What's Driving Home Values (Part 4)

Building a properly supply-focused housing sector POV

In Part 3, I laid out 3 factors that you can use to account for aggregate real estate values.

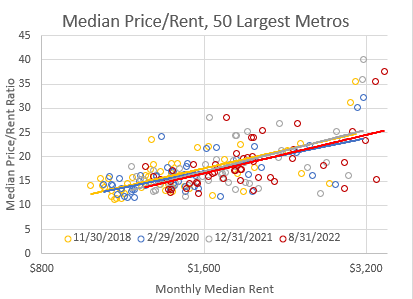

(1) Values in a typical city with adequate housing, which should be relatively stable. The left end of the regression lines in Figure 1.

(2) Higher prices that are proportional to higher rents, wherein outlier cities that have excessively high rents because of supply constraints have become much more expensive than average, and pull the average higher. The length of the regression lines in Figure 1 on the x-axis.

(3) The positive interaction between higher rents and higher price/rent ratios which pushes prices even higher in the outlier cities. The slope of the regression lines in Figure 1.

As I mentioned in Part 3, Factor 1 should be relatively stationary. Factor 2 is measurable and slow moving. That leaves Factor 3 as the only mystery to solve to explain how much excessive valuation there is in American real estate. Without supply constraints and high rents, aggregate owner-occupied real estate would chug along at about 80% of GDP. It would be boring. Real estate values really would mostly come from idiosyncrasies and hew to the old saws about location, location, location. I wouldn’t need to bore you with these substack posts. And no amount of Fed stimulus, GSE financing, low interest rates, or crazy-eyed speculators would be able to change much about it. Those things certainly wouldn’t be able to push aggregate real estate values to 160% of GDP.

Before I look at the older data, I think it may be helpful first to look at our current, broken market. Since the market is broken, and Factor 1 has ceased to be stable, the market is flipped on its head. Rent inflation is now rampant everywhere because housing production has been unsustainably low for more than a decade. Now, there is no left end of the regression line in Figure 1. Every major metro has inflated rents, inadequate supply, and aggregate real estate values that reflect that.

One could be forgiven for thinking that interest rates have been important, and that the sharp rise in interest rates is likely to crash the market. In Figure 2, I compare the average price/rent ratio of the 50 largest metros and the 30 year mortgage rate (inverted on the right hand axis). The mortgage rate is lagged 12 months (the rate from March 2019 is lined up with March 2020) because that seems to create the best fit. If future price/rent ratios follow rates, that suggests that something like a 20% decline is baked into the cake.

But, take a look at the evolution of the 3 factors since 2018. In Figure 3, I compare the price/rent ratios at 4 points in time. (1) November 2018 when rates previously peaked, (2) February 2020 before Covid struck, (3) December 2021, the last month before rates started to rise sharply, and (4) August 2022 after the sharp recent rate increases.

Remember, the interaction where interest rates might play a role is the slope of the line - Factor 3. Yet, in terms of both Factor 2 and Factor 3, the price/rent regressions at all four points in time are practically on top of each other! There is no discernable change at all, even though the average price/rent ratio in these metros increased from 15 to nearly 19 during this period! The regressions neither lengthened along the x-axis nor steepened. And, really, if each regression line was extended to a stationary rental value at the left end, of say, $1,100 or so, give or take $100, Factor 1 hasn’t changed much either!

Right now, you’re probably saying, “So, Mr. Smarty Pants, Mr. ‘my three factors explain aggregate home prices’, price/rent ratios increased by 20% and your precious factors tell us bupkus!”

That’s because we broke housing. There is no left end of the affordability scale any more. No city builds enough. Every city has elevated rents. Now, rents don’t explain everything because of the outliers. Now, rents explain everything because they are too high everywhere. Effectively, all the price gains since 2018 have been through Factor 2. There just aren’t any fundamentally affordable cities remaining as anchors to the price/rent line.

(Just to reiterate what an outrageous situation this is, I will remind you that, according to BEA estimates, per capita real housing expenditures are flat since 2008, in a sharp shift from historical trends. So, our construction industry is at capacity, all of our major cities have rent inflation that reflects systematic undersupply, and rent keeps taking more of the average household’s income, and we didn’t even get any more housing for it. And, while I’m thinking about that, it occurs to me that it’s a pretty strange market if stimulus, low interest rates, etc. are driving prices higher, and yet it doesn’t manage to increase the per capita housing stock in the process. In 2007, John Taylor told Federal Reserve officials that low interest rates in the previous few years had led to a million extra homes. I would argue that that perspective was wrong then, too. But, I wonder, is there a demand-driven explanation for cyclically high prices that deals seriously with that question? Does John Taylor lay awake at night wondering why we don’t have millions of extra homes today? Or does he think we do?)

Here, I’m going to commit a couple of minor chart crimes. In Figure 4, I have retained the price/rent plots for November 2018 and August 2022. As in some of the previous posts in this series, I’m going to mix those cross-sectional plots with a sort of time-series plot. Here, the black dots are the unweighted average rent and price/rent ratio of these 50 metro areas over that period, from 2018 to 2022. The average rent increased from $1,500 to $1,960 over that time, by Zillow’s measure, even though general inflation should have been associated with an increase of only about $200. I am just showing them here in nominal terms. But, in fact, adjusting for inflation using the GDP deflator puts the 2022 line just about right on top of the 2018 line, with just a slightly higher slope (the inflation adjusted slopes would remain the same as in Figure 4).

What you can see with the average price/rent ratios in Figure 4 is that the significant climb from an average price/rent of 15 to more than 18 from 2018 to 2022 didn’t involve any significant deviation from either the 2018 or the 2022 price/rent norms. Rents have been rising, and as they have risen, price/rent ratios rose in precisely the same proportion as they rise in the cross-sectional differences between metro areas at any given time. Cities with median rents of $1,500 or $1,960 have the same price/rent ratios today that cities with median rents of $1,500 or $1,960 had in 2018. It’s just that the cities have changed. $1,500 cities became $1,960 cities.

Now, to nudge the chart crime just a bit farther, I’m going to add a scatterplot (in green in Figure 5) which tracks the average rent among these metro areas each month on the x-axis, just as with the black plots. But, the y-axis (on the right in Figure 5) is the 30 year mortgage rate for each month, inverted, to give an indication of the effect of interest rates on prices. If interest rates are primary, then the black dots should be chasing the green dots down.

The two explanations - (1) a positive feedback between rents and price/rent ratios or (2) a standard interest rate explanation - produce surprisingly parallel results until this year. (I have not lagged interest rates here.) And, then, they suddenly diverge. And, so, again, there is a binary choice. Are interest rates going to tank home values so that home values move far outside the normal relationship with rents that now has a twenty year history? Or, will home values maintain the regular relationship with rents and interest rates won’t matter much?

It is a two-step retort to interest rate worries. The worry is that since the interest rate peak of November 2018, home prices have increased by nearly 50% against general inflation of about 14%, and it coincided with a period of low interest rates that recently spiked back up. But, (1) market rent inflation was 30% over that time, and (2) market rent inflation correlates with a higher home price of something like 50%. If these price and rent relationships mean anything, then low interest rates were never actually associated with an unusual increase in prices, and so there is nothing for high rates to reverse.

Pick a model. And, whichever model you pick, you have to break the other model. I suppose one could try to reconcile this by saying that higher mortgage rates will lower the slope of the line, and the line is really tethered at $1,200 monthly median rent, even though no cities represent that rent level any more. Maybe the price/rent line was only able to remain stationary because of low rates. So, maybe the price/rent regression line will level out in the low teens at the left and rise to the high teens at the right. That would reconcile the two factors (rates and rents would both be influencing prices). But, the last time mortgage rates were at 6%, the slope of the price/rent line was much steeper. I’ll look at that in future posts.

As a policy issue, also, there is little middle ground. If demand stimulators like low rates have been driving unsustainably high prices, then the correction will entail a slowdown. If rents have been driving high prices, then the correction will require a building boom.

Jerome Powell seemed to suggest that he is on team slowdown. Yesterday, Reuters reported:

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell on Wednesday said the U.S. housing market will probably go through a "correction" after a period of "red hot" price increases that have put home ownership out of reach for many Americans.

"There was a big imbalance ... housing prices were going up at an unsustainably fast level," Powell said at a news conference following the Fed's decision to raise its policy rate by another 75 basis points. "For the longer term what we need is supply and demand to get better aligned so housing prices go up at a reasonable level, at a reasonable pace and people can afford houses again. We probably in the housing market have to go through a correction to get back to that place."

The Fed's rate hikes this year have had their biggest impact on the housing sector, slowing sales and bringing prices a bit lower. Shelter inflation will remain high for some time, Powell said.

Two years from now, where should a “corrected” black plot and green plot be on Figure 5? Where do you think they will be? Where does Jerome Powell think they will or should be? (One caveat in defense of Powell seeming to expect rising rents and declining prices is that the shelter inflation measures the Fed uses significantly lag the Zillow measure. It’s odd that his focus on backward looking data might give one solace, but here we are.)

All in all, I think Powell has steered the ship well so far. In 2007-2008, the Fed, in effect, tried to lower our incomes to match our stagnant housing stock. His language here suggests that a demand-centered explanation for housing costs is leading them in that direction again. Fortunately, (again, an odd sentiment, but here we are) the housing market is so broken that I expect a lot of other things to break before the demand for housing moves much below our capacity to build it, so that the Fed will have to relent and change course much more quickly than in 2007, probably before home prices decline much and before construction activity has much room to “correct”. When the Fed does relent, I suspect the general sentiment will be that other people have too much credit or income rather than that all of us have too little housing. Some will demand recession again if that’s what it takes to push home prices down, and the Fed will not be popular if it avoids one.

On the bright side, surely the supply chain constraints will, at some point, allow construction to expand again, and maybe home prices will normalize for the right reason (and probably for the only reason that is attainable and sustainable) by sliding back down to the left end of the price/rent slope. That is likely to be a slow process, if (cross your fingers) we can manage it.

Kevin, thanks for this--it's a lot for my small brain to process, so I'll try to be focused with my comments and questions. I'm hoping this time will be different than 2008-2012 when Fed policy slaughtered housing starts. Is it fair to say that current policy is acknowledging that housing will have some temporary damage but will recover after 2023?

So are you long home builders and housing REIT's?