The other day, I posted an estimate of the scale of the housing shortage, by metropolitan area. I have removed the paywall on that post now.

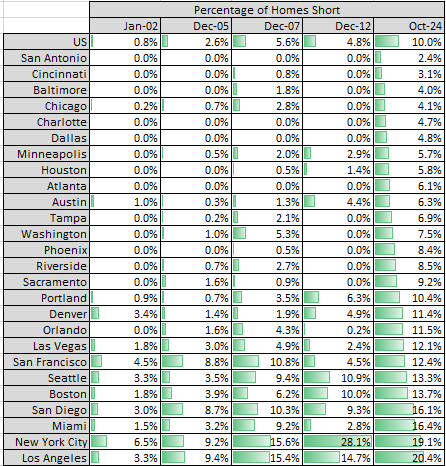

This is a quick update to show what scale of shortage the tracker would have estimated in 2002, 2005, 2007, and 2012.

Along the way, I realized I had a simpler way of calibrating the shortage of each metro area. The national estimate of the shortage is the same (about 10% of the housing stock), but for the 2024 numbers, with the new method, the shortage for each metro area is typically a couple percentage points lower.

As I wrote before, I’m working with a broad brush here for now. As I am able to revisit it, the numbers will change on the margin as I work out better ways to estimate the numbers.

Anyway, the reason I decided to add these additional points in time was to show that the model is not just calibrated to show large shortages.

The current national shortage of 10% of the housing stock is based on separate analyses that I have done with national data such as household size, housing permits, real and nominal spending on housing, etc. But using that as the benchmark, every other number here is strictly taking a quantitative measure of home prices. If low tier prices aren’t elevated, then the tracker doesn’t indicate a shortage. If they are elevated, then it does.

The new table is below.

The table in the previous post showed the number of homes short, that number as a percentage of the housing stock, the 5 year average number of housing permits for each metro area, and the number of years of production at that rate it would take to make up the shortfall.

Here, to keep it simple, I am just showing the shortage at each point in time as a percentage. And, they are ordered according to the current percentage scale of the shortage.

In 2002, the shortage was very regional. Regional domestic migration patterns reflected this. Most of the cities registering a shortage were posting a significant quantity of domestic outmigration by families that routinely list housing costs as their motivation. In 2002, the tracker would not have identified most cities as being in a shortage condition.

Until 2005, construction was increasing across the country to accommodate all those housing refugees. Between 2002 and 2005, the regional shortage got worse, but most cities were still amply supplied. But by 2006 and 2007, because of wrong-headed federal macro-economic policies, housing production went into freefall. The shortage condition did spread a little bit at that time. Rent inflation isn’t an input in the model, but rising rents at the time corroborate that conclusion.

Sentiment is changing a little bit. It’s a little hard for me to address this issue to a general audience because long-time readers will understand my point that during the boom before 2008, homes were undersupplied. But it might sound ridiculous to new readers. The long and short of it is that clearly the closed access cities are and have been undersupplied. Every year hundreds of thousands of Americans have to move away from those cities. That was true before 2008, and in the years before 2008 that housing refugee flow had been increasing.

It is true that rising demand for housing was a key reason for the hot market in 2005. In cities with a relatively fixed housing stock, rising demand for housing, per capita, necessarily requires outmigration. Our supply conditions are so constrained that housing demand would have to be increasingly suppressed each year in order to prevent our demand for housing to increase along with rising real incomes. The housing demand that leads to spikes of internal migration is very low.

After a decade of working on this, I feel like this should be easy to understand. In hindsight, given those conditions, “We’re building too many houses in the destinations those economic/housing refugees are moving to.” was a ridiculous and sadistic position to take. It was what we did. And the right three columns of this table are the result.

I understand that it’s a hard thing to come to terms with, and it divides people into those who see it as a revelation and those who will not see it. I’m not going to spend paragraphs litigating the point here.

When the production of housing across the rest of the country collapsed, the migration out of the cities with large shortages also slowed down. I think that is one reason the shortage measure worsened in 2007 in the regions where it had already been bad.

By 2012, the shortage had eased, but this was mostly due to the contraction of demand because of foreclosures, declining incomes, declining immigration, etc.

Remember what the economy was like from 2007 to 2012? That’s the demand-side way to fix the housing shortage.

Then, over the following decade, mortgage suppression kept construction at depression levels, and local housing conditions worsened almost everywhere.

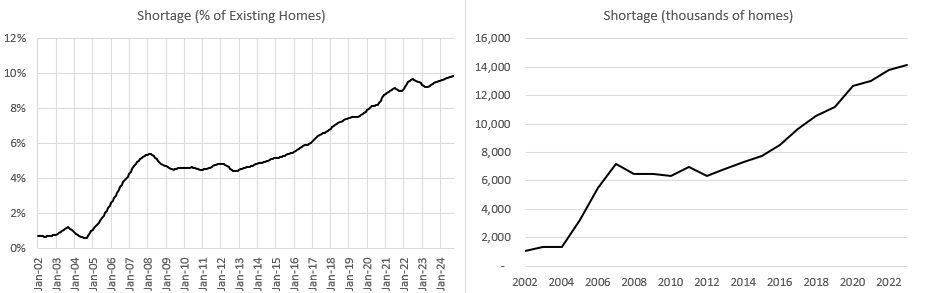

Here are some additional charts:

Figure 2: Monthly estimate of the national shortage from 2002 to 2024, as a percentage of the housing stock (left panel) and thousands of units (right panel).

Figure 3: Annual Housing Production and the total number of units required to avoid the shortage, from 1968 to 2023. Units per 1,000 residents (left panel). Thousands of units (right panel).

The scale of construction required to avoid the shortage would have been quite manageable, year to year. Of course, it’s hard to construct a counterfactual, because the collapse after 2008 was a reaction to what had happened before. If we had governed for stability in 2008, the building boom might have still ended with some sort of recession, as the booms of the 1970s had. But, it probably wouldn’t have been as deep. Construction would have been higher from 2009 to 2012 because we wouldn’t have seen such a drop in incomes and wealth.

Also, in the estimates in Figure 3 of the required number of homes to prevent a shortage, I added guardrails on maximum growth rates and maximum units per capita, to remain within the historical range. That would not have completely met demand in 2005 and 2006. That would have led to temporary price deviations and temporary changes in vacancies. Of course, that would all happen without the mortgage crackdown, so it’s hard to assess exactly how it would have compared to the price and vacancy trends we experienced.

Figure 4: Estimated Shortage over time for Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Houston

Notice that the surplus in Phoenix is not from overbuilding in 2005. It’s from the collapse of migration after 2005. By late 2008, when Phoenix registers a surplus, housing production had been in collapse for years.

Compare that to Houston. Let me yell this so that those in the back can hear it. “Cities never overbuild to a surplus. If you think they do, you’re hunting heffalumps and woozles, and the surplus in Phoenix in 2011 is the footprints you just happened upon.”

As I have written before, a city like Phoenix that was growing by 2% or 3% per year could not physically build more than a few months of vacant inventory. Surpluses are always and everywhere caused by crashing demand.

So, liquidationism and “letting the downturn play out” to discipline the market is the disease. If that is what you think proper macroeconomic management of housing markets requires, you are Typhoid Mary.

Also, note how Los Angeles has basically peaked at 20%. That’s not because they have been building enough housing. It’s because once the shortage becomes that acute, it induces permanent regional displacement. “Supply” is permanently created by permanently moving a family away rather than building new units.

Also, just a reminder, this is still a work in progress, and if I get a chance to reproduce this data with controls for things like property taxes and density, there will be some moderate shifts in the estimates.

Thanks for drawing my attention to Salim Furth's comments on Twitter about the additional burdens associated with Environmental Justice that Massachusetts places on large development projects. He summed up my state's housing policy as "one step forward, two steps back." The anti-development mindset has been entrenched in many parts of New England for decades. For many people, it's a point of pride when a project is killed or scaled back.