The Secular Looks Cyclical

I saw this chart from a couple different sources on Twitter, and I thought it made for a great Rorschach test on the housing market.

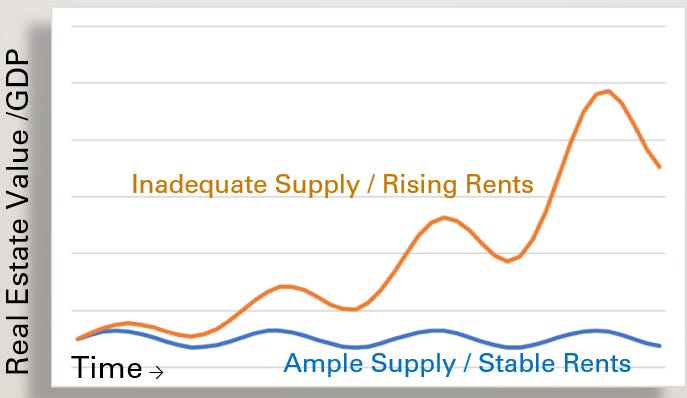

It is the international example of my “world’s most niche meme”. The first chart is, objectively, a chart dominated by cross-sectional variance. Japan and Germany are effectively versions of the blue line below. The other foreign countries are versions of the orange line, of various degrees.

If supply and demand curves have even a tenuous toe in the real world, then cross-sectional variance like this must be driven by supply constraints. It doesn’t matter what differences there are in demand. The only viable reason for such cross-sectional variance is variance in local land values and regulatory costs, which are driven by a lack of local supply to meet local demand.

One can argue that Japan has lower population growth than, say, New Zealand. But, practically every country has a lower growth rate than it did in the past when home prices were more moderate. And, in any case, the reason low population growth might be a reason that prices are more moderate in Japan is because it makes any supply problems less binding.

Price is necessarily the result of a dual causality. Even if supply is inelastic, prices only increase when there is demand. Interest rates are 3%? They could be 4%. 30 year amortization loans are available? They could be limited to 20 years. Default rates are 2%? They could be 1%. At all points along the orange line in the second, hypothetical chart, valuations could be decreased with some demand suppression of some sort.

So, if supply isn’t accepted axiomatically as the reason behind the variance in the first chart, then there is no falsifiable way to identify it separately from demand. The conclusion is either self-evident or inconclusive. This is why choosing a particular way of understanding the issue can be profitable! There is not a lot of direct evidence that can dissuade your counterparties.

And, I think the vast majority of people who look at that first graph simply see it as a house of cards. They see it that way because the shared cyclical movements are easy to infer, and so it is a real-world version of the “world’s most niche meme”. The various countries appear to have shared directional behavior, cyclically. And the only direction that seems to be a reversion to normal is down.

What does down mean, though? Does that mean the variance would disappear as each country returned to a “normal” price? Why? Why would there have been so much variance to begin with? I think most observers implicitly expect variance to decline as prices return to “normal”. I don’t think they expect prices in New Zealand to stop at 100% above the 2000 level while Japan shrinks to 50% below it.

Japan is the blue line. It is “normal”. So, observers who see the first chart as a chart of excess demand expect the variance to decline as markets (surely, inevitably) return to “normal”.

This is fascinating to me, because I can understand how the average person reacts to their personal experience in real time, when living through a period of supply constraints. It really does feel like a series of increasingly extreme inflated cycles. It’s a situation where the analytical brain has to convince the experiential brain that it has been fooled.

We have been playing repeated rounds of musical chairs and with each new round, we naturally look to the player that took the last chair and feel, sincerely, the truth that they were the problem: subprime lenders, speculators, home buyers with low interest mortgages, bottom feeding investors, private equity landlords. Go to any public meeting about local land use policy, and someone will give an impassioned plea about how they need to stop private equity from coming in and buying up all the homes in their neighborhood (which happens to be frozen in place in its 50 year old structural form by arbitrary local rules).

But, what is fascinating is that a chart isn’t experiential. It’s fundamentally analytical by construction. And, on a chart like this, clearly the overwhelmingly important detail is the variance: The difference between Japan and New Zealand. The variance in valuations is so extreme that surely one would be hard pressed to explain it with different local inflation rates, interest rates of a fraction of a percent, or different mortgage products.

And, for me, the chart is a good example of some of the basic points of analysis that drive my conclusions (some of them, counterintuitive). First, that the main source of rising price/rent ratios is rising rents. Right off the bat, it seems obvious that rising price/rent ratios represent a divergence from fundamentals - prices rising, in spite of rent levels. But most of the change in price/rent ratios is driven by changes in rents, which have more than a 1:1 effect on prices. Rising price/rent ratios are highly correlated with a market that is becoming more driven by fundamentals. The evidence from the US is highly suggestive that the variance in the chart isn’t from sensitivity to some imminently reversing cycle (“beta”, as financial wonks would call it). If the same patterns hold internationally, then home prices within New Zealand have become much more sensitive to relative rents than they have in Germany.

The intuition to see rising price/rent ratios as a sign of excess demand which will mean revert, is so deceptively seemingly self-evident, that I think it is an anomaly that is unlikely to be understood any time soon. (It would be nice if monetary and regulatory policymakers gave it a look, however.)

Second, as a lack of supply drives prices higher, cyclical volatility increases proportionately, just like in my hypothetical chart. New Zealand is more cyclically volatile than the UK is more cyclically volatile than Japan. The scale of the secular constraint increases the experienced sensitivity to cyclical fluctuations. But the differences between most of these countries is the slope of the trends, which has little to do with interest rates, cyclical fluctuations, etc. The low points in 2012 or 2020 were the reversal of beta. That’s all you’re going to get until supply is loosened, if you’re waiting for “normal”.

Third, the US generally has the average supply condition of a marginally broken market (being a combination of Closed Access cities with terrible housing policies and a number of vibrant regional centers with either better policies or room to grow out). But the US created a one-time price shock in 2008 by instituting heavy-handed mortgage regulations. Those regulations were imposed on a platform that was explicitly under the spell of the “cyclical mistaken as secular”, with the intention of keeping prices “normal” by preventing buyers from paying the prices that our supply-constrained markets called for. They succeeded, such as they were, and so we look a bit like Germany even though we have the supply conditions of the UK, Australia, etc.

You can see that most of the deviation that directed the “US” line away from the expensive countries and toward Germany happened from 2007 to 2010 when the average credit score on approved US mortgages jumped from 720 to 760. Basically, plug the credit component adjustment from the Erdmann Housing Tracker in to that graph, and the US price/rent chart looks like the UK. (I’m a bit embarrassed. Here I am, appealing to differences in demand - through credit regulations - to explain the difference between the US and the UK. I’m right back at the dual causality of supply and demand. Who could deny that these prices could surely all be pushed down to Japan levels with more financial suppression? Clearly, one could argue that levels of financial excess explain this variance. Even I am! Why limit the explanation to the US from 2008 to 2010? Am I stubbornly grasping at a supply story because my supply story can’t be falsified?)

It would be a big job to try to gather all the data, but it would be interesting to see if the other expensive countries had home prices that moved on cantilevers like they have in the US - with the bulk of these increases coming at the expense of the poorest residents of their most expensive cities.