The Housing Shortage by Metro Area, Part 3

And, a note on new home sales

In the previous posts, I highlighted the scale of the housing supply challenge. Here is one more graphic with, maybe, a more hopeful framing.

Surely, each metropolitan area is capable of building homes at a rate equal to the rate it has in the recent past. And, even if one labors under the mythology that there were too many homes in 2005, surely we generally agree there aren’t too many now, and so our capacity to build can be safely tested.

So, in the Figure here, I show the number of homes short for each metro area, the shortage as a percentage of its total stock, the recent rate of home building, the rate of homebuilding in its peak building year from the last 30 years, the difference between the peak year and the recent average, and the number of years it would take to reduce excess rents if the city built at that rate again.

This actually helps highlight an important point, I think. In the original post, the right hand column estimated how many years it would take to erase the shortage at double the current building rate.

Most cities in the recent past actually have built at more than double the current rate. So, the previous figure actually overstated the problem in terms of their known capacity to build.

This really bifurcates cities between those whose problem is entirely local land use constraints (LA, Boston, New York City, etc.) and those that have been mostly harmed by the mortgage crackdown.

The peak minus average housing permits figure is probably a pretty good proxy for which markets will have the strongest single-family build-to-rent market. That market is basically filling in the gap of housing missing as a result of the mortgage crackdown.

So, not only do the cities at the top of this figure have the capacity to fix their housing markets, their markets are likely to start healing themselves on their own, until municipalities, states, or federal government ban build-to-rent. The cities at the bottom of the table are going to need to make extensive local changes to even begin to address the problem.

Don’t get me wrong. Every American city needs to rediscover city building. But, that’s a separate issue. The issue we have today, that has increased the national supply shortage from 1% to 10% in 2 decades, is a different problem. Solving that problem will reverse deeply regressive economic trends, which have a lack of housing at their base. It will bring the American working class back into a context of shared progress. And, as much as I have come to appreciate the importance of better city-building, the more recent economic problem related to the national housing shortage is much more acute and important.

October New Home Sales

A note on October new home sales relates to this point. This month sales dropped sharply, but in a way that suggests anomaly. Looking at regional data, it appears that it was probably generally due to hurricanes in the south. New home sales were up from last month if you take out the south region. And, that is also why the average new home price went up. Most of the price increase is due to the anomaly with the south, because new homes in the south sell for less than the west and northeast.

So, it was sort of a noise event, sort of a weather event, and sort of a supply constraint issue. But, however we describe it, it is very likely temporary.

Taking a longer view of regional new home sales, there are some interesting patterns. The South is generally populated with places that can grow. The West is a mixture. The Northeast is basically locked down against housing in the entire region (which is why the majority of outmigration from New York City and Boston is to Florida rather than New England or upstate New York).

The Midwest can build housing. Sales there boomed before 2008 as they did in the south and the west. But sales have recovered in the South and the West while they remain at 60+ year lows in the Midwest.

Why are they at 60+ year lows in the Midwest? The death of manufacturing? The China Shock?

And here, all the myths of the 2008 crisis and their consequences get their tentacles all tangled up into everything. The drop in new home sales that started in 2006 happened everywhere at once. That wasn’t because of the death of manufacturing. It was a universally approved policy target.

Manufacturing employment started to slowly drop in 2006 and then fell off a cliff in 2008 and 2009, as did construction employment. If that was a choice that should have been avoided rather than an inevitable correction that couldn’t be avoided, what would the “China Shock” and Midwestern employment have looked like after 2007 if we had decided it wasn’t actually a great idea to guide new home sales across the country down by 80%?

And, why didn’t home sales recover in the Midwest after 2008? The China Shock? Lost manufacturing?

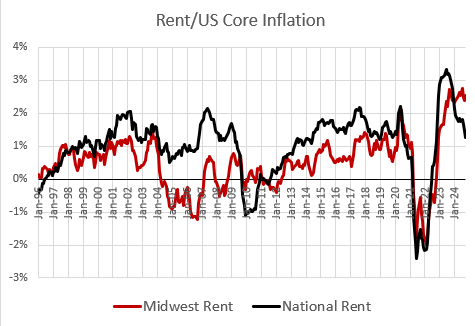

We might presume that there is no demand for housing in the Midwest for those reasons. But, that isn’t reflected in rents. In the decade through 2008, Midwest real rent inflation accumulated to only about 3%. Nationwide it added up to 14%. Today, 10 years of rent inflation have added up to 11% in the Midwest versus 15% nationally.

The Midwest used to have affordable housing, but now housing inflation is starting to track with the rest of the country. And yet the Midwest is hardly building any new homes.

We had a (mistaken) moral panic about too many homes built in Arizona and Florida, so we forced banks to stop making mortgages in Peoria. The vast group of laymen across the country who read my work and immediately react with “Oh! This dolt wants to go back to NINJA loans again! That worked out great!” don’t think that’s what they are supporting. But it is.

So, Chicago and Cincinnati do very well in Figure 1 here compared to my earlier table. If they simply could have a moderate building boom like they did in the 2000s, their housing issues could be solved relatively quickly. I didn’t include St. Louis and Detroit in the table, but they are similar to Chicago and Cincinnati in every respect.

The moral panic was about overpriced housing, but we waged a war on cheap housing. The Midwest was cheap, so it has been the odd front line for the war nobody noticed we are engaged in. The build-to-rent industry will be finding a foothold in the Midwest, to finally ameliorate the problem, until they ban it.

Add this to all the faux-inevitabilities. All the tragedies and crises that started piling up in 2008, to which the universal reaction was that we had it coming to us. We’ve throttled the Midwest housing economy for 20 years, and probably the broader Midwest economy too, and as we tightened our grip on it, we bemoaned how hard international trade has been on the region. “Such a shame. What-r-ya-gonna-do? And now, immigrants are driving up the rents. When are they going to catch a break?”

Is there an alternative explanation for this, other than the mortgage crackdown? The Midwest has, according to popular description, been left behind in the post-industrial transition. New housing construction has been flatlined since 2008. No demand for housing? Yet not a single month from 2013 to 2020 registered rent inflation that wasn’t excessive.

ZIRP did that? The Midwest, it turns out, has been a superstar city all along, with geographic barriers to exurban expansion? Construction capacity was tapped out in 2016?

It’s mortgages. To a first approximation, it’s all mortgages. And when build-to-rent comes along to put the last thumb in our housing dike, it will be met with fear and anger.

The first figure is very eye-opening. I hope that it goes viral.

In my jihad against lax over-lending on commercial property....

Office CMBS Delinquency Rate Spikes to 10.4%, Just Below Worst of Financial Crisis Meltdown. Fastest 2-Year Spike Ever

by Wolf Richter • Nov 30, 2024 • 13 Comments

Office-to-residential conversions are growing, but are minuscule because not many towers are suitable for conversion.

---30---

In fact, it is ugly.

Unlike housing, which is always in demand except in most-dying of Rust Belt cities, the office towers...really seem derelict. You can re-purpose housing into better housing, but not office towers, which take about $500 sf to re-do as housing.

Perhaps if building codes were radically altered to allow "substandard" housing to exist in old office towers there could be hope. Exposed conduit piping and plumbing, for example.

One developer suggests large "outdoor" patios on each unit might help. Self-storage onsite.

Maybe.

But a round of moralizing against against sloppy lending practices is in order, for sure.