically makes homes of residents with the lowest incomes more expensive. In short filtering (trickle down, if you will) is the whole game.

I think there are implications here for both local and federal public policy and for macroeconomic financial analysis, extensions and support of the growing literature on filtering and migration, and a tool for use in quantitative analysis of housing markets. That’s too much for one substack post, so I will be discussing various implications of the paper in a series of posts over the next several days.

Part 1:

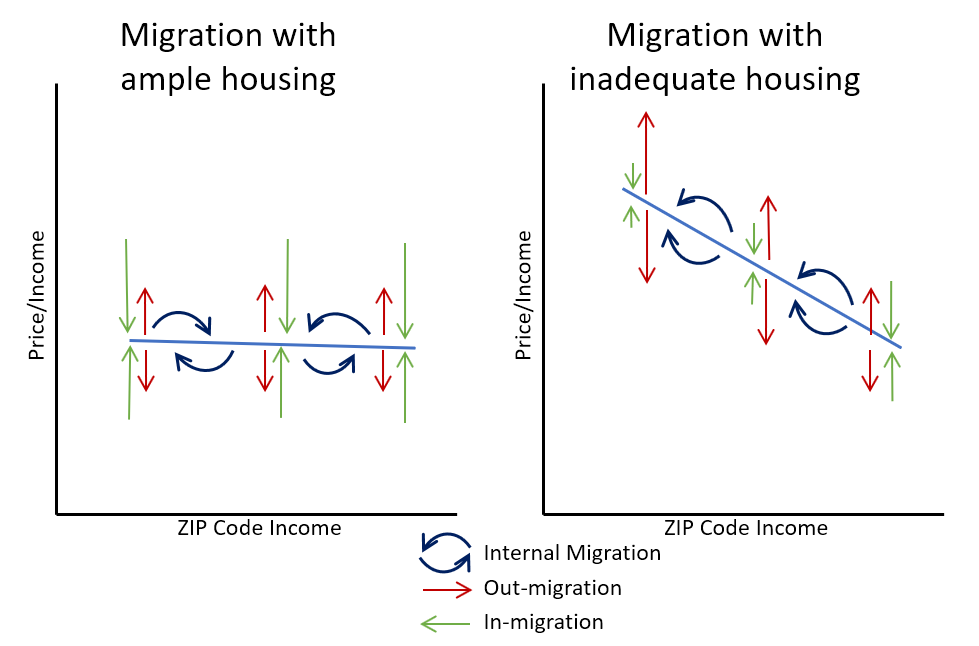

"As supply becomes more and more constrained, the cost of housing in the respectively lower tiers exceeds the norms of metropolitan areas with more elastic supply. As the distance from those norms increases, both the portion of a household’s income that they are willing to spend on housing and the incomes of other potential residents become increasingly important among the factors that determine who continues to live in the metropolitan area.

In a metropolitan area with increasing pressures from residents substituting downward, the price/income level will increase at each lower tier. And as these substitutions become the dominant factor determining local prices, those price pressures will naturally tend toward a systematic, linear function of incomes.

When there is a lack of housing, all of the compromises and substitutions are in one direction - downward. Families with more financial resources have to compromise into neighborhoods and homes that would normally be used by families with lower incomes. That process plays out through price. The families with more resources bid up the cost of homes until families with fewer resources must themselves compromise. Basically, it really is like the existing supply of homes is shrinking. As you move to lower and lower tiers of a metropolitan area’s housing market, the supply shrinks more and more, and the relative price level rises more and more.

At each step down into lower tiers of the market, the supply constraint gets more binding, and it is moderated by several factors. Families that compromise by moving into a house that would otherwise be used by a family of lesser means increase the downward supply pressure in the lower tier. Families that compromise by moving away from the metropolitan area altogether relieve the potential pressure on the lower tiers.

If you think of the demand curve as being populated by various families with different demand elasticity (willingness to pay for housing to stay in a location), there are households at the very left end of the demand curve that will pay very high sums to remain in the city, there are households near the current equilibrium price that have just about had enough and will move with the next rent increase, and there are households to the right of the equilibrium price who are among the millions of families who have already moved away from the housing constrained cities.

The key is that families are self-selecting to move away or to stay within a metropolitan area based on their own idiosyncratic willingness to remain. The answer to the question, “Do you still live in Los Angeles?” is increasingly, “I am willing to suffer more than the others who moved away.” And, that is especially the answer if you don’t have a very high income.

Here is another chart that gets at the same process, which isn’t in the paper but I have posted it previously here at the substack.

When there is persistent outmigration from a city of the families with the lowest incomes, that inter-metropolitan migration is a secondary effect that results from the one-way intra-metropolitan migration which was triggered by housing obstruction.

In other words, in a city with moderate housing costs, a family may weigh various factors—the local idiosyncratic mix of amenities, the social idiosyncrasies of the existing neighbors, aesthetics, proximity to work, and so forth. As housing costs become more binding, the decision of how far down-market to substitute to moderate costs naturally becomes a dominant factor. So as downward substitutions increase (as a metropolitan area’s housing stock filters upward to tenants with higher incomes), both income and the price/income ratio the remaining residents are willing to accept will naturally become more important factors in determining the distribution of housing among a metropolitan area’s residents.

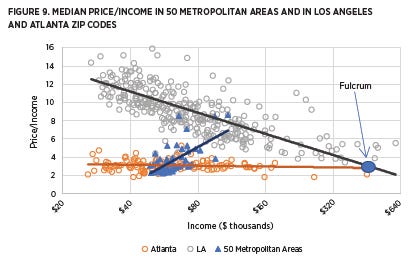

Here is a chart of the type that Erdmann Housing Tracker readers will be familiar with. Inadequate building in Los Angeles doesn’t make housing more expensive in Los Angeles. It makes housing more expensive in Los Angeles for poor families. The reason the relationship shown here is so linear is because the relative incomes of other families who have to compromise into your neighborhood is the primary factor driving home prices, and, family by family, year after year, existing residents must weigh whether they have had enough or whether they will stick it out another year. The slope of that line is a measure of the amount of burden and the persistence of it. The slope of that line is a measure of self-determination under duress. A price/income level of 12 in the poorest ZIP codes of Los Angeles is only possible because it reflects the remaining standouts of a once much larger population, most of which have by now chosen to cry uncle.

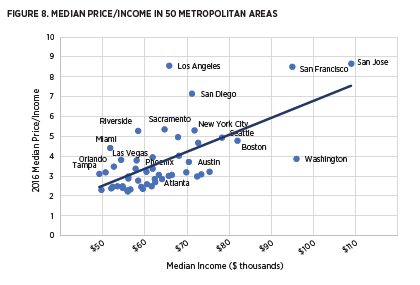

Way back when, when I started studying the 2008 financial crisis, I noticed that there was a weird pattern. The cities where housing costs claimed the largest portions of income were the cities with the highest incomes.

But, it’s even weirder than that. The entirety of that correlation comes from the poorest residents of the richest cities. For the most part, they are the richest cities not because of who arrived, but because of who left. And, it wasn’t just that the poorest residents have left the now-rich cities. It’s that the poorest residents who idiosyncratically rejected high housing costs have moved out of those cities.

That is part one. Stay tuned for more.

Hi Kevin! I thought of a question, and wasn't sure where to ask it, so I'm just writing it on this post.

You've written that when demand outstrips supply, rents rise most rapidly in the lowest income neighborhoods. But when supply outstrips demand, do rents fall most rapidly in the lowest income neighborhoods?

Thank you!