The Base Case is Optimistic: Homebuilders

Following up on the previous generalized post about business cycle, in this post I want to address homebuilders and the construction industry, specifically.

The analysis must start with this chart from a recent post. This is the real per capita consumption of housing over time. Real housing consumption, per capita, increased in a dependably linear pattern until 2010, and then it went flat. (Actually, 2008 is probably the more appropriate breaking point, as 2010 was well below the 1960-2008 trend. And, isn’t it wild that the conventional story of the 2000s is that we overstimulated and overbuilt housing? Real per capita housing consumption, even in 2005, was below any trendline you could have drawn leading up to that decade! The only way to have such a bloated housing market, as we have again today, is to not have enough of it!)

A couple points on this chart.

First, there wasn’t a sudden cultural turn from housing demand. There was a financial crisis and a massive regulatory imposition on lending that most people still prefer to ignore or excuse.

Second, population growth, demographics, etc., don’t really matter much for this measure. There are some minor changes in per capita housing consumption that change over a person’s lifetime. So, there are shifts in per capita housing consumption that are likely demographically related. Since the 1960-2010 period included some pretty sizable shifts in several demographic trends, you can infer the scale of those sorts of changes from the chart. Relative to the change after 2010, they are noise.

Third, if we just extend the naïve linear trend from 1960 to 2010 up to the present, real per capita housing consumption is about 14% below trend. Owner-occupied real estate today is worth about $41 trillion, so that would equate to a little less than $6 trillion in residential investment to get back to the 2010 trend. In terms of units, there are currently about 144 million homes in the US. So, about 20 million units would get us back to the 2010 trend, all else equal. Current residential investment is running at about $1.1 trillion annually. So, that would be about 5-6 years’ worth of residential investment. That makes sense, since for more than a decade, housing starts have been running at about half the previous pace.

20 million units, worth about $6 trillion, to re-attain longstanding consumption patterns as of 2010. (Economists with the Congressional Joint Economic Committee actually came up with a similar estimate using a different, more sophisticated, reasonable statistical approach.)

The 2010 level was already below the previous trend. From the 1970s to 2010, real housing consumption declined from its previous trend, but total spending (i.e. rental values) increased above the previous trend. Even the 2010 level of housing consumption was constrained by arbitrary urban land use regulations. We were paying more of our incomes for less and less home, even before 2010. So, 2010, itself, was about 14% below the trend of housing consumption from the mid-20th century, when housing supply was still not so politically constrained.

I’m not saying we need $12 trillion in residential investment or 40 million additional units, or whatever the form of supply would take to get us to the mid-20th century norm. But, I am saying that it is likely that if we had all those homes, we would have no trouble finding someone to buy them, rent them, hold them for occasional use, or whatever those marginal new housing consumers were doing in the mid-20th century. And, we sure as hell won’t have any problem finding someone to put the first 10 or 20 million units to use.

Second, if you think there was some cultural change in 2010, and Americans just happened to choose to stop wanting more home at exactly the same time that the average credit score on approved mortgages shot up by 40 points, then, more power to you. But, even if you aren’t ready to follow me to 40 million units, I think that if you expect residential investment to decline from the current level, so that per capita housing consumption would need to decline, in real terms, then I think you are taking a much more extreme position than I am taking. And, yet, you really would have to be taking that position to be selling American homebuilders at today’s valuations.

Third, from a policy perspective, to me, the graph above is one of those “ah, ha!” graphs. It’s just such a shift from such a narrow and long trend. I am a full-throated YIMBY. Reversing overregulation of land use is imperative. But, really, that explains the trend-shift from before 1980 to after 1980. You can see it. It amounts to a lot, cumulatively. But it is dwarfed by what happened after 2008, which just happens to have coincided with a very sharp tightening of federal mortgage lending oversight, and which shows up in countless ways in the data. (For instance, in the credit component of my housing tracker, which is measuring something totally different from real per capita housing consumption.)

Fourth, this doesn’t mean that I think in a couple decades, after $5 trillion in additional residential investment, aggregate real estate will be worth an additional $5 trillion. In fact, it will be worth less than it is today and total rental expenditures would be less than they are today. More than 100% of residential investment, in our current constrained context, goes to consumer surplus. It’s all free and then some. I’m not sure exactly what that means for property managers and owners, but it doesn’t matter so much for homebuilders. In any case, they would be busy building and selling millions of properties at something in the range of their normal profit margins.

So, there are several ways to position yourself based on these observations. If you think real housing consumption will remain constrained, property owners and managers may provide excellent returns. To my mind, the homebuilders have both limited downside and extensive upside because either rental values (and property values) will continue to rise, or we are set for a significant building boom relative to today’s construction activity. And, it is hard for me to imagine a construction level much below where it is today. It would require a hard turn to Japan level population trends, combined with a continuation of supply constraints, mortgage overregulation, and stifled immigration.

So, that’s the long-term setting for homebuilders. What about cyclical issues?

This is a novel cycle we’re going through, and so it isn’t easy to think through some of this stuff. I’ve written a bit about the odd market we are in now, and the ways that traditional readings of the data might be difficult to understand in today’s context.

Migration

The recent American Homes 4 Rent conference call has some interesting color. The AH4R executives had this to say on migration. “I mean specifically, one of the major drivers, migration into our portfolio is out of California. And even on a year-over-year comparative basis, it is still up 30%. So that has not stopped. It is not slowed down at all. And it has a big impact on our Western markets. So that is continuing.” Of course, secularly, this is terrible, but cyclically, it is bullish.

On the other hand, in the last few weeks, I have noticed that U-Haul rates from LA to Phoenix have decreased. Earlier in the year, a 20’ truck would have cost more than $1,100. It’s now down to under $700. From Phoenix to LA, it’s only a bit above $200, so the flow is still strongly out of LA, but it is a trend that bears watching. If migration into growing cities dries up, that would certainly risk creating sharp reversals in some of the cyclical price appreciation those cities have seen (though not the supply-related price appreciation which amounts to much more in most cities).

Prices

On costs there was this question and answer: “Did you say that you are starting to see outright declines in construction costs? Are you already seeing either labor and/or construction bids come down?”

“Yes, we are... But it is in the construction phases that are up through the drywall phase. We haven’t seen it in the post drywall, the finished trades, the cabinetry, et cetera. And there is still a significant demand for those trades by the builders. But the pre-drywall trades, we are getting inbound calls from vendors looking for work. And we now have the ability to be bidding multiple vendors or more vendors against one another, and it is benefiting in reductions. So anywhere from single digits to low double digits at this point. But I do expect it will continue to go up. And if you go back to historical trend lines and trend it and take out the pandemic aberration, there is 20%, 25% reductions to get back to the trend line of what construction has historically been.”

That scale of price aberrations is also reflected in the BEA’s price deflator for residential investment relative to the overall GDP price deflator.

This is an interesting situation for builders, because there could be a 10%+ price decline in new home sales, and it would only marginally effect builder bottom lines, and it wouldn’t be associated with the sort of systemic price collapse that we saw in 2008. In fact, as I outlined in some earlier posts, I think there is some distance between the triggers for these sorts of cost-based price decreases and the sort of decreases that are associated with a collapse in demand that would be strong enough to create an inventory overhang.

I think this will be a place where a bullish position could profit from the over-reaction some market participants might have to initial cost-based price drops. It won’t be “2008 all over again” but many will not make that distinction. This is an unprecedented situation, so there are questions. How much will prices decline versus fudging the price with rate buydowns, free upgrades, etc.? If new home prices do decline, how much will that bleed into existing home markets? How confident can we be that there wouldn’t be contagion from these sorts of price drops to price drops more similar to 2008 which would start to push down builder margins?

From a policy perspective, this is tricky, because clearly the price inflation in residential investment was not good, so it is fine, even good, that these markets are normalizing and trade contractors are competing on cost again. There is no reason to push construction activity down any farther than that, but micromanaging the supply chain with monetary or macroeconomic policy is asking a bit much. So, this will be interesting to watch. There will invariably be slack in some parts of the supply chain while others are still bottlenecked at capacity.

My current expectation is that activity will stabilize in the upstream construction trades as costs normalize. If it doesn’t that could be a sign of trouble.

Moving to another recent quarterly call, the homebuilder Meritage also talked about recent concessions on price (or some alternative, like rate buydowns). They also mentioned that late-stage trades were still dealing with capacity constraints while early-stage trades were starting to see some slack. So, their description of the current market was in line with the unwinding of the capacity condition back toward regular costs and margins - de facto price reductions from a few percentage points to mid-teens, which they are willing to do to keep a sale, on properties that were sold with above average margins and high cost expectations.

They are describing a price decline down to the right end of the “normal” range, which is a long way from the left end.

Sales & Cancellations

Meritage reported a year-over-year decline in net sales of 33% in the 3rd quarter, ending in September. This is the first quarter where they have reported elevated cancellations, so about 1/2 of the decline was due to cancellations.

Thinking about the current market using Meritage’s results, there are several reasons to consider the 3rd quarter sales level to be more bullish than that net sales number suggests.

This spike in cancellations likely reflect a rate shock, in which funding constraints have become binding for some buyers. This quarter likely was the peak for homes that were finished in a much higher rate environment than they had been sold in, and with construction timelines that prevented lower rates from being locked in. Cancellations could be high next year, too, if a recession develops, but that would be due to policy decisions that happen next year. The homes finished in a quarter or two will be homes that were sold with mortgage financing already at 4%, 5%, or higher. Those buyers won’t have the same funding shock. The convention to subtract cancellations from the current period’s gross sales is generally reasonable, but in this case, I think cancellations reflect a one-time event and gross sales are more informative.

The backlog is still strained, and Meritage, like most other builders, just doesn’t have very many move-in ready homes for sale, even with the added inventory created by cancellations. So, the continued supply chain issues limit sales growth. In 2021, the supply/demand mismatch was so great that the builders were metering sales, and now it is more likely that it is the customers holding off on buying activity - for instance, being unwilling to sign a contract for a house with several months of work remaining while interest rates are uncertain. In either case, sales aren’t being made even where demand, at some level, exists.

This is still a strong sales level. Gross sales in the 2022 3rd quarter, with 6% mortgage rates, were still higher than pre-Covid sales at lower mortgage rates. The rate shock has shook some marginal buyers out of the market, and some of those had to exit through cancelled orders, but the demand from new buyers signing contracts at these higher mortgage rates is still relatively strong.

Backlogs, Inventory, etc.

Meritage did slow down starts considerably this quarter, because of uncertainty about future demand. They only have about 300 completed, unsold homes, which is only about 6% of their unsold inventory. Construction times are still 6-8 weeks longer than usual. So, we are in a strange space with both supply chain constraints and concerns about trends in demand.

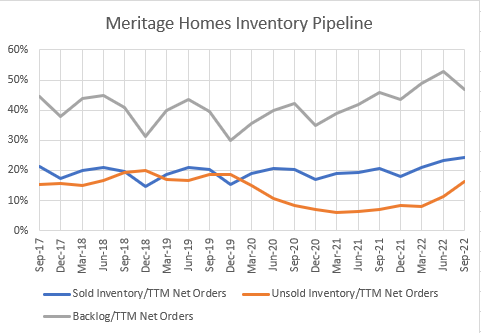

To think about that, here is a chart of Meritage’s inventory levels as a percentage of trailing twelve months net new sales. Figure 4 compares three measures. The backlog, in gray, is the sales value of homes that were sold but not finished. Before Covid, that tended to be about 30-45% of a year’s sales. In other words, a little less than 6 months between the typical sale and completion of the unit. The blue line is the amount already invested in the construction of homes in that backlog. The orange line is the amount invested in homes, either finished or under construction, that had not yet been sold. Before Covid, Meritage maintained an unsold inventory just about equal to the sold inventory that was still under construction.

You can see very clearly here the effects of the several sharp changes in various market trends. New home sales suddenly shot up in early 2020. The first effect was that buyers were claiming the unsold inventory. By the spring of 2021, the unsold inventory was basically bought up, and builders lacked the capacity to build more because of supply chain problems. It was then that rent inflation started to spike, and prices rose the most steeply, and instead of increasing throughput, builders could only increase their backlogs.

This has partially reversed. The value of work-in-process in unsold inventory is nearly back to pre-Covid levels. And, both prices and rent inflation are stabilizing as that happens.

Analysts have a wide range of expectations, but the average for Meritage in 2023 is revenue about a quarter below 2022 and earnings per share about half of 2022. All things considered, that’s probably not unreasonable. Expected earnings of about $15/share puts the current share price of about $74 at a forward price/earnings ratio of about 5. So, the valuation (which is typical of homebuilders) doesn’t just seem to assume a significant drop-off in sales next year. It also appears to incorporate a pessimistic outlook going forward. And that pulls us back full circle to Figure 1, to consider what the range of possible future changes is for housing expenditures per capita, and whether $74/share for Meritage fits within that range of scenarios.

(I looked at Meritage here because they recently announced quarterly earnings. This is not investment advice, and I do not have an opinion regarding the relative value of Meritage compared to other homebuilders. Many other builders would produce similar analysis in terms of trends and valuation.)