In the first 2 posts of this series, I have made the argument that demand for housing becomes inelastic under conditions of locational scarcity, and this is the source of most of the increased spending on and value of housing. What this means, in the aggregate, is that the more we spend on residential investment (in terms of capital inputs), the less we spend on housing (in terms of annual rent and imputed rental value).

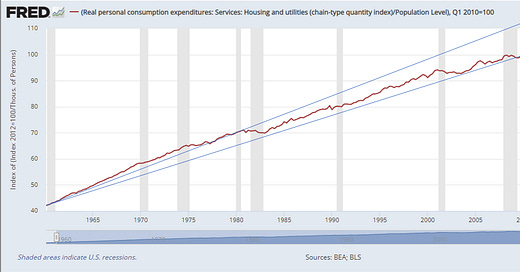

In previous posts, I have argued that real rental expenditures have been negatively correlated with rent inflation over time. Since the 1970s, Americans have had to pay more and more for less housing. (Before 2008, it was just less housing relative to our growing real incomes, but after 2008, it actually became bad enough that real per capita housing flatlined, in absolute terms.)

We end up with a pattern where for each 1% drop in real residential investment, residential inflation rises by more than 1%, so that, systematically, housing takes more of our incomes as we consume less of it.

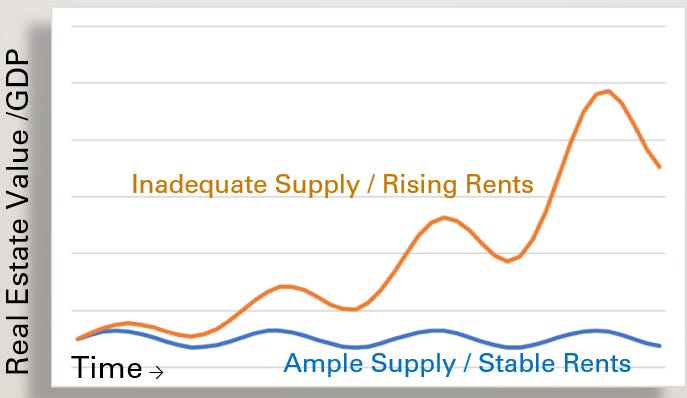

This seems counterintuitive, but is sort of obvious when you compare relative real estate values in a city like Los Angeles to a city like Houston. In the land of McMansions, aggregate real estate value relative to local aggregate income is similar to what it was 20 or 40 years ago. In Los Angeles, where homelessness is rampant, families pile into little old houses, and thousands of people move away every year because they can’t find adequate housing, aggregate real estate is multiples more than it was 20 or 40 years ago, compared to local incomes.

This pattern is conceptually counterintuitive, but it isn’t hard to observe.

Comparing net residential investment to changes in real housing expenditures highlights a parallel pattern. The BEA estimates the flow of new capital into the housing stock, and the flow of services that come from the housing stock, and in real terms, those flows run parallel to each other over the last 60 years.

When we invest less into housing, the value of the service housing provides declines, and this leads to rent inflation that increases the total nominal expense of housing for tenants and value of housing for owners.

The price/rent multiple is higher for inflated value than it is for real value. Real housing depreciates and requires maintenance. Inflated rental value is just unearned economic rents, so it natural fetches a higher price. Price/rent ratios are higher in Los Angeles than they are in Houston.

So, the total value of US residential real estate is a multiple of its rental value. That multiple has risen over time as rents have become inflated. And, then, there is some cyclical variation around that baseline. As my “world’s most niche meme” highlights, it is common for the US housing market to be viewed as increasingly cyclical, but it is really just muted housing cycles that are fluctuating around a rising trendline as rent inflation and housing costs rise over time.

In this post, I decided to try another method for estimating the real vs. inflated value of American real estate.

In any given year, the housing stock increases in value because of residential investment, declines in value because of depreciation (which the BEA calls consumption of capital), and increases in value because of general inflation.

By measuring that cumulative change over time, maybe we can estimate how much of the value of the American housing stock is due to the real cost of new construction and how much is the inflated value of old homes due to inadequate new supply and upward filtering.

To estimate total residential real estate value, I used the Federal Reserve’s quarterly estimate of owner-occupied housing, divided by the annual rental value of owner-occupied housing, multiplied by the annual rental value of all housing. Assuming a stable relative price/rent ratio in owned vs. rented homes, this provides an estimate for the value of all residential housing.

Figure 5 compares the measured annual change in the total aggregate value of residential real estate to the real increase in the housing stock from residential investment (plus general inflation). There are 2 clear periods here. Before the 1980s, both measures increased at a similar pace. In other words, the aggregate value of real estate increased because we built homes. After the 1970s, aggregate valuations became increasingly volatile. The rising value of real estate since the 1970s has mostly been due to rising values on the homes that were already built!

Adding these differences up, cumulatively, is a bit dicey, because any bias in the way I am mixing together these measures will also accumulate. But, from 1947 to the mid-1970s, the measures track quite closely together. This is what should happen in a functional marketplace that doesn’t obstruct supply. And, the estimates of annual personal consumption expenditures on housing, which are divided between real and inflationary above, in Figure 2, provide a decent benchmark for double-checking. In both Figure 2 (the estimate of the annual real value of the service of shelter) and Figure 6 (the estimate of the real value of the stock of homes), the real value of housing has declined by roughly 20% compared to broad measures of real income and expenditures.

There are a couple of sizable anomalies here. The bump in the mid-1980s is plausibly related to a major tax overhaul that increased the value of the mortgage interest deduction. And, of course, after 2008, total real estate values were diminished by about 20% (or about 40% of GDP) through mortgage regulation. Without that, the effect of looser lending standards would be that residential real estate would be inflated by 140% of GDP rather than 100% (the red line in Figure 6), before accounting for the increase in residential investment and the supply of new homes that would come of it.

Eventually, if I can pull it off, I will come back around and use estimates like this to get back to the question of the scale of scarcity vs. amenities in urban residential real estate values.

The point I have been trying to make is that amenities related to density and agglomeration economies are real, but they are just not remotely at the scale that scarcity has caused prices to rise. There are some central urban locations that will gain value if cities like Los Angeles start allowing an appropriate amount of building. But, most of the city is vastly overpriced because of scarcity, and will simply still have the same homes on each lot that are there now, but at a fraction of their current market value.

As a first approximation, you could say that the inflated real estate value in Figure 6 (the red line) contains a combination of both scarcity value and urban amenities value.

This is a bit complicated, because the value of urban density doesn’t necessarily flow to land value. Dense building costs more. In a market without transactional frictions, it could be that land value in the dense, amenity rich core doesn’t rise that much where building is ample. More units might be constructed until the added cost of new units in the dense core matched the added value of the location, and land values would be little changed.

Chicago is still a reasonable example of this sort of market. It is a city with less scarcity inflation combined with significant density-related urban amenities. Price/income in richer neighborhoods (in 2019, before Covid) was around 3 and in poorer neighborhoods it was around 4. That’s pretty close to a pattern with minimal scarcity value. Homes in dense neighborhoods fetched about a 30% premium, and residents of dense neighborhoods, on average, had about 30% lower incomes than in the exurbs. So, price/income ratios were about 60% higher in dense neighborhoods. Some of that might due to higher construction costs. Some may go to land value. And, also, residents in the dense core tend to live in smaller units. The interaction of all of these margins makes it difficult to say that “x” amount of density will add “x” amount of land value, but it may be possible to say that it would add “x” amount of real estate value, which is the result of all of those margins.

Actually, even the value of density is more complicated than that, because it’s really mostly a matter of a pre-existing “x” amount of density already being there in Chicago or New York City, and that density became more valuable over the last couple of decades.

This is part of the reason I say that scarcity value is of a much larger scale than density value. As huge as our housing shortage is, the amount of housing that would lower rents from relieving scarcity is much less than the amount of housing it would take to bring Naperville up to the density of Evanston.

In any case, I am hoping to quantify the answers to these questions as much as I can. Chicago is probably a case where there isn’t that much scarcity value to lose and there is inherent density value to mine. New York City has a lot of both, so it will be interesting to try to quantify.

After some initial poking around, I would admit that I may have underestimated the density value in New York real estate. A meaningful portion of the increase in real estate costs for residents with low incomes in New York City may have come from the increased value of the location rather than from the upward filtering of housing due to supply constraints. I still think it is reasonable to expect broad upzoning to reduce total real estate value (and thus, especially, total land value). But, it might be closer than I imagined.

Yet, the math just seems clear to me. Chicago price/income levels are between 3 and 7 in the densest ZIP codes and less than 3 in the least dense ZIP codes. But they are frequently in the double digits for both LA and NYC. And, looking at Figure 5, total value across the country is plausibly double the real value, and yet even in these cities that are the best examples of amenity rich dense cores, density appears to be associated with 20-30% premiums on unit value.

Teasing out the scarcity effect from the amenity effect is not going to be easy, though. And, one reason is that density doesn’t uniformly attract high income residents. The amenities of density may be at least as valuable to poor residents as to rich ones, and this creates some messy causation mysteries when the incomes and/or home prices of a dense ZIP code change.

That’s all a preface to future posts. Figure 6 was the main point of this post. It may be closer to a back of the envelope scribble than it is to a peer reviewed report, but I think it’s a pretty reasonable first impression for thinking about how expensive housing should be and how much potential there is for new residential investment.

PS. In hindsight, I realize that Figure 5 would have been more clear if I substracted the general level of inflation from all of the measures. This adjustment doesn’t affect Figure 6.

Here is Figure 5 with REAL changes in residential real estate values vs net real residential investment.

I admire Kevin E.'s intellect and patience in addressing these issues.

BTW, young Canadians are talking about leaving Canada. At the core, housing, with a dose of heavy taxes tossed in.

The orthodox macroeconomists insist living standards are higher in North America than 50-60 years ago. To be sure, wonderful technologies are available, from internet smartphones to non-stick pans, to much better flashlights and word-processors. I assume for most types of healthcare, today is better.

But who can raise a family anywhere on the West Coast? After taxes? Let's move the NYC and start a family?

It sure seems to me living standards are lower than 50-60 years ago.

Globalization and labor-busting immigration meet NIMBY?

Have you considered the impact of subsidized mortgage rates in this analysis? Another thing that happened post 1970's is the GSEs. I suggest complementary goods analysis between owner-occupied housing and mortgaged borrowing. (Most people buying houses have to borrow money to do so. Everyone with equity in a house has access to borrowing at a lower cost than typical non-homeowners.) That's how the mortgage interest deduction should come into the model. The GSEs play in multifamily, too, so it would be reasonable to add that, but it's probably a smaller effect there. Maybe a bigger effect in multifamily would be the tax preferences that played a big role, especially, in the early 80's.

I got a laugh from a conversation (probably around 2006) with a well-known chief economist in the housing business, who claimed that home prices would drop by 10% if the mortgage interest deduction was eliminated. In response I said, "so, you're saying that home prices are 10% higher than they should be, as a result of the mortgage interest deduction?" He didn't offer an answer.