Home Price Trends Point to a Worsening Lack of Supply: Part 2

Post GFC: Under-priced and under-produced housing

In the previous post, I outlined the evidence that rising housing costs, pre-Great Recession, were driven by localized supply constraints that are so binding that any cyclical increase in housing demand leads to economic displacement from New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. This creates the strange outcome that more homebuilding in those cities is associated with lower population growth.

Policy decisions during and after the Great Recession were driven by the myth that housing had been overbuilt and that excessive demand (through reckless lending, irrational speculation, artificially low interest rates, etc.) had been the culprit. So, the local supply constraints that turn a housing boom into a domestic migration crisis were really not addressed at all. Policy changes were all associated with the moral panic around mortgage lending, to drive down demand for homebuying.

The demand for shelter was naturally occurring and inadequately met before 2008, which is why there was a domestic migration crisis and a home price spike. Demand for shelter temporarily declined as a side effect of the negative income shock of the recession and the foreclosure crisis that followed. But, generally, when prices (reflecting the shock to buying power) declined, rents (reflecting demand for shelter) remained relatively level.

Figure 11 demonstrates what happened. In most cities, in 2005, housing markets were operating in a generally functional context where supply constraints weren’t completely binding. Rising demand for shelter was met with new construction. Rents (light blue in the hypothetical Figure 11) and prices (dark blue in Figure 11) were at the level required to induce marginal new construction, as on the left panel of Figure 11.

When the demand shock was imposed on home buying, it lowered home prices everywhere. Rents were relatively stable because the demand for shelter mostly remained. By 2012, the relative prices of homes had been driven significantly down. This was especially true where incomes were lower and households are more dependent on generous credit markets.

In paper #3 of this series, I discussed how supply constraints were the primary reason for rising prices and the demand shock that lowered prices after 2007 was largely unrelated to that. There was a bit of a credit boom and bust, but it was relatively small compared to these other factors.

In Figure 12, I compare LA, Phoenix, and Atlanta, to recognize the various factors that were moving home prices up and down. Of these 3 cities, the only one where low tier prices greatly outpaced high tier prices before 2008 was LA. That is the process of economic displacement that I laid out in the previous post. Lending and speculation are only tertiarily related to this. That price differential is required, because of the lack of adequate building, to motivate existing residents to choose to be displaced from the region. Somebody has to be displaced, and the displacement is achieved through rising housing costs, which tend to pile up the most on the poorest residents. That bump in LA in Figure 12 is due to supply constraints.

Prices across the entire region of Phoenix appreciated before 2008 because it was overwhelmed by the housing refugees flooding out of Los Angeles. Neither high tier or low tier homes in Atlanta experienced particularly unusual trends before 2008.

In all three cases, prices dropped significantly after 2007. And, in all three cases, low tier prices, which are more sensitive to credit conditions, dropped much more than high tier prices. In Phoenix and Atlanta, where low tier prices had never risen much higher than high tier prices, this left cumulative low tier price changes by 2012 much lower than high tier price changes.

This was a universal trend, as you can see in Figure 13. Taking the whole boom and bust into account, from 2002 to 2015, home prices where local incomes were lower increased less than home prices where incomes were higher. I used 2015 as a turning point because that happens to be when Zillow starts publishing rent data at the ZIP code level which plays into this analysis. But, you can see in Figure 12 that by 2015 there had been some recovery. The relative decline in low tier prices was even worse over the period from 2002 to 2012.

So, looking back at Figure 11, the center scenario of underpriced homes was especially true of ZIP codes where average incomes were low and cities where average incomes were low. Being at the center scenario of Figure 11 means that homes are priced too low to induce new construction, and so, after the housing bust, construction rates in the cities with the lowest incomes declined the most (Figure 14).

Before 2008, we had the peculiar problem that the richest cities built the least. (Moving all the poor folks out turns out to be an effective way to raise average local incomes and make your city appear richer.)

After 2008, construction in poorer cities declined, to be more like the housing deprived cities. As I document here at the Tracker, this is because the credit shock drove prices down by well over 10% where credit was now limited. The lower that local incomes were, the deeper into the center scenario of Figure 11 you went.

Well, what happens if homes are too cheap to build new homes? Rents have to rise until prices are high enough again to induce new construction again. This happened to a staggering degree.

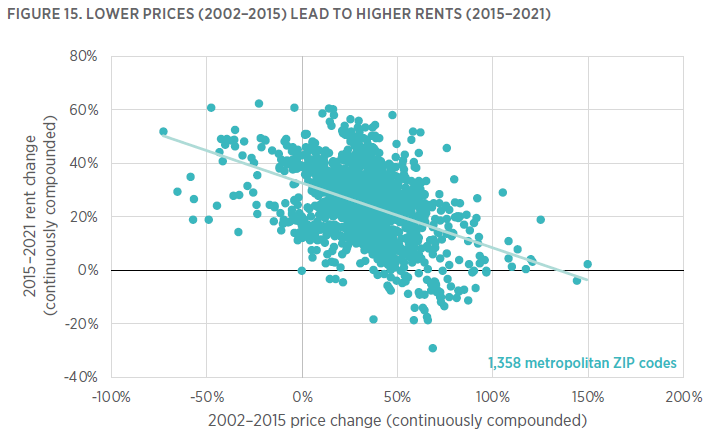

Where prices had gone down the most from 2002 to 2015, rents went up the most from 2015 to 2021. Sear Figure 15 into your brain. This should be a national embarrassment. Over this 6 year period, in the poorest neighborhoods where prices had been driven the lowest (devastating the net worth of young working class homeowners, by the way) rents increased by 40% more than rents in rich neighborhoods where home prices had appreciated the most. This is the transition from the center scenario of Figure 11 to the right hand scenario of Figure 11. This is a highly peculiar set of trends at a staggering scale.

This happened both within metropolitan areas and across metropolitan areas. Figure 16 compares the average per capita income of the 50 largest metro areas to rent changes from 2015 to 2021. Rents rose more in poor cities than in rich cities because poor cities stopped building adequate homes.

We made every city more like LA. It had been the case that it was harder to be a poor family in a rich (meaning, housing deprived) city. Now, by imposing a shock on housing construction across the country, we made it harder to be poor in poor cities too.

Eventually, rents increased enough to raise prices back to the level required to induce new construction. I think this is largely the reason why we have recently seen the rise of single-family build-to-rent markets. Those homes now have prices high enough to justify building them. Their relative rental values are much higher than they had been before. And, the CFPB and FHFA make sure that their residents can only be renters and not buyers. So, the homes have to be sold to someone else who will rent the homes to the residents.

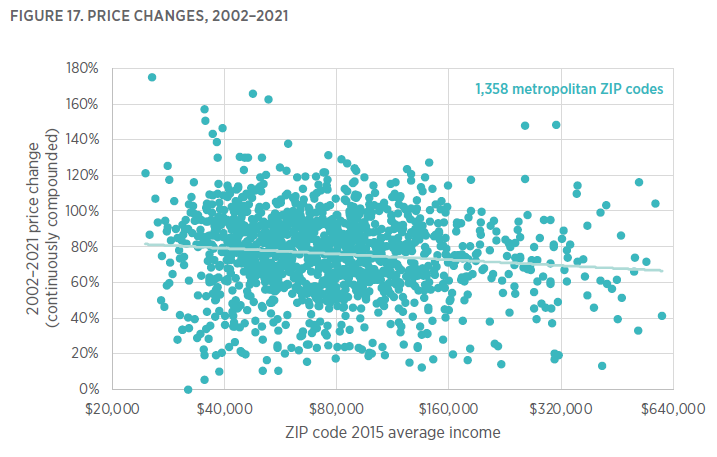

Figure 17 shows that, now, after the massive rent spike to get to the right scenario of Figure 11, prices over the entire period from 2002 to 2021 have risen at about the same average pace, regardless of local incomes.

Attempting to bring down housing costs by limiting home buyers had no effect, in the end, on prices. How could it? But, it had a devastating effect on rents, pushing them much higher for residents who have been regulated out of the buying market.

This has ended up having a dampening effect on regional population trends. Remember back to part 1. At any point in time, the difference in construction activity between metropolitan areas is largely due to different population growth rates. Average household size is about 2.5 residents, so each 10 new homes per 1,000 residents can accommodate about 2.5% population growth.

We have had a bit of a housing boom lately. Cyclical housing demand in 2019 was similar to what it had been in 2006. As I outlined in part 1, the country tends to experience cyclical housing trends universally, so at any given time, every city must build enough to meet cyclical demand, regardless of population growth. In these two years, cities had to build 2 units per thousand residents to meet cyclical demand, before accounting for population growth. So, in each of these two years, the typical city built 2 units per thousand residents plus one unit for approximately each 2.5 new residents.

The difference between these two years is that the growing cities grew much faster and built many more homes in 2006 than they did in 2019. They had both higher construction rates and higher population growth in 2006 than in 2019.

We have turned every city into a Closed Access city. Back in 2007, it was only LA where low tier housing had appreciated much more than high tier housing. Now, it’s everywhere. Now, every city is a Closed Access city.

New York, LA, San Francisco, and Boston still have the peculiar characteristic that they hemorrhage population when there is even a moderate rise in cyclical housing demand. In 2005, they moved to other cities, and a few of those cities became overwhelmed by the inflows. Today other cities are overwhelmed by the inflows at much lower rates of population growth and housing construction. But, more corrosively, now these constraints are creating the same picture in home price patterns that LA had in 2005. Prices are relatively higher in neighborhoods where incomes are lower. This suggests that the intra- and inter-metropolitan chain of displacement that comes from inadequate supply has become the norm everywhere. Now, in all cities, moderate demand is leading to higher rents rather than more construction.

And, we did it by cutting off mortgage access to the households that used to be able to buy homes. That will be the focus of part 3.

For anyone out there who still subscribes to the idea that overbuilding caused the Great Recession, then the trend towards all cities as closed access is a solution, not a problem---and these idiots seem to be the ones who set mortgage policy (I'm guessing you'll touch on this in your next post). This madness of induced scarcity has also had the effect of inverting the depreciation effect for older housing stock--junk houses command prices that exceed their replacement cost. Granted, wealthy people will make improvements to old houses and developers will do tear-downs for new build flips, but this is an arms race that is concentrated in desirable neighborhoods. The housing constraints in Metro Boston tend to raise the price of junk houses in marginal cities and towns off the ring highways.

The same thing is happening in Australia. Not enough supply, and they are cranking up rates...cutting off supply (and causing housing-cost inflation, btw).

OK, tin-foil hat time:

In the developed world, the way to expand or contract the money supply is executed through the commercial banking system. This is a premise, although why it is a premise appears rooted in sacred history, not intelligent design.

Commercial banks are loath to lend without collateral, and largely that means property.

You see what is going on here? If you want to goose the economy, it is done through the property sector, and cool off...

This set of circumstances is accepted...but who would actually design such a system (besides Rube Goldberg)?

Add on property zoning to the witches' brew...

So to the present day...in the US (and most of the developed world) we "fight inflation" by beating up on property lending (which helps tighten housing markets).

There is a better way, likely money-financed fiscal programs. Which also would free up taxpayers from ever-mounting layers of debt.

And a 10-year moratorium on property zoning...