Patterns in housing: Big = Simple

Here are a couple of charts that provide a sort of mental benchmark for the scale of our housing supply problem.

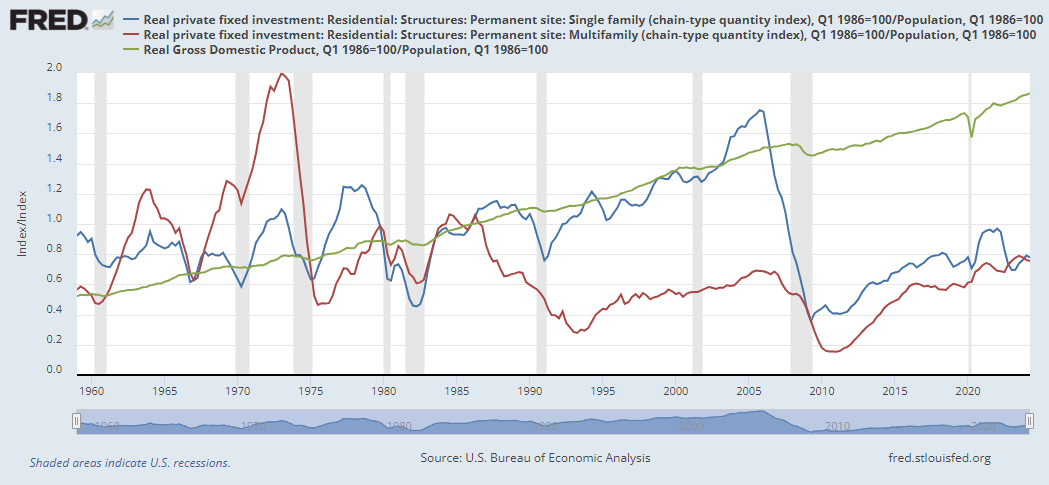

Figure 1 is real GDP (green), real investment in apartments (red), and real investment in single-family homes (blue) since 1959.

You can see the effect of mid-20th century downzoning on apartment construction. This was a relatively universal development across the country, and until 2008, local housing conditions mostly depended on a metro area’s ability to substitute exurban single-family homes in place of more dense infill development that had been regulated away.

Figure 2 shows the same measures on a per capita basis.

Maybe the best way to see the permanent collapse in each home type is to show them both as a ratio with GDP (Real single-family investment/Real GDP <blue> & Real multi-family investment/Real GDP <red>). In Figure 3 both ratios are indexed to 1986=100.

Before the 1980s, there was a baseline minimum amount of homebuilding, with building booms on top of it - mostly in multi-family. Since then, there is no building cycle. There is just the baseline amount of homebuilding, from which multi-family dropped permanently in the mid-1980s and single-family dropped permanently in the mid-2000s. The permanent collapses both look like the downward portion of a cycle, and are generally described as such, leaving many to bemoan our overly cyclical construction market.

I think there are a few interesting notes here.

I have been writing a bit about how micro-level experience frequently misleads about macro-level trends.

One ongoing theme in my work is that the economy is hopelessly complicated. We can’t begin to understand it, and for the most part, on marginal details, it’s not even worth trying. But big stories are simple stories. The bigger the simpler.

Figure 4 is a graph of employment in New Orleans. This graph has a thousand complicated stories and 3 simple stories. You can tell they are simple because they are so big.

Figures 1, 2, & 3 have a similar issue as Figure 4. All those squiggles up and down in, say, single-family housing from 1959 to 2006 are really complicated. So complicated they aren’t worth understanding unless you work in a specialized job that requires always making your best guess about it. And your guesses about what squiggles are coming next will only slightly help, in practice.

But there are two big things that are hard to miss in those charts. A big, permanent drop in investment in apartments after the 1980s, after the last big round of 20th century downzoning, and a big, permanent drop in single-family investment in the 2000s, with the big shock to mortgage access. They are so big and so permanent that the complications become noise. They are big stories, so they are simple stories.

But, since so many experts in housing are engaged in the daily complications, they have an outsized sense of the importance of the complications. Hurricane Katrina announced its arrival, so reformers in New Orleans in November 2005 didn’t endlessly deflect. “Sure, the Hurricane is a factor, but there are a lot of reasons New Orleans is having trouble.” They might have still considered the complicated issues important. And they might have even considered the shock of the hurricane to be an opportunity for reform. But, we didn’t need to have endless debates about whether there had been a hurricane, and where all this water could have come from.

On the other hand, quite a few people still manage to believe there is not a housing supply crisis. And the best industry experts we have in housing will frequently agree that zoning is a big problem, but it’s just one more problem along with labor costs, changes in tax policies, etc. The Reagan tax bills are a popular touchstone for changes in apartment construction in the 1980s. And, in fact, the Reagan tax bills are probably responsible for some of the bigger squiggles in the 1980s. At some scale, you could probably categorize the Reagan tax bills as a big, simple story. Sort of Hurricane Ida to the Hurricane Katrina of downzoning.

I think one issue is visibility. A true thing you could say about housing is that we lack abundant housing because we don’t have self-organizing drones that can absorb key elements from the air, build all the supplies they need on site, and complete a house in days.

That’s a true story. That is a reason we don’t have more affordable housing. But it’s not worth writing papers about it, because the solution isn’t possible.

You could say the same thing about building an apartment in Pasadena or building large numbers of single-family homes that buyers with 690 credit scores would find attractive to buy. We basically can’t do those things either. They are also reasons why we lack abundant housing. But, for a typical developer or builder, there is no point wasting time imagining that we could.

Insiders and developers don’t waste time trying to do things they know are impossible, even if it is ridiculous that they are impossible. They spend all day looking for workers, negotiating loans, arranging inspections, and figuring out idiosyncratic local tax rules. They know those things are important because everyone in the business spends all of their time on them.

Anti-apartment zoning or the federal mortgage clampdown may be important, but those are assertions from abstractions. Maybe households with 690 credit scores would buy a lot more new homes if they could get mortgages. But how could we know for sure? On the other hand, I know that, say, my lumber costs just went up 20%.

So I think there are two issues that work against an honest and full-throated public reckoning about the housing shortage. There is a natural inclination to think that big problems are complicated problems. And, when a simple problem is so big that it becomes binding, it can actually become harder to notice.

You say the dodo bird is struggling? I haven’t seen any dodo bird poaching for years.

I liked a description you had a few posts back about how legal restrictions make potential building sites "infinite cost" for certain locations. For homeowners that's the most wonderful thing in the universe---if they own single family zoned property in a desirable neighborhood they have an investment that beats all stock markets, bond markets, precious metals, crypto, etc...

And they will vote to keep it that way.

here's a thought that I don't have a platform to promote, so feel free to use yours Mr. Erdmann.

We need a nationwide housing building initiative, on the scale of the WPA from the 1930s. This would accomplish two complementary outcomes. 1) It would create lots of new housing supply which will eventually drive down prices. And 2) It will offer jobs to the younger millennials and GenZ who complain that they can't find good jobs, giving them both consistent employment and valuable skills. No, Brianna, not everyone gets to work in Marketing. You may need to get dirty in the landscaping department. But at the end of perhaps a 10-year initiative, we'll have significantly reconciled the housing and skills gaps, for far less than the cost of education at universiites.

We could call it the "Civilitary" and recruit like the military does. Sign-up bonuses; 6-week boot camp; then a 2-3 year stint working on building out infrastructure & housing & associated work in the middle of Pennsylvania or down in Alabama or out near San Francisco or Portland or wherever. Sign on for long enough, you could end up with a pension that helps pay off the housing that you helped build. Can you imagine the pride and sense of accomplishment that would come from that?

Plus, just think what we could do if we could figure out how to build a 2-bedroom apartment unit for $80k, which is ridiculously overpriced just from back-of-the-envelope calculations. Pay that off in 10 years ($8k principal / year), and in about a decade and a half we'll be drowning in affordable housing.