I had planned on a 4 part series, but Leamer’s 2007 presentation to the Federal Reserve really deserves a thorough review in its own right, so I am going to devote this entire post to that. In part 5, I will review what he had to say in hindsight, in 2015.

Leamer’s Very Useful Model

The patterns Ed Leamer uncovered in his 2007 paper, “Housing IS the Business Cycle” are very useful. It seems true and important that declining housing starts is an important early signal of a coming recession.

He has a reasonable conceptual framework for arguing that monetary policy will be more effective if it aims to slow housing production earlier in the cycle. The risk of waiting too long is that then the Fed is left scrambling to pull a too-hot market back, and risks being procyclical.

That’s all well and good if you know how many houses we need.

Because he accepted the mythologies of the day, he, infuriatingly, decided that the Fed was already too late this time. They had let the boom get too hot. Instead of avoiding the bust in 2008, he concluded that it should have avoided the boom in 2005.

By the way, Leamer writes with a sort of smugness, or swagger, that I sense is somewhat like my own writing style. And it doesn’t come off well at all if you think he is wrong about a lot of things. I feel like if I had the appropriate amount of humility, this would cause me to recoil from this review, in fear of looking the fool, myself. But, I guess I lack that amount of humility, which is concerning.

The Fed was late to loosen.

Figure 1, from one of my Mercatus papers, compares the rate of new housing production at the peak of the last 6 expansions. Peak building is matched at t=0. The chart shows how active building was, per capita, in 2006 compared to previous expansions and it also shows the point in 2007 when Leamer counseled the Fed that recession was imminent because our building boom had been so vast. In the past contractions, he would have counseled to immediately stimulate until starts recovered, but not this time.

As I reported in Part 1, he said:

The inevitable effect of those rates (KE: rates that he thought were too low before 2006) has been an acceleration of the home building clock, transferring building backward in time from 2006-2008 to 2003-2005. Our Fed thus implicitly made the decision: more in 2003-2005 at the cost of less in 2006-2008. That strikes me as a very risky choice. The historical record strongly suggests that in 2003 and 2004 we poured the foundation for a recession in 2007 or 2008 led by a collapse in housing we are currently experiencing.

Let me be clear. Leamer, at the spot marked on the chart, was arguing that the Fed needed to hold off on stimulus, because they had let the housing market get too hot, and there was no room for a new expansion.

The mark about Bernanke is where he reported to Congress that the broader recovery was still slow because we were still working off the excess housing supply.

Leamer has a section about how real US GDP growth has been reliably 3% annually for decades, through all sorts of debacles. “Fiscal and monetary policies have had negligible effects on long-run growth.” What’s important is smoothing out the ups and downs.

This is a solid point. It’s why I ascribe to the market monetarist school of thought of targeting a nominal GDP growth rate. With stable monetary policy, real growth shouldn’t have permanent losses.

Oof.

The steep, permanent drop in real GDP happened mostly in the 2nd half of 2008 and the first half of 2009. I wonder what would have happened if the Fed had targeted a recovery in housing starts by mid-2007.

Housing IS the business cycle

At Jackson Hole, in August 2007, in this presentation, Leamer displayed a series of definitive charts, making clear that regularly in post-WW II cycles, “residential investment is subtracting from GDP growth before the recession but starts to contribute more than normal in the second or third quarter of the recession.”

He shows a chart of how steeply residential investment was dropping before each recession, and how quickly it was contributing to recovery once each recession had started. He also included the 5 quarters ending in the first quarter of 2007. Those 5 quarters were the deepest, steepest drop of any of the 10 previous recessions! And that was already 2 quarters old, and it had only gotten worse by the time he made his presentation!

Residential investment started contributing negatively to real GDP growth in the 4th quarter of 2005 (nearly two years before his presentation), and didn’t contribute positive growth until the 2nd quarter of 2009.

In the next section, Leamer discussed prices, which he noted tend to decline, gently if at all, well after construction trends decline. (I wonder if prices would have been firm if the Fed had targeted rising housing starts by mid-2007.)

Los Angeles. . . Los Angeles?!

Here, I think the considerations of the effects of local supply constraints would have been helpful. A consideration of filtering in the existing housing stock, in extremely tight supply conditions. The regressive rent and price trends that mathematically must arise from the curtailment of normal filtering when supply is extremely tight. And the migration and depopulation that come along with extreme supply deprivation.

Those were all relatively new issues. Leamer is at UCLA, so he lives in a Closed Access city, but by all appearances in this paper, he seems unaware of the implications of deep supply deprivation.

Leamer commits a subtle error here that I see time and time again in the conventional literature, both statistically and rhetorically. It’s a sort of unintended subtle question begging. The researchers would have no way of knowing they are begging the question. They don’t know about the question.

The housing market was very regional by the 2000s. The Closed Access markets were very expensive. Millions of families had to move away from those markets. And those people created hot housing markets in the cities they moved to.

So, there was a sharp distinction. All the markets looked “hot”. But, can you call a city that’s bleeding residents by the hundreds of thousands, where high housing prices are driven by perpetually rising rents, “hot”?

The hot markets were the places those residents were moving to.

The market Leamer chose, to consider the possibility of price volatility and to look at evidence of excessive lending, was Los Angeles. The capitol of the Closed Access cities. Why did he choose Los Angeles? There could be a lot of reasons.

But, if he had chosen any of the truly “hot” markets that were building a lot of homes that really were selling at unsustainably high prices (though not building at unsustainably high paces) - cities in Nevada, Arizona, and Florida - he wouldn’t have found the pattern he found.

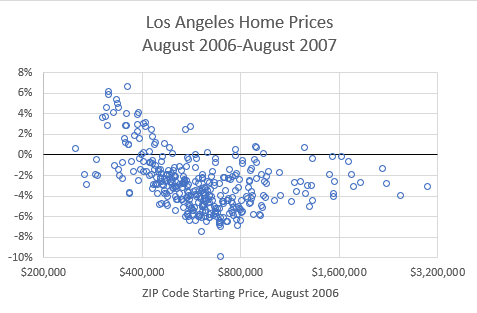

The title of this section of the paper is: “Evidence of Diminished Underwriting Standards: Appreciation Greatest for Cheaper Homes”. And, very reasonably, he takes the appreciation of lower-priced homes in Los Angeles to be evidence of loose or reckless lending. Very reasonably, but in this case, largely wrong.

Upward filtering under extreme supply constraints was causing most of those price differentials in Los Angeles.

A consideration of Parts 2 and 3 in this series of posts might have been helpful.

There likely was a bit of a bump in late cycle lending, as I described in Parts 2 and 3, but amounting to a very small portion of the total rise in prices, and certainly not associated with any increase in construction.

In the 12 months leading up to his presentation, the price trends in Los Angeles, shown in Figure 3, looked a lot like price trends in Phoenix that I noted in Part 3. The last of the lending in the subprime boom might have been helping low end home prices to remain stable while high end prices were already declining.

Ruminate on this chart for a second. What did Ed Leamer, himself, tell us in this presentation? Declining prices lag the building cycle and they are usually not large.

So, where does Figure 3 put us in the building cycle, in August 2007? New housing permits had been declining sharply since the end of 2005 and now prices in the richest neighborhoods were declining, in nominal dollars. (In Leamer’s defense, the price data was still too fresh at the time to notice. The permits and sales data, however, was not.)

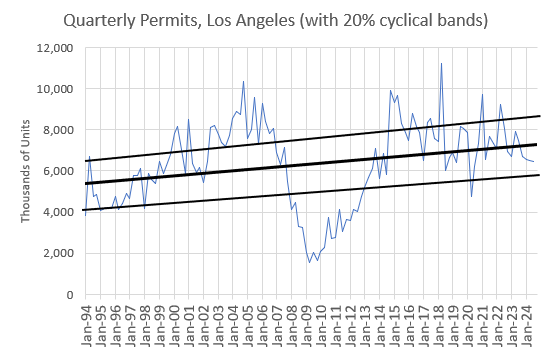

One back-of-the-envelope estimate of the housing cycle that Leamer recommends is a 20% band around long-term trends. He actually walked through the housing data for Los Angeles, where prices had nearly quadrupled in a decade, and reiterated from that, “It’s a volume cycle, not a price cycle. And it’s starting again. The December 2006 volume is off 29% from the peak in March 2004, and prices are levelling off, but not declining (so far).”

Figure 4 shows quarterly housing permits in the Los Angeles metro area over time, with the trendline and +/-20% bands. From 2002 to 2006, Los Angeles was “hot”. And, then it reversed sharply, and was crossing the negative 20% line as Leamer spoke.

Let’s compare Los Angeles housing production to the national numbers. The sustainable rate of permits before 2008 was somewhere north of 5 units per 1,000 residents. The US had peaked at about 7 in 2005.

When Los Angeles went over the +20% band, permits per 1,000 had risen from about 2 to more than 2.5 units. Tens of thousands of households were moving away every year because of rising rents.

Had the Fed accelerated “the home building clock, transferring building backward in time from 2006-2008 to 2003-2005” in Los Angeles, leaving no potential for housing construction to rebound in 2008? This appears to be his point.

As I have noted elsewhere, housing supply has become so fixed in cities like Los Angeles that cyclical changes in demand for housing must be accommodated with countercyclical population growth. You can see that in Figure 5.

Leamer must simply be unaware of the most pressing economic issue of our time. An issue that his own city is the prime example of. The business cycle in Los Angeles can mostly be measured by the number of housing refugees it creates in a given year.

Of all the cities in America, to pick Los Angeles as the regional example that housing “is a volume cycle, not a price cycle.” is frankly stunning. There is no volume cycle in Los Angeles. And, since there is no volume cycle in Los Angeles, it now has a price cycle.

No, we didn’t transfer housing back in time, for Pete’s sake.

It can be very useful to be sensitive to changing residential construction trends as a leading indicator of coming recessions. And it might also be useful to moderate the top of the cycle as much as it is to avoid the bottom. But, when you build a house in 2006, it absolutely doesn’t preclude building another one in 2008. That’s ridiculous.

People have a million different ways to use housing. Quantity demanded doesn’t live on a knife’s edge. Figure 6 shows the number of housing starts in any 5-year period as a percentage of the housing stock, since 1969.

My basic point here is that the variation from the bottom to the top of a building cycle usually amounts to a cumulative change in the housing stock of about 1%. Yet, over time (and, by the way, population growth was pretty stable from 1969 to 2008), the change in the secular marginal demand for new homes has been of a much larger scale.

Even if there is some argument that this could be the case in some context, it wasn’t the case in 2007, and it sure as heck isn’t today. Increasingly, rent doesn’t pay for the roof over your head. It pays for the permission from the city that comes with your plot of land, for a very particular, approved roof over your head.

In this context, every new home transfers some of those land rents back to being rent for the structure. We are nowhere near a context where we could have too many. Consider what you get for $3,000 in Los Angeles compared to what you get for $3,000 in Charlotte. What exactly is going to get in the way of Angelinos consuming houses like Charlotters do? (Charlottans? What do you call people from Charlotte?) When homes in Los Angeles get to be, say, double the rent of similar homes in Charlotte instead of triple the rent, will Angelinos suddenly hit a wall? Of course not.

I suppose you might be thinking that Charlotte hit a wall in 2008. No. Construction in Charlotte didn’t increase during the 2000s. The collapse that every city experienced had nothing to do with supply.

Benchmarking to deprivation

Leamer analyzes the yield curve, inflation, and housing starts in every cycle since 1961. He treats 2% inflation has the neutral benchmark and 1.5 million housing starts as the neutral benchmark. He uses that benchmark for 1961 America, with a population of 184 million and for 2007 America with a population of 302 million.

Why? Because the naive trendline was a flat 1.5 million units.

Every major city over the previous half century had put obstacles in front of urban housing production, and a handful of cities had put such obstacles in front of it that even before we get to a cyclically neutral rate of construction, they trigger massive local rent inflation and the forced migration of hundreds of thousands of households annually.

Since he was unaware of this, or at least not focused on it as a central factor in the processes he was studying, he simply was benchmarking monetary policy to decline and deprivation.

A couple times he mentions, “absent a change in the technology for transforming residential land into housing services, the contribution of our residential land to GDP is about the same now as it was five years ago, but on our hard drives we are recording real values for this land that are double what they were.”

I think what he’s trying to say is that the value of homes comes from the service of shelter. If the rents stay the same and the homes stay the same, but their prices double, that’s not really a reflection of communal wealth.

This is very true. But, he makes the mistake that is very common among economists of blaming the high prices on things like low interest rates.

I don’t know what he is referring to specifically in the comment above. Real rents as a portion of GDP or nominal rents as a portion of GDP?

Nominal spending on rents had been somewhat level as a portion of total production. But that has been a combination of perrenially underinvesting in residential structures while the rents on those structures (or more accurately on the land under the structures, or even more accurately as legal permission for a residential structure) become inflated. That steady level of spending was part of the long-term process of deprivation. And that is why the land value under the houses was elevated. Not Federal Reserve interest rate targets.

Figure 9 is from my Mercatus paper, “Rising Home Prices Are Mostly from Rising Rents”. In terms of Leamer’s model, what is clear here is that if construction isn’t severely obstructed then “housing is a volume cycle, not a price cycle.” If construction is severely obstructed then housing is a price cycle and not a volume cycle.

And you can tell if its turned into the latter by looking at rents. If the houses are staying the same but rents are going up, then you have transitioned away from the Leamer world to our world.

Ironically, in late 2007, Leamer saw a housing market that had become a price cycle. The only way out of a price cycle is to build until you can get back to a volume cycle. But, if you think the volume cycle is a state of nature rather than an economic garden that must be nurtured, a price cycle just looks like history’s biggest volume cycle. (Basically a version of the “world’s most niche meme” error.)

Los Angeles, the city Leamer cited as the former, has very high prices because it has very high rents. It has very high rents because it permits 2 units per thousand residents. If the whole country was like Los Angeles, we would never even get close to Leamer’s 1.5 million production target.

Oh, wait. We actually managed to do that. And the whole country now has a price cycle, not a volume cycle.

We should aspire to live in the world that Leamer’s paper would apply to.

When We Lost Our Minds:

Part 2: Respecting the Timeline

Part 3: The Dog that Didn’t Bark - Retirement Homes

Part 4: Leamer’s Counsel

Really appreciate this post. I think foiling Leamer's models with what we know now and drawing out the logic errors present in his analysis is one of the more effective methods for communicating the challenges in the housing market.

One thing I'm still curious about is the specific mechanisms that changed in the 2007 to 2009 time-period beyond interest rates. What exactly was done to so severely curtail lending? What conversations were had? What assumptions/arguments? Is this primarily a Fannie/Freddie issue? I'm trying to grapple with where do we go from here.

Third chew: I'm not sympathetic to predictions about recessions and boom that do not explicitly model central bank behavior. Now I agree that housing is more sensitive to Fed policy than most sectors so what is going one there deserves special attention in Fed decision making but ultimately it's only one input (as is the unemployment rate) into what the Fed should be doing to inflation.