In 2015, Ed Leamer wrote a retrospective about his 2007 presentation to the Federal Reserve. (The paper was published in 2015, but it looks like he wrote it in 2013 or 2014.) It was titled, “Housing Really Is the Business Cycle: What Survives the Lessons of 2008–09?”. He concluded that subsequent events confirmed that he was right, and that the Fed’s main mistake was not slowing the market down years earlier.

He lists these 4 points from his paper:

(i) Housing is the single most critical part of the U.S. business cycle, certainly in a predictive sense and, I believe, also in a causal sense.

(ii) The proper conduct of monetary policy needs to be cognizant that choices made at one point in time affect the options later. It is an intertemporal control problem.

(iii) The best time to intervene in the housing cycle is when the volume of building is above normal and growing more so.

(iv) Homes experience a volume cycle, not a price cycle.

The first three of these have been strongly confirmed by the 2008–09 downturn, but the fourth has not. This time housing has had an unusually strong price cycle as well as a volume cycle. The difference, I think, comes from the extreme and prolonged deterioration of lending standards in 2001-05 made possible by “innovations” in mortgage securitization and supported by the Fed’s easy money policy.

Right there, in a single paragraph, he concisely outlines the basic problem that has kept economists in the dark on this.

I agree that all of the first three points are correct and were confirmed, as concepts, by events. The question that remains, in practice, is what is the cyclically neutral rate of building? And, the problem for Leamer is that non-monetary factors had routinely driven American construction rates too low.

The Socialist Calculation Problem

The question that his first three points don’t answer is: Do you slow down the market when it’s above 500,000 units a year? 1.5 million a year (what he chose)? 3 million a year?

What would happen if the Fed regularly slowed the economy down when housing production was still low? Rent inflation would be perpetually high. Other inflation would be perpetually low. That had been the case since the mid-1990s. In 2005, housing completions briefly touched an annual rate of 2 million. And, as shown in Figure 1, briefly, in 2005, shelter inflation and core consumer inflation excluding shelter briefly met literally right at the Fed’s 2% target.

For most of the preceding decade, core CPI excluding shelter had been below the 2% target and shelter (rent) inflation had been above it. As soon as construction started to collapse, they parted ways again.

When Leamer was telling the Fed in August 2007 that low interest rates had overstimulated the economy and the housing market, core CPI excluding shelter was 1.1%, core CPI was 2.1%, and shelter CPI was 3.4%.

When the Fed had initially started raising its target interest rate in June 2004, which Leamer had argued was too late, core CPI had been 1.9%. That was a combination of Shelter inflation of 3% and core CPI excluding shelter of 1.1%.

Between those two points in time, core CPI excluding shelter was never higher than 2.1%.

It’s ironic that Leamer’s position is popular among right-leaning economists, because it is a natural proof of the Socialist Calculation Problem. They have all the concepts right. They have the math wrong. They keep benchmarking to housing production too low and a Fed target rate too high, producing excess rent inflation that only refuels the miscalculation. As “The Big Short” put it in part 1, “And then one day…in 2008…it all came crashing down.”

The Regional Supply Shortage and Its Victims

The building boom had brought rent inflation in the Closed Access cities (New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego, and Boston) down from around 6% in 2001 to a bit over 3% in 2005. But, since those cities don’t have a volume cycle, they have a price cycle, the homes had to be built in other cities, and a disruptive migration event ensued.

You could say that the endemic regional shortage of housing does make it important for the Fed not to overshoot during expansions. But that isn’t because the economy was above its broad, non-inflationary growth potential or because there was a surplus of homes. It’s because the Closed Access cities have such a shamefully low growth potential that they create a migration event whenever the growth is high enough for the rest of the country to be near its potential.

So, the housing market before 2006 had 3 broad regions:

Most of the country, where rents were moderating, construction was normal, and prices were moderate.

The Closed Access cities where rents must rise to the level necessary to push financially disadvantaged locals out. Prices there were very elevated and regressively so.

The Contagion cities, which are the cities in inland California, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida, that were taking on the bulk of those refugees. They traditionally had high rates of construction, but the migration surge overwhelmed them. Prices in those regions spiked, but not in the way that it had in Los Angeles. Prices increased broadly across those markets, in both rich and poor neighborhoods. And the spike was so acute that it outpaced rents in the short term.

If you average those regions together or throw them all in a data set that doesn’t distinguish between them, in 2005, you get national averages of moderate rent inflation, sharply elevated home prices (especially in poorer, credit-dependent neighborhoods), and increased housing construction. There was not a single location that had those characteristics.

Since Leamer had no reason to doubt his first 3 propositions, and he apparently didn’t have any idea about these supply dynamics, he naturally explained the failure of the fourth proposition with low interest rates and loose lending. They were true, actual things that had existed. And they reasonably could hypothetically explain why the proposition failed, even if they didn’t actually explain it.

Errors of Omission and Commission and Omission

And, so, his ignorance of the supply dynamic created errors of both omission and commission. It caused him to misestimate the cyclically neutral construction rate, and it caused him to overestimate the importance of low interest rates and loose lending. And, then, this led to a follow-on error of omission, because now, the extreme tightening in mortgage regulations that was the actual reason for both the deep drop in construction and the unusual drop in prices, is nowhere on his radar. It seems like mostly a correction from the overestimated credit boom that filled in the gaps that constrained supply would have explained.

Leamer wrote, “When evaluating the accuracy of recession alarms from the housing sector we need to look at false positives as well as false negatives.”

I agree. I think he should have applied that discipline to alarms about expansions too. He didn’t, so his false positive of overbuilding during the expansion led him to abandon his own model and to pronounce a fatalism about the coming recession.

Unfortunately, the very low fed funds rate in 2002–04 did not transfer building forward in time since there was nothing to transfer. Those rates transferred building that would otherwise have occurred in 2006, 2007, and 2008 back into 2003, 2004, and 2005. In other words, the housing downturn was built by the Fed…

(F)or durable volumes a bubble means building a stock of durables that exceeds the needs of the population, and a recession is a time-out to allow the population and economic growth to catch up to the existing stock and/or to reduce the stock by depreciation. The only way to stop a durables cycle is to intervene to prevent the stock from becoming excessive, which means high rates of interest when housing starts have been above the normal 1.5 million for an extended period of time and moving higher as they were in 2003 and 2004.

There’s that socialist miscalculation, and, as I mentioned in part 4, the bizarre description of some weird demand curve that, for some reason, goes vertical at 1.5 million units in a way that I can’t reconcile with either logic or historical evidence.

Of course, lacking a supply-side understanding, and as a result, lacking any curiosity about the subsequent mortgage clampdown, he considers the collapse in construction to be a strong confirmation of the vertical demand curve.

Los Angeles. Wait, Still with Los Angeles?!

He’s still using Los Angeles as the example to prove that housing is a volume cycle, not a price cycle.

I said my piece on this in part 4. One thing I’ll add here is that, as far as I can tell, everywhere else he discusses the “volume cycle” he uses housing starts or sales of new homes. When he discusses Los Angeles he uses sales of existing homes. I may have missed it, but I don’t see an explanation for it.

By his measure, “sales volume” in Los Angeles topped out at 4,000 units in the late 1980s and was even higher at more than 5,000 units in the 2000s.

Figure 2 shows housing permits in Los Angeles. The Fred series just goes back far enough to get a fleeting glimpse of the Los Angeles that was a volume cycle, not a price cycle, 40 years ago.

Ironically, the increased sales volume he’s tracking is correlated with outmigration to places with volume cycles. His chart of existing home sales in Los Angeles shows a decline leading into the 2008 recession. That is when the migration started to slow down and population in Los Angeles started to rise again.

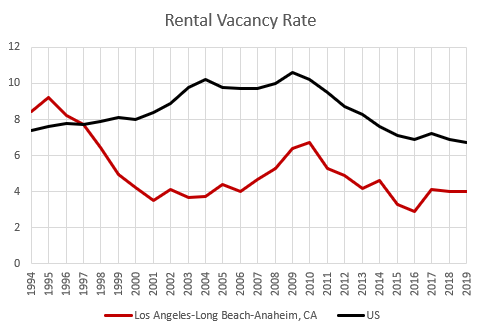

Figure 3 shows the rental vacancy rate for the US and for Los Angeles. Here, also, you can just get a glimpse of the shadows that remained in the early 1990s of the volume cycle that Los Angeles had 40 years ago. I would estimate that vacancy rates of around 10% nationally are the level that will be associated with moderate rent inflation and relatively satisfied demand. It’s definitely above 8%. LA had vacancies in that range when LA had a volume cycle.

Los Angeles rental vacancies now routinely run at about 4%. They did reach above 6% in 2009 and 2010. From 2005 to 2007, population had been declining in Los Angeles. But, with the end of the housing boom (in the rest of the country), population growth popped back up to positive territory - about 1/2% annually in 2008 and after. So, the peak vacancy rate (which was still lower than an adequately supplied market would have) was 4 years after a steep decline in the already pitiful construction rate and 2 years into a population resurgence.

Did the Fed pull back construction that should have happened in LA in 2011 so it happened too early and they had too many homes in 2009 & 2010?

How exactly do you estimate the cyclically neutral production volume in a city whose population growth is negatively correlated with its housing production?

Actually, the socialist calculation is easy when that is the case. MOAR.

You could argue that it is the national production level that matters and that even if LA is short, there is some aggregate level of production that would be excessive in some macroeconomic sense. And that is true.

Maybe you could even argue that LA creates housing supply through displacement rather than construction, and by keeping rates too low, the Fed moved families to Phoenix in 2006 who should have been moving to Phoenix in 2008 when Phoenix could use the growth. There is a cyclically neutral rate of displacement from LA. Since LAs economy was too strong in 2005, it displaced too many people too fast, and so Phoenix was destined to have a recession in 2008.

But that argument is clearly outside Leamer’s frame of reference. He has chosen LA as a self-contained volume cycle. The city he chose as a poster child of the hypothesis.

Leamer writes, “(E)ven with this contrary evidence (that LA had a price cycle when Leamer says housing shouldn’t have a price cycle), I stick with my view that housing experiences a volume cycle not a price cycle, and that 2007–09 was a never-to-be repeated exception.”

He is right that it is never to be repeated. It won’t be repeated because federal mortgage agencies cut their mortgage lending to credit scores under 760 in half and never changed back. We can’t do that again. Both the collapse of already low construction and the collapse of prices in Los Angeles were due to massive blows to incomes and credit. It was a deep, deep demand shock that created a small rise in vacancies in Los Angeles years after a collapse in construction and an upshift in population.

Errors of omission of commission of omission of commission. Turtles all the way down.

Maybe make sure you’re sitting down for this last bit.

Overcapacity

The last section of the paper brings us back to part 1 of this series. It is titled, “Overbuilding in Homes Supported a Workforce Greater than Needed”.

And it begins:

Although GDP and jobs have been growing since 2009, there has been no recovery. A recovery is a period of supernormal growth that gets GDP and jobs back to trend. If anything, we are slipping slightly farther from trend. The critical reason for this, I suggest, is that we have a record number of permanently displaced workers. While recalls that follow temporary layoffs can be accelerated with well designed and well-targeted fiscal and monetary policy, permanent displacements are not much affected by this kind of stimulus. A permanently displaced worker needs new skills, a new location, and, hardest of all, new aspirations.

Today there are many permanently displaced workers in manufacturing and construction… The problem in construction is overcapacity. The number of workers in residential construction has to fit the number of homes being built.

The amount of homebuilding happening in 2015 required only 1.6 million workers, according to Leamer, and there were still about 2.5 million workers in residential construction. There had been 2.5 million residential construction workers in 2001, when Leamer considered construction rates sustainable, and 3.4 million workers in 2006. So, Leamer concluded that about 1 million workers who had been in construction in 2006 were currently employed but unnecessary and another million were just going to have to be permanently out of work. They would need to switch to other sectors. And, he noted that these jobs have a strong “local multiplier” so that the total number of permanently displaced workers “far exceed the 1 million figure”.

By 2015, the “volume cycle” in Los Angeles was maxed out again at less than 3 units per thousand residents. (About 5 or 6 is necessary for moderate population growth. Los Angeles population has subsequently been declining again, since 2017.) By 2013, LA’s rental vacancy rate was back down to 4%. The “price cycle” in LA, measured by Zillow’s typical home value (ZVHI) estimate, topped out at $589,000 in 2006, bottomed at $359,000 in 2012, had risen back to $504,000 by March 2015, and now is $949,000.

Rent inflation had been high, mainly in the Closed Access cities, like Los Angeles, before 2008. Now, its similar across the country, since construction workers became permanently unemployed in every major city. In the years since 2015, rent inflation has accumulated about 20% above general inflation, and it is systematically regressive, so that excess rent inflation in the richest neighborhoods has been negligible and in the poorest neighborhoods has been more like 40%.

I think we could have used a million or two more construction workers.

Residential construction employment, which Leamer thought was bloated by nearly 1 million workers in 2015, has just kept going up. It is now nearly back to the 2006 peak. Leamer thought we only needed 1.6 million construction workers in 2015, but now we have 3.4 million. Does he think we have a million workers more than necessary now?

A post from UCLA about expectations in the housing market in October 2022 cites Leamer’s 2007 address and 2015 update as the evidence of Leamer’s expertise on housing and the business cycle. Then it references Leamer saying there’s been a chronic housing shortage for more than a decade. “We are not overbuilt by any definition.”

That seems like it would have been news to Ed Leamer less than a decade ago in 2015!

I wonder what he would write today in lieu of the 2015 paper. Does he think the shortage is a post-2008 phenomenon that doesn’t change anything about the positions he took in 2007 and 2015? Has he reconsidered anything?

Unfortunately, as for the audience, I think he could write exactly the same words today, and it would be broadly met with approval.

When We Lost Our Minds:

Part 2: Respecting the Timeline

Part 3: The Dog that Didn’t Bark - Retirement Homes

Part 5: The Lessons Leamer Learned

Thanks for this series, particularly this final chapter. What's ironic is that the U.S. seems to have achieved the state of unity in the housing market that Leamer and others were incorrectly using to describe the U.S. in the early 2000's. Our equilibrium is permanently low supply, bad filtering, high rents, and reduced migration rates. I'm exaggerating a bit, but the demographic impacts of housing costs since the Great Recession are a matter of fact---which is now being described incorrectly by a new generation of economists and pundits.

Leamer #1 Only half right (and not the right half :)) Housing is the sector _most affected by_ monetary policy. There is no "business cycle" and therefore housing does not predict it, does not cause it. Economic fluctuations result from the interaction of non-monetary events and central bank actions.