Conor Dougherty is one of our best housing journalists. His book “Golden Gates” is a cornerstone of YIMBY literature. And he wrote an article in last week’s New York Times about housing in Kalamazoo, Michigan that I found to be confused and frustrating.

Before we get into that, I need to back up and review the recent history of housing in Kalamazoo. It’s a big story. And, remember - big stories are simple stories. (Why did New Orleans depopulate in the summer of 2005? Why did San Francisco boom in 1849?)

Kalamazoo Housing Trends and What Didn’t Happen

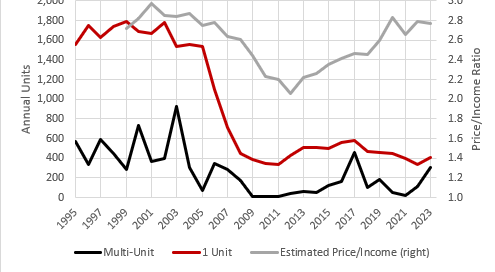

The story of Kalamazoo housing is the story of housing in countless cities across the country. Everything was normal and fine before 2008. As Figure 1 shows, there was no building boom in Kalamazoo in the 2000s. There was no price bubble. Then everything collapsed. First housing starts, then prices, then foreclosures.

Rents didn’t decline much, but eventually, after the market bottomed, rents started to rise at an unprecedented pace and the recovery in home values after 2012 has been entirely due to rising rents. Rents are rising because home building in Kalamazoo largely shut down. Today, as a proportion of incomes, home prices are similar to what they were before 2008 in Kalamazoo, but rents are much higher.

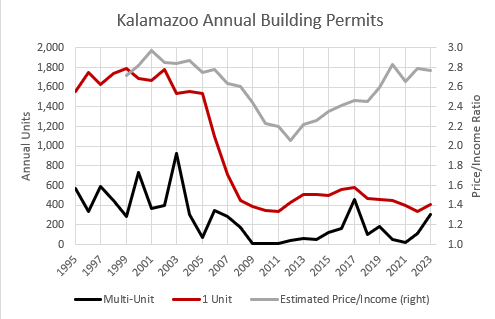

Kalamazoo doesn’t have enough ZIP codes to reliably describe their housing market using my Erdmann Housing Tracker model, but in Figure 2, I just tracked home prices across Kalamazoo based on the average and the standard deviation of prices across the 15 ZIP codes with data. Again, this is the pattern in countless cities across the country. The average home price/income ratio, shown in Figure 1, that declined from 2.8x in 2006 to 2.1x in 2012 reflects an asymmetrical outcome.

The high end basically was flat, and the low end lost more than 50%. Figure 2 shows the average home price, and prices at the high end and low end of the Kalamazoo market, since 1999, indexed to 1999 (and adjusted to average income growth over time).

The conventional wisdom about the crisis is that there was an out of control credit bubble that drew in unqualified borrowers and speculators, which drove prices to unsustainable levels, and led to a building boom that left us swimming in a glut of housing.

I have shown that this story is wrong in some way everywhere. But in the countless cities like Kalamazoo, the story is especially hallucinatory. Neither prices nor construction had increased. There was no boom in Kalamazoo to attract optimistic speculators. Homeownership was no higher in 2005 and 2006 than it had been in 2000. It is a story that depends on the interaction of about a half dozen presumptive facts and not one of them is real.

But, the conventional approach has been to act as if this massive dislocation was inevitable in Phoenix and Orlando, and so there must be a reason it was inevitable in Kalamazoo, too.

Also, as Figure 3 shows, Kalamazoo was not a city in decline. Population was growing slowly. And, Kalamazoo was permitting housing at a higher rate than the national average. Then, there was a cyclical slow-down in housing construction that should have reversed by 2008, but instead was beaten to the ground permanently.

And, again, this is common in countless cities: construction started to slow down years before the 2008 crisis. The vast pile of careless literature on this issue imagines that cities where prices hadn’t spiked higher, like Kalamazoo, must have, instead, had unsustainable building booms. But in cities like Kalamazoo, building had slowed down well before the crisis hit and well before home prices collapsed disastrously.

In nominal terms, according to Zillow, the typical home value in Kalamazoo peaked at the end of 2006. It had only declined by about 5% when the financial crisis blew up in September 2008. Eventually, the typical nominal home price would bottom out at the end of 2011 about 18% below the 2006 peak.

The price collapse happened well after years of collapsed building activity. To attribute the price collapse in any way to “oversupply” is a gross misunderstanding.

So, what happened to Kalamazoo?

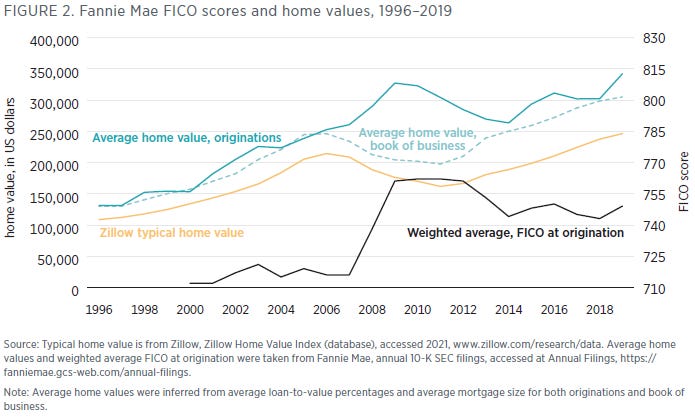

It’s a big, simple story. The private mortgage markets which had attained an important amount of market share from 2004 to 2006 completely dried up by mid-2007. Instead of moving in to stabilize lending, federal officials both informally and formally turned the screws on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac so that conventional lending to homebuyers which had been served by Fannie and Freddie for decades, since well before the subprime boom, was cut off.

As I have noted before, the average credit score on approved mortgages jumped by 40 points between late 2007 and late 2009, both across the whole market and within Fannie Mae. Over the course of 2008, more than half of the mortgage market below credit scores of 760 was cut off (Figure 4).

Before 2008, the average price of homes that had previously received Fannie Mae mortgages and homes that received new Fannie Mae mortgages had been holding steady at about $250,000. By 2009, the average value of homes across the country declined by about 20%, and homes with Fannie Mae mortgages also declined by about 20% - to about $200,000.

But the average home that received a new Fannie Mae mortgage in 2009 was valued at about $327,000.

Imagine how much lending dried up in Kalamazoo where, in 2007, average home prices in 15 ZIP codes had ranged from about $85,000 to $200,000.

Through direct control and regulatory clamp downs, the federal government wiped out most of the homebuyer market in Kalamazoo.

It wasn’t a spike of defaults from unqualified buyers that got in over their heads that collapsed the market. The rug got pulled out. There suddenly weren’t any buyers because they were newly obstructed from access to credit that had been available for decades before.

That’s it. That’s the thing that happened. That, all by itself, can explain the major changes in Kalamazoo housing from before 2008 to after 2008. And no other explanation remotely matches the evidence.

It’s a big, simple story.

What’s Conor Dougherty Have to Say?

Dougherty’s article is titled, “What Kalamazoo (Yes, Kalamazoo) Reveals About the Nation’s Housing Crisis”. Dougherty has a deep understanding of the politics of housing, which he has been developing for decades. And, he even understands that tighter lending standards are part of what has changed. But he doesn’t understand that it is the story, in a place like Kalamazoo.

It’s understandable that he doesn’t understand. He could have read all the popular books on the crisis, all the most cited academic literature, talked to all the big names, and it wouldn’t have been particularly noted.

The thing that happened - the nuclear bomb that was dropped on Kalamazoo in 2008 - is largely ignored. It is assumed to be part of the correction process of returning back to normal after the subprime boom. But it was an additional, novel shift in standards, and it was extreme.

So this creates a problem. Anyone trying to explain the Kalamazoo market with this giant hole in the middle of their explanation will be left only with bad conclusions - either conclusions that are empirically false, poorly reasoned, or implausible.

It might seem like I am going to be shaming Dougherty. But, what else could he do? The only choices are to ignore the entire literature on the subject and rewrite the history as I have done, or plod around in confusion.

He’s writing for a Ptolemaic, geocentric audience. He can’t describe the earth orbiting the sun. He has to describe how Kalamazoo fits in the various epicycles. He’s writing for an audience that doesn’t know about microbes, and he has to explain why they are all getting sick. It would be impossible to get it right.

As I walk through the many claims from the story, think about the causal density here. It starts with an empirical blind spot. Then, the holes left by that blind spot get filled with other explanations. Then, those explanations inform other conclusions and other attempts at factual claims. Then those claims add up to create a gestalt view.

My dilemma is that the observational error is huge and obvious. But, the effort required to acknowledge it is just too great, because changing that one fact changes a hundred other presumed facts.

The main impediment to understanding the housing market is knowing too much. Dougherty knows a lot.

The Details

It starts with the subtitle.

A decade ago, the city — and all of Michigan — had too many houses. Now it has a shortage. The shift there explains today’s costly housing market in the rest of the country.

Kalamazoo was a moderately growing city. It grew by 5% from 2007 to 2014. During that 7 years, building was negligible - about 1.9 units per 1,000 residents annually. As a point of comparison, the Los Angeles metro area has a slightly lower population than it had in 2011, and it has averaged 2.1 units per 1,000 residents over that time.

The subtitle is remarkably off base. There weren’t too many homes. There were plenty of families requiring tenancy. It had suddenly become illegal for many of them to own them, and so the market was in disarray.

There is a simple and clear explanation for the appearance of a glut. But there was only the appearance. There weren’t too many homes. There was a lack of families with permission to be owners.

The descriptive text of the header picture.

Kalamazoo, Mich., got walloped by a foreclosure crisis in the early 2010s that left many of its neighborhoods with overgrown lots where ramshackle houses had been bulldozed.

Following the implausible subtitle, this seems like it follows. Naturally this would be the result of having too many houses.

What if there weren’t too many houses? What a strange and horrible thing to happen to a city - tearing down its homes. Ripping holes in neighborhoods.

Think of how motivated you would be to find an explanation if you didn’t have the supply glut as a satisfying and wrong explanation.

See how the lack of one fact already is sowing presumed facts which will then lead to other conclusions and presumed facts? And we aren’t even to the body of the article yet.

Rent vs Price

There is a lot to unpack in Dougherty’s treatment of affordability. So, first, I need to carefully note what has changed in Kalamazoo.

Notice in Figure 1 and Figure 2, relative to incomes, home prices are not any higher in Kalamazoo than they were before 2008. The reason Kalamazoo hasn’t built many homes since 2008 is because the existing homes have been too cheap.

And, since existing homes are too cheap, few new ones are being constructed. And, so rents are rising.

Among the 15 ZIP codes in the Kalamazoo metro area with Zillow price data and IRS income data, in both 1999 and 2007, price/income ratios ranged between 2x and 3x. Very affordable. Then, prices collapsed at the low end when mortgage access was cut. Price/income levels averaged about 2x all across the metro area after the mortgage crackdown. In the richer parts of Kalamazoo, price/income was still 2x because the residents were buying homes like they always had. In the poorer parts of Kalamazoo, price/income fell from 3x to 2x because the tenants weren’t allowed to buy them any more.

And, by 2021 (the last year with IRS income data) price/income levels were back near the pre-2008 levels - from 2x to 3x. Some ZIP codes have bumped up toward 3.5x. But, this is a very affordable market. There is no reason to call this an affordability crisis for buyers.

On the other hand, rents didn’t decline much after 2008, but recently rents have been rising sharply. From 2014 to 2021, Kalamazoo incomes rose by about 42%. Core CPI inflation over that time rose by 20%. Rents in Kalamazoo rose by 53%.

This is not because they have built nicer homes. They are hardly building any. As in much of the country, rents are going up on the existing stock of homes.

And, as I have documented, rents are going up much more in poorer neighborhoods than in richer neighborhoods. Zillow doesn’t have a breadth of rent data in Kalamazoo, but everywhere that rent inflation has been 53%, it has been more like 30% in the richer neighborhoods and 70% in the poorer neighborhoods.

Residents in Kalamazoo have two problems - high rents and a government that prevents them from buying affordable homes. They don’t have a price problem. They don’t have an income problem. They have a highly regressive rent problem.

Prices need to be higher for rents to be lower.

The article begins well.

In her State of the State address this year, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer lamented the housing shortage and landed one of her biggest applause lines with, “The rent is too damn high, and we don’t have enough damn housing. So our response is simple: ‘Build, baby, build!’”

This is a coherent description of the problem and the solution.

But, then Dougherty moves to discussing programs to subsidize households with 6-figure incomes to help them purchase homes.

He profiles a family with a 6-figure income that moved to Kalamazoo in 2016 and bought a house for $170,000. Then they also bought an investment property. Their home has doubled in value, and Dougherty treats this as evidence of a city that has become unaffordable.

He also notes that the city has to keep increasing its budget for homeless support because rents are going up so much.

These are two very different problems! That family bought a home for about 1.5x their income and it has now risen to about 2.5x their income. That is exceedingly cheap in both cases. The doubling of the home price was a return toward normal!

The rents for homeless families are not returning to normal. They were never low. They are rising to unusual highs. The section ends with a lament from the homeowner that she is happy that her house gained in value but, that she works with the Kalamazoo County Housing Department, where “I’m trying to solve the reverse problem, which is nobody can afford a house.”

But, these two trends are not in tension.

Renters have an affordability problem. They have an affordability problem because homes in Kalamazoo are too cheap. This sounds incoherent if you have a blind spot where you aren’t looking at the Kalamazoo market through the lens of the big simple story of mortgage suppression. In 2008, the federal government put controls in place to prevent Kalamazoo renters from buying a home where it would be advantageous to them. So, it is becoming increasingly disadvantageous to be a renter in Kalamazoo because the renters can’t resolve the problem by buying.

Again, this is the story all across the country. One trend that I have found is that, systematically, and to an extreme, where home prices fell the most after 2008, rents have risen the most since then. That is a really weird pattern to see. It is easily explained by the imposition of extreme mortgage suppression in 2008. It is highly confusing to any narrative that doesn’t center that fact.

The Reverberations of the 2008 Crisis

Next Dougherty discusses a family whose landlord sold the unit they were paying $630 rent for, who had to move into a place renting for $1,500. (Did they look into buying? Why didn’t they buy?)

He ends the section with an elegant description of the desperate problem the US finds itself in.

For all its housing price inflation, Kalamazoo is still so much cheaper than other parts of the country that it was recently named one of America’s most affordable cities for professionals. A darker way of putting it is that Kalamazoo is the final stop in the housing crisis. And that’s the problem with being a place where people move to feel richer: Those who get priced out have no place left to go.

And he, correctly, writes about how a functional housing market works, which is that ample new homes are constructed so that old, aging homes become affordable. That isn’t happening.

He writes:

Builders aren’t putting up suburban subdivisions at the rate they once did.

For one thing, developers everywhere find it harder to raise money, and homeowners find it harder to get loans. That’s because banks and the government, in a quest to prevent another housing bubble, have raised lending standards and made mortgages harder to get.

Builders have also become more cautious since the 2008 crisis. Many moved away from off-the-shelf (“on spec”) homes, and now they prefer that customers pay for properties before they’re built.

Land developers — companies that take a piece of dirt and add basic infrastructure like streets, plumbing and power, creating the lots where new homes are built — have also cut back. The number of vacant developed lots, or places where a homebuilder could start construction tomorrow, is still 40 percent below its pre-Great Recession level.

He cites the tightened lending standards, but since he doesn’t realize that that is the story - the whole story - he is left to fill in the blanks with these common descriptions of changes in the marketplace. Why aren’t builders building spec homes? Why aren’t land developers bringing new lots online? Because the mortgage crackdown made existing homes in Kalamazoo cheaper than new homes. Developers don’t create product where there isn’t a market.

This is common in the conventional discourse. Pundits end up putting an implausible amount of weight on the presumed change in sentiment among the producers. As if buyers might be lining up to buy homes as they were before 2006 in Figure 1, and developers are just too gun-shy to take their business.

Sophisticated economists trying to fill in the big gaps in the story of post-2008 housing will claim that the lack of construction is due to market power of the large builders. They claim that they purposefully slowed down construction because they saw how bad oversupplying the market was before 2008 and so they collectively are avoiding repeating that fate. This post is too long to go into the details on that, but it’s another example of how ridiculous the claims can become that are available to fill the knowledge gap with when you can’t observe the truth.

The Wrong Solutions

He writes:

The idea of a truly free housing market, where private developers work to satisfy the demands of families that acquire homes through their own grit, has always been a fiction. From the G.I. Bill to government-backed mortgages to the generous tax breaks afforded homeowners and developers, housing is one of the most subsidized sectors of the economy — arguably the single most, if you consider that land derives much of its value from its proximity to public services like roads, parks and schools.

Housing has a big mix of taxes, tax deductions, subsidies, regulations, and funding coordination. It isn’t true that it is grossly over-subsidized. For a start, homeowners pay a pretty hefty property tax. In Kalamazoo it runs about 1.6% of home value, annually. That might not be so true in Dougherty’s home of California, but surely Dougherty would blush at the thought that California’s problem is that the free market is unwilling to provide ample housing in spite of the government’s efforts to support them.

Also, Kalamazoo has little value derived from proximity to amenities. Mostly, in Kalamazoo, the cost of a home is the cost to build the structure. In fact, you could say that the reason homes aren’t being built there is that the land has negative value. The cost of a new home is higher than what you would have to pay for the same home bundled with an existing lot. If that wasn’t the case, they would be building more homes.

Understand me. I am not saying that living in Kalamazoo has no value. I am saying that the government won’t let people who value Kalamazoo make an arrangement with their banker to buy a piece of it. But even before the mortgage crackdown, home prices in Kalamazoo did not include significant amenity premiums. The downward filtering created by ample new construction generally kept land a small part of the cost.

Additionally, in his own reporting, he claims that the market in Kalamazoo provided so many homes a decade ago that they couldn’t give them away. They had to bulldoze them for lack of takers.

Even today, there are countless homes for sale for less than $200,000. I sometimes point out how, before interest rates increased, it was common to find homes across the country whose rent was well above the mortgage payment it would take to buy the same home. That was the case because the government wouldn’t allow those tenants to get mortgages. They aren’t allowed to make their own economic decisions.

That is still the case in Kalamazoo. If you click on a random house in Zillow, the estimate of the monthly rent on the home will likely be much higher than the estimate of the mortgage payment required to buy it.

The truly free market isn’t the problem. The CFPB and FHFA are.

“So the market is not working,” Mary Balkema said as she drove me through Kalamazoo’s impoverished north side. And if you want the market to work, she continued, the government has to be the catalyst.

Hulk getting angry.

Then Dougherty describes Balkema showing him various new homes around the city, and explains that they usually required subsidies of around $100,000 to get them built.

Yes! The existing homes are too cheap! That’s why you can’t profitably build one there. But, to a developer, everything looks like a cost problem. If buyers can’t get funds, it looks like your costs are too high.

The question to ponder here is why are homes selling at prices so low that builders can’t build profitably if rents are at record highs? They were building and selling a lot of homes in Kalamazoo before 2008. What changed? WHAT CHANGED?

Dougherty says that the housing cost problem has even reached the upper-middle class in Kalamazoo. He blames it on rising construction costs since 2020.

Oh, excuse me? Was construction booming in Kalamazoo in the 2010s when inputs were cheap and builders were desperate for work? Again, this is just filling in the blanks with wrong stories that seem to fit. As I noted above, even at today’s interest rates, Zillow residents can generally lower their housing costs by buying instead of renting. Builders stopped building starter homes because the mortgage crackdown cratered the market for existing homes.

Dougherty squares that circle by believing there was a housing glut in the 2010s. Filling one hole in the narrative with the wrong answer makes it seem believable to fill another hole with another wrong answer.

Also, there is now a burgeoning resurgence of a starter home market in markets where rents have risen high enough for them to pencil, but it is dominated by build-to-rent neighborhoods. Before 2008, the last time those neighborhoods were constructed in any significant number, they were sold to homeowners. Why? WHAT CHANGED?

Dougherty points to Michigan’s attempt to solve the problem, which is to subsidize developers to build middle class housing and to raise the income threshold that renters must be below in order to live in subsidized rentals.

That’s all well and good. Supply is supply. But it is a misunderstanding of the problem. Middle class families don’t need handouts to get affordable housing in Michigan. They need permission to buy, so they can outbid the current buyers and pay enough to make new building profitable.

It wasn’t so long ago, Mr. Dame told me, that developers in Portage made money building housing for the kind of people who will live in the new subsidized project. Now a good amount of his job consists of having developers tell him that the financials on their next project have blown up and they need help.

“Every project that’s coming forward now is asking for some level of government assistance,” he said.

The prices are too low.

The article ends with the story of another couple with a six-figure income who were chosen to get a rental unit in a new subsidized “work force housing” project that would rent for $1,700 a month.

I would love to know why this family is renting. I suspect the CFPB and the FHFA have something to do with it. It’s the sort of question a curious reader might ask. The article doesn’t say.

The article ends with a quote from the father of that family, “It’s like there’s no middle class anymore.”

Being middle class has traditionally been associated with homeownership. If you wonder why it died, try filling out a mortgage application these days.

It turns out that a generous lending market creates a progressive externality. It lowers the rents on units that renters live in. Now that we are 16 years into the natural experiment which has proven that, it’s long past time to end the experiment.

But the lack of understanding about it runs so deep that even YIMBYs most informed and most respected leaders and writers will be incapable of advocating for it. At least Vice President Harris, Governor Whitmer, Dougherty, and the local officials he profiles are, thankfully, focused on a “Build, baby, build” mentality, but the foundation of misunderstandings it is built on could easily be toppled.

Voters think Wall Street developers are crowding out real families from the housing market. The new rental homes aren’t popular. Developer subsidies aren’t going to be popular. There are many voters and lawmakers who would shut it down today.

And, in the meantime, in any case, we will be throwing money at attempted solutions, left and right, while the only effective solution is to simply remove the fetters we have placed on mortgage lenders.

About 70% of Kalamazoo’s new home buyer market has been obstructed now for 2 decades. It is a naturally occurring source of supply if we allow it. It is an imposing gap to fill if we don’t.

Dougherty sort of helped write a conclusion to this post with a clarifying tweet. He wrote:

There are those really expensive cities where land/regulation drive a lot of the cost. Then there are those places where they need higher rents TO COVER THE COST OF THE BUILDING. Financially speaking, the first one is a lot easier to solve, though obvs it takes political will.

Figure 6 is excess rent inflation in Kalamazoo since 2015. It accumulates to about 20%. That’s 20% more than the rise in the general price level. That’s more than 2% annually, above general inflation. In Kalamazoo’s poorest neighborhoods, rising rents are almost certainly causing real disposable incomes to decline, year after year.

Rents are much higher in Kalamazoo than they have ever been. But prices are similar to where they were before 2008.

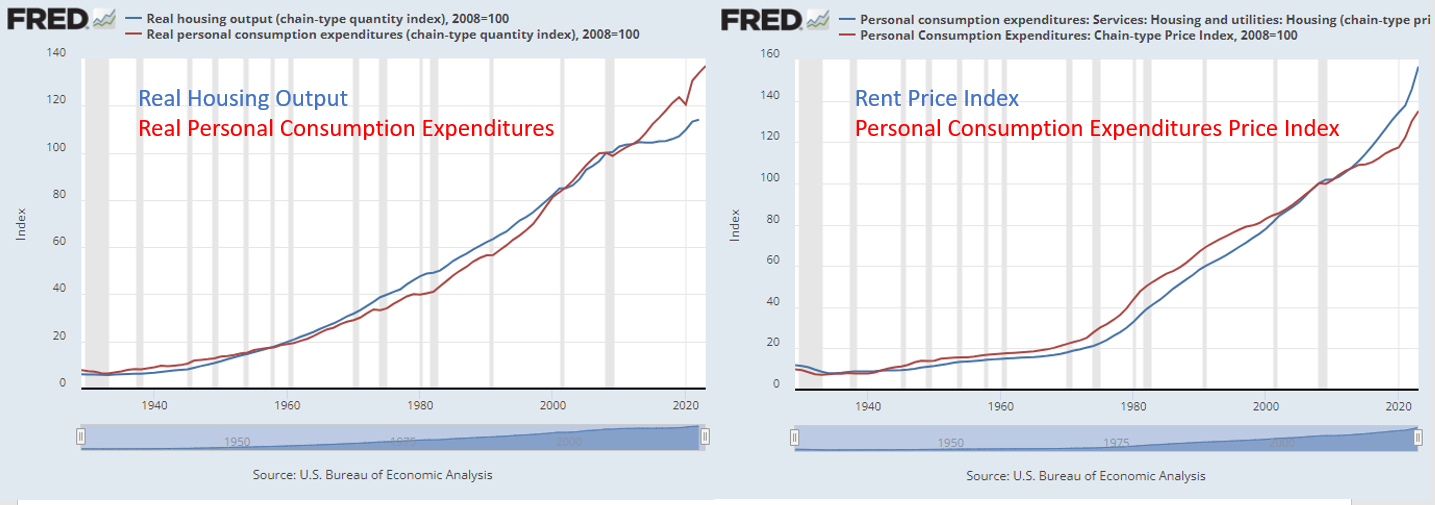

Why, now, in 2024, do rents still need to rise higher? Figure 7 contains charts for U.S. real output and for price inflation for rents compared to all consumer expenses.

Since 2008, the growth of real housing flatlined. The real housing stock has expanded by about 20% less than the real value of other goods and services. And rents have been inflated by about 20% more than prices of other goods and services.

It is true that if Conor asks a local developer in Kalamazoo, “Why can’t you build this project?” They will accurately say, “The rents aren’t high enough to justify the cost.”

But, isn’t that really weird? We are at the end of an unprecedented period of low construction activity and high rent inflation. It has never been this bad before. Conor is relating the experience of those developers accurately, but how in the world could it be the case that in 2024, our problem is that we don’t have enough rent inflation?

The right question to ask is, “What happened in 2008 that suddenly created an extreme shift in the trends of construction and rent inflation?” The answer to that question is that we legally barred millions of households from being mortgaged housing producers. This is “What Kalamazoo Reveals About the Dangers of Incomplete Observation”. The most important observation about 2008 is buried under piles of literature which was the manifestation of a moral panic about mortgage lending. We have to unlearn the moral panic to be able to see the elephant in the room. We made reasonable mortgages illegal, and that basically explains everything. That is the Hurricane Katrina in the middle of our housing dilemma. And if you can’t see it - if you are blinded by the moral panic, as so many understandably are - then you will find yourself in the midst of a devastating rent inflation crisis calling for more rent inflation.

What changed in Kalamazoo is that before 2008, about 1,000 households each year would reasonably decide that buying a new home made sense. Maybe, like today, their fixed mortgage payment would be lower than their floating rent payment would be. Those households became suppliers. How much does it cost to build a new home in Kalamazoo? Whatever it was, they would pay it. Quite regularly, year after year. About a thousand families would do it that can’t do it today.

Those new homes kept rents low in Kalamazoo. Why do builders need higher rents today to build the same homes? Because the historical buyers of those homes aren’t in the market any more. They can’t be producers any more. The potential owners of those new homes who say they don’t “pencil” because the rents aren’t high enough would have said the same thing in 2005. They weren’t buying homes in 2005 either. Families were buying homes. They “penciled” for those families. They would still “pencil” for those families if we let them get mortgages.

And if we let them, rents in Kalamazoo would, blessedly, go down. The market would do that. The government couldn’t possibly get us back to that level of affordability. Conor Dougherty, following the conventions of our time, has it frustratingly, devastatingly, wrong.

Just try to imagine the injustice and financial stress, both public and private, that would be endemic in a country where our ongoing housing policy in Kalamazoo is to keep rents higher than most families that live there can afford, by funding it with public subsidies.

"There is a simple and clear explanation for the appearance of a glut. But there was only the appearance. There weren’t too many homes. There was a lack of families with permission to be owners."

This is a great insight. The core of your argument, that low income buyers aren't "allowed" to be buyers is also brilliant. I think it even applies to California markets like Irvine. The ripple effects limit housing buyers for both expensive and inexpensive properties, keeping rents high for existing stock.

Really a brilliant piece of writing!

Hi Kevin,

I've been an avid reader of your content for about 6 months. I've been confused about something for a while, so I figured I'd ask.

For a builder, what is the difference between selling to a landlord who rents out the property for say $2,000/mo, and selling to a home buyer who will pay $2,000/mo in a mortgage? Why didn't builders immediately pivot to build-to-rent after the mortgage shutdown? After the crash, why did rents have to rise in order to make build-to-rent feasible, when build-to-sell was already feasible beforehand?

Thanks so much!