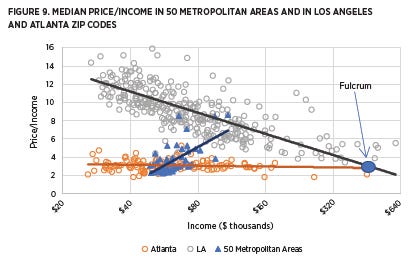

In "Price is the Medium Through Which Housing Filters Up or Down" I walked through a description of the filtering process in an attempt to connect its existence in practice with the price and rent patterns that arise in its absence (or reversal). Those patterns are like this:

Atlanta was a city with downward filtering (Old homes “trickle down” to families with lower incomes over time.) and affordable housing. LA is a city with upward filtering (Old homes are bought by families with higher incomes over time.) and unaffordable housing. Figure 2 is an abstraction of what happens in those two types of cities.

Housing Affordability in an Amply Supplied City

The way I have come to think of a properly housed city with downward filtering is that the cost of housing, when all is said and done, is a function of incomes. There is a level of spending that is comfortable, which households aim for, when supply is ample. Most of the housing stock is old and greatly depreciated. The cost of new construction is only distantly related to the eventual cost of the house 50 or 100 years later. Where housing is amply supplied, residents of a metropolitan area sort into neighborhoods over time that match their household characteristics and preferences, including their income levels. For many homes, there is a significant gray area between their eventual value and their fully depreciated, minimally maintained, “book value”. Where housing is amply supplied, new homes are built, old homes are maintained, and families move and sort between neighborhoods such that everyone can match up with a house that sells for 3-4 times their household income. All those moving parts and marginal investments will adjust to naturally settle at that norm. That could mean the average house is 1,200 square feet or 2,400 square feet. In the past, in many cities, it meant some amount of tenements and boarding houses. It could be an apartment over a store front or a single-family house with a yard. All those types of details depend on time, technology, materials, the size and geography of the city, the location of a unit within the city. Some people will choose old homes. Some will choose new. Etc. Where housing is amply supplied all of those other things will be traded off and changed, until the average home has a value 3-4 times its residents’ income.

Housing Affordability in an Undersupplied City

Whereas the cost of the typical home in an amply supplied city is determined by the income of its residents, the cost of the typical home in an undersupplied city is determined by the income of other residents. This is why some residents of San Francisco have a toxic attitude toward tech workers, but residents of Houston don’t have a similar attitude about petrochemical engineers.

The right panel of Figure 2 is an idealized picture of how undersupplied housing affects internal migration patterns and creates a systematic downward competition for housing. Many readers are probably familiar with Evan Mast’s chain of sale research when a new home is built. We can also imagine a chain of displacement where new homes are not built.

Imagine an increase in demand for housing - it could be a child reaching adulthood, a family wishing to move into the city from elsewhere, or any number of the common reasons people demand more housing. Let’s say it’s someone at position 1 in Figure 2 - with a high income. If a new unit isn’t constructed for them, they inevitably must make a compromise between value and cost. They must choose a home that is less valuable than a home someone in position #1 would normally choose, and the only way to claim one in the absence of new homes, is to pay more for a home in position #2 until one of the families in position #2 is displaced. In order to stay in the city, the displaced family #2 has only one option: pay a little more than the norm for a home in #3 position until the marginal family in position #3 is pushed downward.

Anyway, this goes on, all the way down the ladder, until someone in position #7 has nothing to trade down to and they move to a city that looks like the left panel.

Now, that is the most extended version of a chain, but of course, there are many smaller chains. Maybe a child comes of age and starts a new household in position 3 and the chain starts there. Maybe someone moves to town in position 1 and the marginal family in position 2 that they displace decides to move away from the city, so the displacement chain stops there. Or, maybe a position 4 family wants to move to the city, realizes it is unrealistic, and never makes the move, so that the displacement is purely a lost opportunity of what could have been.

All of these little snippets of systematically downward compromises add up to that picture in Figure 1, where there is a linear connection from top to bottom in every city. The more the city is deprived of housing, the more that the cost of housing is a product of the income of other people, and the stress of that cost scales with your relative income.

On average, then, a family at position #1 will mostly trade off size, location, and quality for cost (elastic demand). Families at position #7 are less able to compromise away those things, and so they mostly accept higher costs, until those costs hit a tipping point and they must exit the city. In other words, in a city deprived of housing, the result is that at the top, families consume less housing, at the bottom families pay more for housing, and each aspect of those compromised housing decisions scales with income for all the households in between. This is the story of LA in Figure 1.

The pattern is triggered by the compromises that must lead to displacement, but the steepness of the line comes from families that resist displacement. The reason price/income levels are so high for the families with the lowest incomes is because the few families that remain are the families that self-selected to pay more rather than move.

So, how do you fix this pattern?

"We need 'affordable' housing, not market rate housing"

Let’s say that somehow, you could build all the housing the city needs, without any displacement, and insist that all of it is for families with below-median incomes. If you truly were able to achieve this feat, and the total number of units was enough to meet demand, you wouldn’t actually be stopping much of the displacement. In the description of displacement chains above, for every family in position #7 that must migrate away under conditions that we recognize as displacement under duress, there were countless other families who chose displacement at somewhat lesser scales of distress. So, even if LA could somehow impose this condition on new housing and still add units at the rate that Phoenix or Austin does, all the family decisions above the threshold will still be compromised decisions. All the stresses of an upward filtering housing stock will still be there. Those families will still be trading down into the stock of homes under the threshold. At most, this policy, at its idealized best, would lessen the displacement pressures on families below the threshold by giving them an option to be displaced within the city instead of being displaced out of the city.

So, imagine that a lot of new locations were created in LA for homes and a massive building boom was forced into those locations, only for “affordable” homes. Imagine Figure 1 looking like this.

Realistically, putting those sorts of limitations on new building would never remotely meet the demand for new housing, so in reality, you would create some more options for housing that would stem some of the worst outmigration (only if you actually increased the amount of building), but you would still be enforcing a supply constraint that would keep moving the line steeper, worsening the forces of displacement in general across the city.

Displacement with varying degrees of duress was happening from position 1 to position 7. At most, you’ve provided easier forms of displacement from position 4 through 7. Realistically, that harsh of a limit on the conditions of new units will likely also continue to steepen the price/income line.

Blocking Gentrification

Trying to save neighborhoods from new development also would lead to a similar outcome. In this case, think of the orange dots as existing housing whose costs have somehow been frozen in place by driving the demand elsewhere. Again, if there isn’t new construction for families with higher incomes, then this is like sticking the proverbial thumb in the dike. Freezing those units in place only diverts the displacement to other neighborhoods. The slope of the line will steepen just as it would have otherwise, but the distress and displacement will now be even greater in the other neighborhoods.

Rent Control or Subsidized Units

Rent control or subsidies have a similar dynamic. Here, imagine that you move some orange dots down or create new orange dots that are below the normal cost. This does still provide an outlet for a less extreme displacement for some families. But it still does nothing for all the displacement in the higher tiers, and if it isn’t somehow designed to increase the total housing stock, every dot that is pushed downward will put an equal and opposite pressure on all the other dots, pushing them upward. Like constricting the nozzle of a hose, the pressure of displacement will be greater on the remaining neighborhoods if you haven’t built enough new homes for all types of families to ease the pressure.

New Market Rate Housing

New market rate housing reduces the displacement all throughout the city. Since it allows for the most potential new building, it can actually flatten the slope of the line and fundamentally reduce the cost of low tier housing in a way that the thumbs in the dike of targeted housing cannot.

In fact, most of the new units will be built for families with higher incomes. The new unit for a family in position #1 is better than the new unit in position #7, because the new unit at position #1 stops an entire chain of displacement.

And, eventually, if you build enough, you get back to the the condition in the left panel of Figure 2 where some of the internal migration is upward instead of downward - where families move into new homes aspirationally, rather than as a budget compromise. In other words, not only are the low end homes cheaper, but now families from position #5 start claiming homes that used to have a family in position #4. That is how normal cities work!

Demanding only affordable housing means that when a family is displaced from a position #5 house, maybe there will be position #6 homes available to them so they don’t have to leave the city entirely. Building position #1, 2, or 3 homes means that families from position #5 homes start shopping for position #4 homes.

But most of the new market rate units are bought up by the rich families that don’t need it!

Yes!

So, how is the new market rate housing going to help the families who most need it if it just fills up with rich residents?

Well, first, as described above, it breaks the chain of displacement.

Thinking more generally, remember in the chain of displacement, the rich families were the families that reduced their housing consumption in order to keep their costs stable. Poor families were stuck in their existing homes with rising costs. That is the process that characterizes housing deprivation. That is the only way to get the right panel of Figure 2. Position #1 families trade down to lower their costs. Position #7 families that try to stay without being displaced must keep paying higher rents. That is the process that must be reversed.

What does reversal look like? It looks like rich families increasing their housing consumption and poor families living in the same units with rents that now decline.

Rich families claiming the new units is exactly what reversal of the problem looks like. It’s the only outcome that is a reversal of the problem. None of the other proposed solutions that involve targeted or subsidized units are reversals of that problem.

There is absolutely no way to fundamentally reverse the housing affordability problem with any of the other methods, because at the core of the chain of displacement, the motivation at each link is a rich family trading down into lower tiers of the existing stock of homes. The displacement comes from their contraction. If a city is very expensive, that is a result of its richest residents choosing to consume less rather than spend more, and that means outbidding a family that had previously claimed the house that, for them, is less!

If you aren’t building homes that “are just getting bought up by the rich”, then you can’t possibly be fixing your housing problem. At best you are making it worse in a way that is self-deceiving.

Am I saying that no displacement should be stopped, no housing should be subsidized, and no low-end housing or public housing should be built? Absolutely those solutions should be a part of every city’s housing process! The city in the left panel of Figure 2 will need all those things! But those are ways to help families, not to fix a city. And until the city is fixed, every attempt at a solution, including subsidies, will have negative side effects, even if the bad consequences are hidden out in the neighborhoods where you’re not paying attention. The only way to get positive results for all of those solutions is to first build a bunch of housing that will mostly be claimed by the families that least need it.

Someone who says “I’m against new market rate housing because most of the new market rate units are bought up by the rich families that don’t need it!”, isn’t just wrong. Make no bones about it. They are very specifically and fundamentally opposed to the project of creating affordable housing across your city. They are opposed to the only medicine that fully and functionally cures the housing supply disease.

Kevin, thanks for this beautiful explanation.

Exacerbating all of this is the fact that homeowners *like it* when the cost of the existing stock increases rather than decreases over time. Why shouldn't the original owner of a second-tier unit be glad that a rich person will buy their old unit at a premium?