The Housing Bust Was Not A Cyclical Event

Ezra Klein has been championing supply-side progressivism or a liberalism that builds. Recently, he wrote about two critiques of his approach - a critique from the right by Reihan Salam, the president of the conservative Manhattan Institute, and a critique from the left by David Dayen, the executive editor of the liberal American Prospect.

I think Klein is pushing the right ideas, and the discussion is interesting. Here, I want to touch on part of the back and forth between Klein and Dayen, because it relates to housing, and I think it is an example where what they agree on is as important as what they don’t agree on.

First David Dayen:

For example, a classic “supply-side progressive” argument goes that zoning rules make it illegal to build multifamily housing in much of the country, leading to sprawl and undersupply and spiking home prices. In addition, community input offers far too many veto points from loosely organized homeowners, who are incentivized to restrict building to preserve property values.

That is all absolutely true, and some areas seeing the most affliction—my home state of California in particular—are belatedly trying to do something about it, with a series of legislative actions to force upzoning and increase supply. But there can be no doubt as an empirical matter that the greatest source of undersupply in housing in the past 20 years came from not a zoning rule or community outcry, but the impact of the Great Recession. In 2007, the top 200 builders closed over 389,000 units; within two years, that was cut by more than half, and even in 2017, a decade later, only around 327,000 units were built.

Because we have limited public funding for housing in America, we are at the mercy of the free market. With no social-housing sector, whenever private developers pull back, affordability suffers. And when the housing bubble collapsed, for-profit homebuilders resisted risking capital on what was seen as a hazardous business.

A decade of consolidation ensued, with firms either closing or pairing with bigger rivals. “You had pipe farms, suburban developments with just the pipes sticking out of the ground,” said Dan Immergluck, a professor at Georgia State University and author of Red Hot City, about the Atlanta housing market. “That causes the labor to migrate.” Suppliers fled too. So when the pandemic hit, the system was so fragile that doors and windows and lumber became hard to come by, along with the workers to install them.

The reply from Ezra Klein:

When Dayen turns directly to topics like housing, his arguments go awry. He argues, for instance, that part of the housing crisis is insufficient construction in the aftermath of the Great Recession. True enough. But that doesn’t explain why it’s functionally impossible to build a six-story apartment building in the most undersupplied neighborhoods of San Francisco and Washington, D.C. Yes, housing manufacturers misjudged demand 10 years ago. But that is not why they cannot more rapidly increase supply now. Apartment buildings are not technically hard to build. They are politically hard to build.

There is an important core of agreement here. The first paragraph and a half from Dayen is the deal. Klein, Dayen, and I would all agree on that. End it there, tie it up in a bow, and “Let’s goooo!” build some housing. But, unfortunately, Dayen doesn’t stop there. The rest of his argument is misguided. Klein pushes back. But, he has that little nugget in the middle, “Yes, housing manufacturers misjudged demand 10 years ago.”

You can call me pedantic. You can say there is room for agreement and agreed upon progress without shoring up every little bit of confusion. But, Klein’s stipulation is wrong, and it opens up the door to all of Dayen’s mistakes. It gives away too much. The Klein’s of the world need to get this straight, because the Dayen’s of the world understand the entire problem. But, it’s buried under a pile of misjudgments. Those misjudgments demand a full throated dissent.

These mistaken sentiments create a sense of fear about letting private construction markets solve the supply problem. Letting those markets work is a prerequisite for every tactic anyone wants to apply to try to lower American housing costs, including publicly provided and subsidized housing.

Overly-cyclical housing markets are absolutely not our problem. That is the opposite of our problem. Our problem is that some cities have cut off the top of the housing cycle so that it looks like Figure 1. When demand for housing grows, those cities hit a cap in housing production, and so as demand rises, instead of building more homes, those cities shed people.

The Closed Access cities (New York, LA, Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego) have been bleeding domestic outmigration year in and year out since at least the 1990s because of a lack of adequate housing, and the more homes they build, the more people they lose, because of this problem.

The Impact of the Great Recession

Dayen is correct that the Great Recession is overwhelmingly responsible for the additional and more universal supply shortage that has arisen since then.

He is wrong, though, to attribute this to market forces, and Klein is wrong to stipulate to that error.

He attributes the drop in production to risk aversion and consolidation in the construction industry, noting that by 2017 construction by the top builders was still below 2007 levels.

I would like to consider two points on this claim.

(1) Where local supply constraints bind, the market recovered by 2013

Figure 2 compares housing permits in the Closed Access cities, permits in the US, and permits in the US outside of the Closed Access cities.

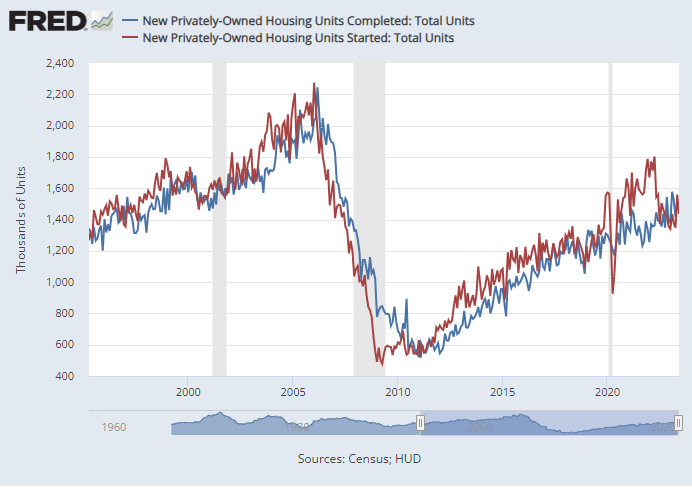

Before the Great Recession, the US built around 5 to 7 units annually, per 1,000 residents. As I have written about exhaustively, the boom in the 2000s was quite moderate. There was nothing unsustainable about the level of building. It was well below per capita construction rates that were common before the 1990s, and where building was elevated, population growth was high and/or vacancies were low.

The national rate of about 5 units per 1,000 residents in the mid-1990s is a good estimate of the baseline level of construction required to minimally maintain the housing stock for a population growing roughly 1% annually. Notice that the Closed Access cities never get close to that minimum. That is why millions of Americans have been displaced from those cities over the past three decades.

Before the Great Recession broke us, the rest of the country had to build an additional house per 1,000 residents each year in order to house the Closed Access refugee families. The destinations of those domestic migrants are not evenly distributed, so a few cities tend to take much of that flow. I call them the Contagion cities. And if there was anything unsustainable about the 2000s housing market, it was that so many families were flooding out of the Closed Access cities that the population spikes outpaced the ability of the cities that were taking them in to build.

The pressure from the lack of homes in the Closed Access cities, ironically, is what created the impression of unsustainable housing demand which led to the moral panic of 2008.

Figure 2 highlights two underappreciated facts.

Homebuilding had already contracted to well below the sustainable minimum before the recession began in 2008. Klein’s stipulation connecting the depth of the subsequent bust to pre-recession builder optimism is as bafflingly wrong as it is popular. Speculative overbuilding can’t explain the years-long slow recovery. As I wrote in “Build More Houses”:

Ben Bernanke wrote in his memoir: “Builders would start construction on only about 600,000 homes in 2011, compared to more than 2 million in 2005. To some extent, that drop represented the flip side of the pre-crisis boom. Too many houses had been built, and now the excess supply was being worked off.” The years 2009 and 2010 saw fewer new houses as a percentage of the existing stock of housing than any other 2-year period since at least 1965. In fact, the same can be said for the 3 years leading up to 2010, the 4 years leading up to 2010, and so on. For every period of any length of time since 1965, the period ending in 2010 is the period with the lowest number of permits and shipments as a percentage of the existing stock of homes.

This error is not just a matter of minor pedantry. It has already created a massive amount of economic dislocation and policy misjudgment at the highest levels.

The Closed Access cities topped out at 2 to 3 units per 1,000 residents annually before the Great Recession. They were already recovered back to that range by 2013. By 2013, we were back to the scenario where a housing cycle was hitting the cap in the Closed Access cities. The migration of families out of those cities started to rise again. But, this time, there were no houses for them elsewhere.

(2) The cyclical bust was public policy, not a market reaction

As I track, here, with the Credit Component on the Erdmann Housing Tracker, and as I discussed in “Reassessing the role of supply and demand on housing bubble prices”, there was a deep shift in credit standards after 2007 that reached well into prime lending and which was maintained by the federal mortgage institutions.

Figure 3 is from the paper. This tracks the average credit score on newly originated mortgages at Fannie Mae, and it tracks the median price of homes across the US, the average price of homes that had previously received Fannie Mae mortgages, and the average price of homes receiving new Fannie Mae mortgages. As I wrote in the paper:

Notice that from 2000 to 2007, while credit scores at Fannie Mae remained stable, the average price of homes with new mortgages was roughly tracking the average price of homes with existing mortgages. In other words, until 2008, Fannie Mae was making loans to the same types of borrowers in the same types of homes as before the housing boom, but then Fannie Mae retreated from the low-end market. From 2007 to 2009, the average current market price of existing Fannie Mae homes declined, along with homes across the country (estimated here with the Zillow median US home price). However, at the same time the average price of homes receiving new Fannie Mae mortgages shot up from around $250,000 to more than $300,000.

The federal government effectively cut off lending to millions of households who had been traditional prime borrowers in the decades before the 2000s credit boom.

In that paper, and here at the Tracker, I track the effect that shift had on prices. But, it also had a tremendous effect on construction. I touched on this in my most recent Mercatus paper. Construction collapsed the most in cities with lower incomes and rents have subsequently risen the most where incomes are lower. We created a class-based housing bust through mortgage suppression. (It turns out that one of the main effects of decades of generous mortgage lending programs had been to lower rents on working class housing.)

Figure 4 is a broad attempt at quantifying the class-based bust at the national level. Using data from the New York Fed on mortgage originations by credit score to estimate home buying activity, I have 3 categories of new housing: (1) multi-family units, (2) single-family units to buyers with credit scores less than 760, and (3) single-family units to buyers with credit scores more than 760.

As with the Closed Access vs. the US distinction, there isn’t one uniform market here. New homes built for high score families have fully recovered. Multi-unit construction has fully recovered. And single-family homes for low score families have not recovered at all. (Actually, a 760 credit score is not that low. It’s around the 70th percentile.)

However many millions of units you think underbuilding since the Great Recession adds up to, it’s all from a lack of single-family homes sold to families with credit scores below 760.

There are 3 caps acting here:

The single-family homes sold to buyers with credit scores over 760 are capped by a natural satiation of demand.

Multi-family construction is capped by regulatory obstructions.

Single-family homes to buyers with credit scores under 760 is capped by the FHFA and the CFPB.

The second two categories are related, because when the feds blocked access to mortgage funding for single-family homes, those families needed an outlet. I think the clearest way to think about post-Great Recession housing is that the same urban anti-apartment afflictions that have turned the Closed Access cities into refugee machines were lurking in cities across the country. But, many cities could cover over those trends by approving entry level single-family homes in the exurbs. The mistaken mortgage regulations applied after 2008 ripped off that band-aid. And, when working class families needed a new source of urban housing, there was nothing that could step up to the plate.

So, families with less than pristine credit have had to pile into the existing stock of homes. In total, American housing consumption has flat-lined. But it didn’t flatline for families with credit scores above 760. New housing for families with credit scores below 760 has been well below the minimum sustainable level. And, so rents have been rising everywhere, like never before. And when they rise, they rise on the families who can least afford it.

It wasn’t builder risk aversion and consolidation that caused this. The demand wasn’t there for single-family construction because the federal government cut off mortgage access. And, so, when all is said and done, even the undersupply that was the result of the impacts of the Great Recession leads us back to zoning that limited multi-family construction from filling the gap. There was demand for living in those homes, but the single-family builders couldn’t build them because the residents couldn’t buy them, and the multi-family builders are down at the city building getting lectured on neighborhood character. Perhaps the burdgeoning market of single-family homes built for rent can thread the needle to finally fill in some of the gap - by avoiding overzealous mortgage regulators at the federal level and overzealous apartment haters at the local level. Neither obstacle is reasonable. My fear is that rather than fixing those unreasonable obstacles, new obstacles will be invented, leaving tents as the final urban housing option - a market segment whose growth has unfortunately been leading all the others already.

The Fed

Dayen does implicate public policy in some pro-cyclical housing outcomes. The next line after the excerpt above is, “Just as housing starts were starting to bounce back in 2022, Federal Reserve interest rate hikes made it more expensive to build, and starts plummeted again.”

As with all his mistakes, this one is understandable. I have gone into some detail here at the Tracker about what exactly has been happening with housing starts. As Figure 6 highlights, starts had gotten ahead of the industry’s ability to complete them, because of the hysteresis Dayen touches on in the excerpt above. So, the Fed has really succeeded in recent policy decisions by pulling demand down far enough to pull starts back down to a sustainable level without slowing down completions.

It is good that Dayen can appreciate the potential for public policy to fuel pro-cyclical market outcomes, but he has applied it in the one context here where that isn’t accurate.

Again, this points to the power of the oversupply mythology that drove the country into crisis in 2008. In 2006, the Fed did maintain monetary policy tight enough to lower housing starts. At that time, Americans needed more homes and builders had the capacity to complete them. So, when starts precipitously declined in 2006 and after, so did completions. (Rent inflation, which had finally been moderating when housing construction in 2005 finally rose above the minimum sustainable rate, spiked back up in 2006.)

Pro-cyclical Fed policy did hurt Americans’ capacity for housing after 2005. But, of course Dayen and Klein, and the rest of punditry, are in general agreement against that suggestion. Everyone would agree that there was a cyclical shock. But they treat it as fate rather than an errant policy choice.

Also, again, on the things they agree on, it is hard to support the idea that builders were optimistic when housing starts were well below sustainable levels before the recession hit. In fact, one of the links in Dayen’s excerpt above goes to a retrospective article in a builder trade journal about a May 2007 article which had been extremely pessimistic. And, even by May 2007, builders had been dealing with high rates of buyer cancellations for a year.

This is a point I touch in in Building from the Ground Up. Builder cancellations spiked higher and earlier than mortgage defaults did and before home prices broadly collapsed. The builders had a very early read on the turning market, and acted on it.

This is especially noticeable if you look at single-family starts versus multi-family, as I do in Figure 7. Even cumulatively, the increase in starts from 2003 to 2005 had been reversed by the time the crisis hit in September 2008.

And, look at multi-family starts. (Keep in mind - these are starts, not completions. This is not a product of construction processes.) Multi-family starts remained strong right up to the September 2008 crisis. So, single-family starts had declined 65% from their peak and more than 50% from a cyclically neutral rate of housing production before multi-family starts even budged.

Maybe single-family builders were pessimistic but all the pro-cyclical optimism was in multi-family? Is that a story anyone has been trying to tell? Did we have an oversupply of housing in 2008 because of an extra 300,000 multi-family units?

Oh, and, by the way, multi-family starts were recovering by 2010 and were back to peak levels by 2012! Wouldn’t it be weird if the slow recovery was due to risk averse builders, but the one sector the builders piled back into was the sector with the most risk and the longest production time?

Of course, because our fundamental problem is a deep and broad regulatory opposition to multi-family housing, the recovery in multi-family in 2010 was economically insignificant. As things are, it would have to rise to double its current size to bend the arc of housing production toward a sustainable rate.

There are those who will throw their hands up and say that private developers just can’t meet that demand. Infill development is just naturally difficult. As shown in Figure 4, multi-unit construction has topped out at around 1.5 units per thousand residents for the past 30 years. Before that, 1.5 units was a recessionary bottom, and multi-unit production would rise to as much as 4 units per thousand residents during building booms. These units will be, and have always been, built where they are legal.

Could we get even remotely close to that level of multi-family production today before the myths of the Great Recession lead to a pluralistic call for monetary tightening and a construction slowdown?

In Figure 7, to highlight the effect of post-2008 mortgage suppression, I also put high tier and low tier Case-Shiller home price indexes for Atlanta on the chart. There are 3 stages here: (1) pre-recession cyclical collapse in single-family, (2) broader collapse, (3) post-recession recovery in apartments and high tier single-family, coupled with the underappreciated further collapse in low tier single-family.

Klein and Dayen, joining the broader consensus, have missed the early collapse in builder activity and sentiment at the front end, and have missed our intensive final groin punch to working class homeowners at the back end. A narrative putting the causal blame on builders starting too many single-family homes in 2005, because they didn’t foresee that there would be no working class buyers in 2010 is hopelessly confused. Until we get past this, these errors will creep into every debate about our housing problem. Buried below these errors is a consensus about what is really wrong! We already agree on the solutions! The easy part is done!

Finally, just one final note, Dayen’s explanation for the decline in sales - risk aversion and consolidation - doesn’t really even hold up on its own terms. Again, it’s understandable. I think this is common on many issues related to the housing boom and bust. The conventional wisdom is built on a foundation of myths, and so it’s awkward because reasonable explanations are unimaginable from that framework, only unreasonable explanations remain as options.

How exactly does he think “when the housing bubble collapsed, for-profit homebuilders resisted risking capital on what was seen as a hazardous business” played out? This is the sort of thing that makes sense in the abstract, especially when there is a narrative that this helps explain. We all have to make these sorts of inferences on complex issues.

As I pointed out above, his inference doesn’t seem to have applied to multi-unit construction. Single-family builders either build spec homes or they build homes for funded clients who put down a deposit. I don’t think builders were turning away custom home buyers. I don’t think it is plausible that in 2015, there were hundreds of thousands of families who wanted to buy a custom new home, who traveled from builder to builder begging one to take their money, but being turned away by all of them. If anything, it was the banks who turned them away, and they never showed up at the builders’ offices.

Builders always build spec homes in proportion to demand. People come in and buy a home that is either finished or under construction, and the builders start a new one to replace it. Again, I don’t think builders were refusing to sell completed inventory because they were risk averse. They certainly weren’t leaving “pipe farms” unfinished because they were risk averse. The pipe farms were the result of their buyer’s market being pulled out from under them. The market wasn’t being pro-cyclical. A one-time monster negative shock was imposed on them, and they were victims of it. They had no customers. That shock led to the “pipe farms” and industry consolidation, not the other way around.

Summary

There are three distinct areas here. And the issue on each isn’t that Klein and Dayen disagree. They agree on all three.

(1) The truth: They agree that zoning regulations are a problem. This is great. Let’s fix it together!

(2) Errors of commission: There isn’t a dangerously pro-cyclical private construction industry. There is nothing to fear. And, the true causes of our decade of housing deprivation require eschewing the false ones.

(3) Errors of omission: I suspect that neither Klein nor Dayen have paid much mind to the post-recession mortgage suppression that blocked new single-family construction and that destroyed working class wealth in places like Atlanta. This has been lost in the fog of truths and untruths. We could probably return to a norm of 30-something and 40-something families with 720 credit scores regularly using mortgage credit to buy new homes. Nobody seems to have noticed when we lost that. Maybe nobody will notice when we get it back. Can some hacker secretly tweak the underwriting code at Fannie and Freddie while everyone continues to debate other stuff?

Klein’s acquiescence that “Yes, housing manufacturers misjudged demand 10 years ago.” may seem like an innocent enough stipulation in order to move on to helpful compromises. But it is wrong. It has been the cause of incalculable economic distress already. It is handmaiden to a whole host of unhelpful myths about the dangers and potential lurking in housing markets. And, it supports a foundation for a number of myths which are routinely used to oppose the clear solutions which Klein rightly favors, and which detractors like Dayen already agree on.

The true narrative of the Great Recession housing crisis needs to be repeated at any opportunity. So, at the very least, the Klein/Dayen discussion gave you that opportunity again.

Also, Klein and Dayen, among others, seem to have moved on from the myth of over-produced housing from the early 2000's. That fiction has been harder to sustain in recent years because shortages, and subsequent prices increases, now seem to afflict every major metro area to some degree or another. I think the media has been doing a decent job of describing the unfolding situation with commercial office space, both as it relates to "price adjustments" and the architectural challenge of converting many of these buildings to residential uses. The next decade will be interesting for some cities, and if history is a guide, this will have positive impacts---if we can change zoning and historical commissions.