When we lost our minds: Pt.1 Overview

This is the first of a 5 part (so far) series. It will culminate in a review of a 2015 article by UCLA economist Ed Leamer (of “Housing IS the Business Cycle” fame) on the lessons he’d learned in hindsight about the financial crisis.

The Big Short

I recently looked again at the ending of “The Big Short” to confirm that it reflected the public’s fatalism about the inevitability of the 2008 financial crisis.

In “Building from the Ground Up” I discussed “The Big Short” (the film). It is, in my opinion, by far the best film on the 2000s mortgage securities bubble. Between the first 3 minutes of the film and the postscript, it is a fun, masterful, dramatic telling of the details of the CDO market.

But, oof, those first 3 minutes and the postscript. It’s a great example of how having all the facts straight does you no good if your mental model of what those facts mean is inaccurate. And, it’s a great example of how the canonical presumptions about 2008 that are wrong create a lens that bends true facts into a predetermined myth.

The first three minutes is teeming with activity and production.

From my book:

The Big Short opens by zipping through the preceding twenty-five years in three minutes. It begins with the development of mortgage-backed securities in the early 1980s. Time-lapse footage of rising skyscrapers and scenes of bankers throwing cash at strippers crescendos with, “And America barely noticed as its number one industry became boring old banking. And then one day…almost thirty years later…in 2008…it all came crashing down.”

Out of two hours and ten minutes, I am only asking you to question three minutes of material. The three minutes that avoid detail. That foundation is what all of the precise details of the rest of the movie got built on top of—the idea that 2008 was just the final, inevitable act in a twenty-five-year-long drama. The canon determines which details we track and which details we ignore. The time-lapse footage of skyscrapers is a fitting metaphor for the divergent way that canonized knowledge directs our attention. The Big Short didn’t need to spend two hours convincing the audience that its setup was true, because the audience supposed that they already knew it was.

In truth, those time-lapsed skyscrapers were facing more and more legal obstructions. After 1980, Americans were investing less of their growing incomes each year into larger, nicer homes, not more. In some places, those homes were getting more expensive because it had become largely illegal to develop new housing nearby. The idea that bankers in the early 1980s created a monster that led to a thirty-year housing binge is simply backward. The late 1980s and 1990s saw, by just about any measure, the lowest rate of new housing production since the Great Depression.

The opening image of the movie is ironically set behind a quote from Mark Twain. “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The postscript is a series of screen texts. Here’s the first:

When the dust settled from the collapse, 5 trillion dollars in pension money, real estate value, 401k, savings, and bonds had disappeared. 8 million people lost their jobs, 6 million lost their homes. And that was just in the USA.

The opening was followed by two hours of surprisingly accurate detail about the CDO boom, but the idea that the postscript naturally follows from the events portrayed in the film really hinges on the sloppy presumptions of the first 3 minutes.

Long-time readers know that my position is that the entire $5 trillion loss of real estate value is due to the tightening of prime mortgage credit that happened entirely after the events of the movie were over. The reason I say that is because, on net, $5 trillion in losses after 2007 occurred in credit-dependent neighborhoods where housing markets had been benign during the subprime lending boom. (In “Building from the Ground Up” I also explain why the CDO boom, which was the focus of the movie, was different from the subprime lending boom. The conflation of the two is another part of how false premises led to poor judgment. The products the characters in “The Big Short” were trading were specifically designed to create new AAA-rated securities without requiring new mortgage borrowers, and the market for them arose after homeownership rates and home sales had started to decline.)

The audience is meant to attribute the entire $5 trillion loss, 8 million jobs, etc. to the events of the movie. Was there any reason for the audience to assume that? No. Not actually. The audience went to the movie with that presumption already pre-loaded. Total losses could have been $20 kabillion fabillion zillion, and that presumption would have held. Whatever scale of disaster might happen in 2008, it was pre-registered to have been caused by the banking activity in 2006.

How exactly would some bad financial securities cause 8 million lost jobs? I mean, one can construct a set of complex explanations. But why not 1 million or 20 million? If it just so happened that 8 million workers would lose their jobs after the CDO market collapsed, why would it necessarily be due to the thing we happened to just watch? A lot of things happened in 2006 that didn’t cause 8 million lost jobs. Maybe a CDO boom happened and also didn’t cause 8 million lost jobs.

The sloppy first 3 minutes of the film confirmed the audience’s mistaken impression that all this rigmarole was associated with decades of rampant production. The lost jobs, wealth, etc. were related to the deep drop in production that followed the events of the movie. And, surely that was overdue.

Since the crisis was assumed to be the reversal of all that phantom excess, the size of the crisis was assumed to be the measure of the excess. Post hoc ergo propter hoc.

Maybe if a nuclear bomb had hit New York City in early 2008, we wouldn’t have blamed the damage on the securities boom. I’m not sure much else could have broken the trance.

And, if there was a movie about a nuclear bomb that hit New York City, then a postscript that said “15 million lives were lost” would make sense. There would be a connection there. And if it said, “100 million” or “10,000”, we would react, “Wait a minute. That number doesn’t seem right.”

There is no basis for having that reaction to the claims about the damage blamed on the CDO boom. Pick a number, any number.

Post hoc ergo propter hocus propter hocus pocus.

Even though the sound of it is something quite atrocious.

If you say it loud enough, you'll always sound precocious.

Post hoc ergo propter hocus propter hocus pocus.

The first text screen is followed by these:

Michael Burry contacted the government several times to see if anyone wanted to interview him to find out how he knew the system would collapse years before anyone else.

No one ever returned his calls. But he was audited four times and questioned by the FBI.

The small investing he still does is all focused on one commodity: water.

and

In 2015, several large banks began selling billions in something called a “bespoke tranche opportunity.” Which, according to Bloomberg News, is just another name for a CDO.

The first screen is a bit of dramatic flourish, I think. As far as I can tell, Burry does have investments in water, but also mostly invests in various value stocks. The last screen is just the sort of silly conspiratorial thing that people who don’t have a lot of detailed knowledge of capital markets might worry about. Banks buy and sell financial risk in a variety of packages. Yes. Scary, if you think the last round of this caused $5 trillion in losses. Or if the entire concept of a “CDO” seems like a glowing rod of plutonium because the only reason you learned what a “CDO” was was to consume 2000s-era moral panic porn.

Anyway, the point of those ending screens was that the country is run by a bunch of corrupt numbskulls with their heads in the sand. This was just the beginning. Even water is at risk. The very accurate presentation of the CDO boom was bundled with apocalyptic conspiracies that surely, as time passes, we can all increasingly agree are a bit silly. With enough water under the bridge, even attributing the $5 trillion in losses to the events of the movie will seem silly to more viewers, too, someday. We can hope.

Again, this was so deeply embedded from top to bottom in our culture that I doubt there was a single review that said at the time, “Great movie, but those postscripts seemed a little silly.”

Kurt Loder’s review for libertarian reason.com, calls the movie, “Adam McKay's rocking adaptation of Michael Lewis' nonfiction bestseller about the 2008 economic meltdown, in which Wall Street shysters vaporized some $5-trillion in savings and real-estate value, and left millions of Americans jobless and without homes.” Post hoc ergo propter hoc.

The Global Glut of Capital

One way that the insanity played out was that top economists got in the habit of treating capital as dangerous. Here, I feel a bit like Scott Sumner frequently does. Like, how did the academy forget everything important on the topic of economics?

If you type “Bernanke gl” into google, it autocompletes to “Bernanke global savings glut”.

Since capital, and especially foreign capital, frequently takes the form of debt, Bernanke and others turned “Foreigners were investing billions into an American economy full of potential” into “America was going into debt”. Those are equivalent statements to an accountant. And, to make it worse, we seemed to be going into debt to buy imports.

The causality there is tricky and widely misunderstood. American corporations have highly lucrative international investments. Foreigners have to keep piling capital into American financial markets just to keep their own foreign profits from falling further behind Americans’. We reinvest some of our ample foreign profits abroad and buy imports with the rest. So, even though capital is constantly flowing into the US, we are not losing buying power. This has been the case now for decades. In effect, on net, American companies borrow capital from foreigners at, say, 5% interest, and invest it in foreign countries at 10% profits. There is nothing unsustainable about the trade deficit we have been running for several decades. We have a foreign profit surplus. Tom-a-to, tom-ah-to.

If there is anyone who needs to worry about sustainability, its the foreigners who have to keep producing and selling stuff to Americans because they need to in order for their profits on investments in America to keep up with American profits on our investments in foreign countries. Foreigners selling us our imports are the ones running on a financial treadmill.

Since 1970, the real value of US imports net of exports has added up to more than $66 trillion. No, we aren’t going to have to come up with $66 trillion to pay that back. We already paid for it with the profits of our past investments, because Americans are good at this.

The global savings glut and the related trade deficit seemed to be associated with a decline in manufacturing (because we were buying goods from foreigners) and a boom in home buying and housing construction (funded by borrowing all that foreign capital).

In 2005, Bernanke said:

In particular, during the past few years, the key asset-price effects of the global saving glut appear to have occurred in the market for residential investment, as low mortgage rates have supported record levels of home construction and strong gains in housing prices.

Also:

(M)uch of the recent capital inflow into the developed world has shown up in higher rates of home construction and in higher home prices. Higher home prices in turn have encouraged households to increase their consumption. Of course, increased rates of homeownership and household consumption are both good things. However, in the long run, productivity gains are more likely to be driven by nonresidential investment, such as business purchases of new machines. The greater the extent to which capital inflows act to augment residential construction and especially current consumption spending, the greater the future economic burden of repaying the foreign debt is likely to be.

And:

In the United States, for example, the growth in export-oriented sectors such as manufacturing has been restrained by the U.S. trade imbalance (although the recent decline in the dollar has alleviated that pressure somewhat), while sectors producing nontraded goods and services, such as home construction, have grown rapidly. To repay foreign creditors, as it must someday, the United States will need large and healthy export industries.

Oof. No. We don’t need to pay off our foreign creditors. If they don’t want to make loans to us any more, they can swap the debt for some shares of Google.

One of my Mercatus papers is a fundamental response to some of this. Home values in the United States have been inflated by rents, not by low interest rates. I write a lot about this at the substack too.

Bernanke here is basically saying, “Look, low interest rates are creating more homes and more construction jobs, but it’s not my fault.” When the crisis hit, a popular retort to this was, “See, it was Bernanke’s fault. He created those jobs!” Everything about this debate is nonsense.

Jobs are good! Houses are good! Capital is good! Honest!

Those “record levels of home construction” that Bernanke (as was the convention) was imagining, didn’t exist.1 At best, American construction activity was struggling to maintain long-standing trends. (Figure 1 shows real per capita consumption of housing, estimated by the BEA.)

The reason it was struggling, and the reason construction activity seemed disruptive is that an important portion of American metropolitan areas had clamped down on housing so hard that even just sustainable growth in the housing stock forced a national migration event, as families had to move out of the stifled cities and into cities that could still build.

And, that process was moderated through financial distress. Rents had to rise high enough to make someone give up and move. And prices rose with them. High rents were the fundamental source of the demand for capital from homebuyers, not low interest rates.

Bernanke was wrong about residential investment’s effect on both productivity and trade. There are few broad categories of investment more valuable than residential investment. Home construction will increase worker incomes, mostly, by lowering the cash transfer from workers to land owners.

It is true that debt interacts a lot with real estate, and can provide liquidity to spend real estate windfalls. It also is true that those real estate holdings were unproductive. But, they weren’t unproductive because they were homes. They were unproductive because we weren’t building enough homes and the owners of the existing homes were getting a windfall. The land value under the homes was inflated. Since they were earning excess rents, and their properties were valued based on future excess rents, they were able to consume more, even though they weren’t producing anything.

Again, though, it was the high current and future rents that were the base cause of the windfall. Not foreign capital and low interest rates. And the way to reduce it was to take in the foreign capital and build more homes with it. Bernanke’s dismissal of new home construction as unproductive was sadly off-base.

This all comes from presuming that foreign capital or low interest rates were the fundamental cause of high home prices, and that presumption makes it easy to further presume that we were overproducing homes. And the proof seemed to be that prices were rising more than rents were. But, rising price/rent ratios are mostly caused by rising rents. This is admittedly counterintuitive.

However you look at it - over time, across metro areas, within metro areas, price/rent ratios are always higher when rents are higher. And, I hope that with 20 years of hindsight, after housing production was crippled, and now unprecedented rising rents have been associated with new highs in price/rents, this is more obvious. And, now, even mortgage rates have risen back to previous levels, to help remove any remaining doubt.

Bernanke’s view is common among schools of thought like Austrian business cycle proponents and their cousins. Capital was misallocated, they say. Or, remember Ed Leamer, in August 2007, speaking to Federal Reserve members when housing starts were already down 40% and dropping like a stone, chiding them that, unfortunately, recovery was not likely because the Fed had already set us on the way to recession in 2005 by supposedly pushing interest rates too low:

The inevitable effect of those rates has been an acceleration of the home building clock, transferring building backward in time from 2006-2008 to 2003-2005. Our Fed thus implicitly made the decision: more in 2003-2005 at the cost of less in 2006-2008. That strikes me as a very risky choice. The historical record strongly suggests that in 2003 and 2004 we poured the foundation for a recession in 2007 or 2008 led by a collapse in housing we are currently experiencing.

I know, macroeconomics is hard and frequently counterintuitive, and it might be reasonable in some technical way at some times to say that there are too many jobs because of inflationary stimulus. It starts getting very slippery when you start singling out individual sectors and targeting a cap on their individual growth paths.

As for economists like Leamer and Bernanke, both real production and inflation were pretty normal before 2008 - near the median of post-World War II data. Running a little hot, but less so than most post-World War II expansion periods. Their acquiescence to the economic collapse wasn’t justified by broader economic data.

At the end of the day, everyone here was befuddled by model error. They didn’t understand that high rents were creating the distortion from historical trends in housing, and so they all were engaged in the Socialist Calculation Problem. Since they didn’t understand why home prices were so high, they figured the prices must be too high, and we must have too many of them. And, so a dozen different proponents of different false causes of high home prices all agreed on the most important myth - housing needed to be throttled. And since they all agreed, it seemed unlikely to all of them that their “Socialist Calculations” could be wrong.

The recession was so deep because everyone agreed to keep turning the dials down on everything else until housing broke. And, even then, it took manually breaking the mortgage market to get the job done.

The debate has been explicit on this. Economists thought the problem was capital. And the problem with capital was that it created jobs and homes. Now, after acting on those presumptions we have less of both of them, and it has had very regressive consequences.

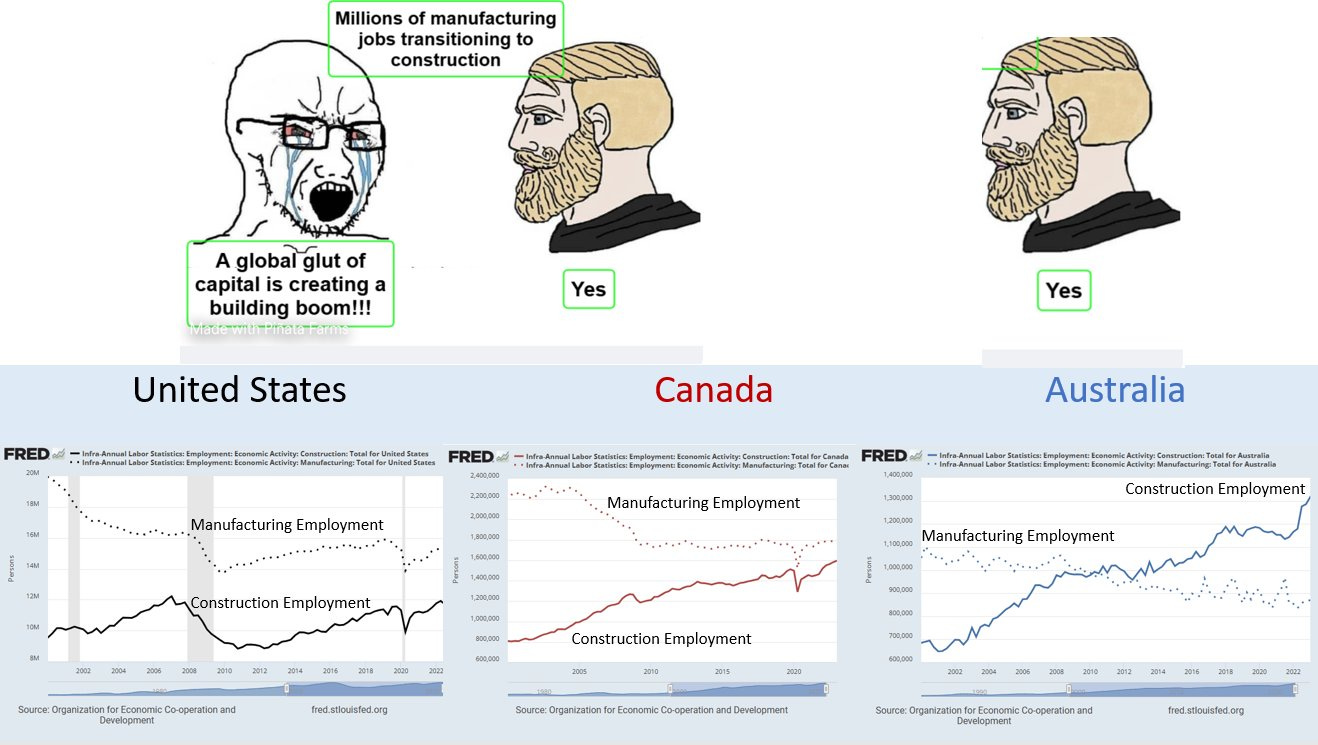

On this topic, I put together a meme. Figure 2 compares trends in manufacturing employment and construction employment in the US, Canada, and Australia.

One of the oddities of their line of thinking is that the counterfactuals are just sitting in plain sight. In all three countries, manufacturing employment has declined by about 20% since the year 2000. In the US, construction employment hasn’t made up for that. In Canada and Australia, it has more than made up for it. (Technical note: The measure in Figure 2 is for total construction employment. Not just residential construction.)

Projecting, calling for, and then approving of the construction employment trend that the US has had since 2007, oddly, has been the road to status among American economists. “Our guest today is famed economist, Dr. X, who is known for complaining about construction jobs as early as 2002.”

Figure 3 compares the combined totals of manufacturing and construction employment since 1990 in the US, Canada, and Australia.

Canada and Australia simply accepted the capital and built homes with it. Manufacturing jobs have declined, and they have been replaced by construction jobs. Those concerns of Bernanke and Leamer were fever dreams. We engineered that very odd employment collapse in the US in Figure 3. This outcome was very clearly the policy goal.

How bad was our error? Well, with all the additional construction, are Australia and Canada swimming in cheap rents and vacancies? They are just a bit closer to reasonable than we are. Even they could have used more construction.

The policies associated with it were announced, then implemented, and then in hindsight confirmed with self-approval. The only complaint Leamer had in his 2015 paper, which is the conventional reaction, is that the disemployment should have happened earlier.

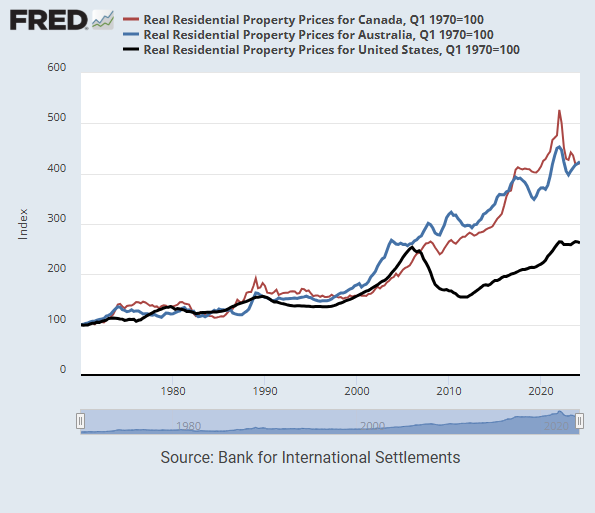

Figure 4 compares the home prices in the US that added up to $5 trillion in losses to prices in Australia and Canada - the $5 trillion that didn’t require any explanation for “The Big Short’s” viewers and Ed Leamer’s readers because its inevitability was so obvious to them.

Ironically, but inevitably if you think about it, since the real cause of the financial crisis (overtightened lending after 2007) doesn’t even appear in the Table of Contents of Great Recession retrospectives, the actual cause of $5 trillion in lost wealth, lost jobs, etc. is highly over-identified.

High rents caused high home prices and the mortgage clampdown caused prices to crash. Since nobody controls their model with these variables, all of the outcomes those factors created are free for other variables to claim. So, the various causes of increased economic activity before 2008 have collectively explained 500% of the boom and bust.

Oddly enough, the outcomes in Figure 3 & Figure 4 are confirmation for everyone that they were correct. The loss of $5 trillion confirms to the “The Big Short” audience that those bankers were reckless.

In his 2015 review article, Leamer also blames the bankers in “The Big Short” for causing the price collapse. Leamer had argued in 2007 that prices shouldn’t decline significantly. Mostly housing construction declines into a recession, more than prices. So, in hindsight, he concludes that the bankers caused the price collapse that caused his model to be off this time.

(Of course, his model is actually great! It was the mortgage crackdown that came after his 2007 address that made this time different. And Leamer should have used his model to argue for an earlier recovery in housing starts rather than supporting the decline he expected to be recessionary. But, his “socialist calculation” said we had too many homes.)

Figure 5 is housing starts in Australia, Canada, and the US, relative to the 1965-1995 average. I have highlighted 3 points in time to help you follow Ed Leamer’s evolution in thinking.

There will be a recession because we have 1 million too many new homes.

There will be 1 million permanently unemployed workers because at the low rate we’re building homes, we don’t need them. What we have learned, now, is that we should have reduced housing construction earlier.

We’ve had a housing shortage for at least a decade. (More on that in part 4.)

I suppose the good news is that, at least, for the first time, he’s not calling for permanent unemployment in a desperately undersupplied sector. Take your wins where you can get them.

The Midwest

Finally, one response to this might be, “But, the construction jobs and the manufacturing jobs are in different places. One wouldn’t really have replaced the other.” I used to ascribe some value to that reply. I don’t so much any more.

First, it’s based on the wrong notion that our housing cost problem is due to “superstar” cities, and they just can’t build fast enough to keep up with demand of workers wanting to move there. It is quite the opposite. Residents are moving away from the “superstar” cities because they are actually “loser” cities that block housing.

There is this idea that we have economically successful, expensive growing cities on one end of the spectrum, and cities with declining manufacturing at the other end of the spectrum. That’s the way economies usually work! People move to where the jobs and high incomes are.

There aren’t a lot of jobs in New York, LA and San Francisco. There are potential jobs that people imagine would be there if workers could move there. How would we know? If there are jobs there, nobody can move there to claim them.

Because of the shortage of housing the US does not have the traditional migration pattern.

Notice in Figure 6, Midwest population growth outpaced the Northeast by about 3% from 1990 until the financial crisis. Since then, growth has been about the same in both regions.

Now the Midwest is house-poor like the Northeast is. The region that was hit the worst by the construction bust was the Midwest. New home sales there fell to new lows and stayed there.

As I mentioned in a recent post. The Midwest used to have moderate rents while the “superstar” “loser” cities had excessive rents. But, since thousands of construction workers became permanently unemployed, rent inflation in the Midwest has been nearly as excessive as it is in other regions.

The American economics academy decided capital, jobs, and houses were bad, and workers in the Midwest got permanent unemployment and rent inflation. And the leading academics and policymakers have connected all the dots for us. This was not an accident.

Without the housing bust, workers in the Midwest might have been able to move to places with better economic prospects, but also, there was plenty of potential for them to have better economic prospects at home - including through local construction employment since 2008.

And some of that construction would have been to build homes in the Midwest for some of the millions of Americans that have to move away from the underhoused coastal metropolises. That’s not ideal. But, the solution to that problem isn’t to stop building houses in the Midwest!

Economic leaders like Leamer and Bernanke weren’t necessarily to blame for the extreme tightening of credit standards on new mortgages, which was the real culprit for the crisis, the unemployment, and the subsequent housing shortage. But when the damage of that change struck us, work like theirs had set in place baseline expectations that made those ridiculously large disruptions seem inevitable and proper.

When “The Big Short” was telling viewers that “8 million people lost their jobs” in 2015, Ed Leamer was still sure that 8 million hadn’t been enough.

To this day the debate remains unresolved and ongoing about whether Bernanke’s Fed or foreign savers were to blame for attracting capital into the American economy and creating jobs and homes. Talk about presumptions determining how productively you can analyze facts!

When We Lost Our Minds:

Part 1: Overview

Part 2: Respecting the Timeline

Part 3: The Dog that Didn’t Bark - Retirement Homes

Part 5: The Lessons Leamer Learned

He was probably referring to sales of single-family homes, which were at record highs. Since that was really the only category of housing about which you could say that, it was the commonly cited measure at the time. This was the result of the housing shortage, because Americans everywhere had to sort out of undersupplied apartments into the single-family homes that cities favor, and they were also moving from inflated apartments in undersupplied New York and LA into more affordable single-family homes in other cities.

Using a measure such as residential investment as a percentage of GDP, home construction was momentarily near the high end of the long term range after a long downturn, but was not unprecedented.

This is a copy of a chart Bernanke used on this topic, which I discussed in my book “Shut Out”. The nomenclature “Global Financial Crisis” (which is mostly about the breadth of the financial losses from the US real estate bust) and the common confidence in this supposed relationship is odd. The only other countries that really shared a real estate bust with us were Spain and Ireland.

But, you know, I’m not sure I’ve ever quite thought of another oddity with this chart. Spain and Ireland are way above the regression line here. Their home prices were high, even considering the capital inflows. But according to Bernanke’s chart, home prices in the United States were actually at a level associated with a trade surplus! Think of what an outlier we were by the end of the crisis. Surely we were below the x-axis by 2012!

If Bernanke’s theory was correct, he should have been perplexed in 2007 about why home prices were so low!

I like a lot of this. Of course the financial crisis was not cause by bad mortgages. It was 100% created by the Fed that refused to keep inflation up to target. Yes many financial sector firms would have, should have lost all their equity, but not more than a few house owners, no unemployment, etc.

Excellent post, but I will have to read a couple more times.

I also wonder about the global "capital glut."

One response: There are no bubbles, no shortages and no gluts. Only supply and demand.

But...in fact, many nations globally suppress consumption, and funnel non-market savings money into investments, China being the prime example but also Germany, Singapore, any number of Asian nations. I have to say, this strategy seems to work.

Having "too much" capital might not be a bad thing, but I suspect then returns on investments are artificially suppressed.

I have reservations whether the US employee classes have benefitted from the last 50 years of globalism.

Foreign capital buying the best real estate to live in...that is what happens in Third World nations...and now the US and Greece too. Of course, this problem is exacerbated by the outlawing of new housing construction in much of the US.

Michael Pettis has an interesting take on international trade, and I think a worthy one.