Unfortunately, production efficiency isn't going to make housing affordable

There are some new modular homebuilding ventures out there. This sort of incremental innovation is important in all markets, and it could be important in housing. We should hope that it can be important in housing. But, frequently, these new homes are presented as a solution to the housing affordability problem, and I’m afraid that is not as likely as it seems. Two high profile firms have failed. I don’t follow the operations of these firms closely, but I wonder if the failures have to do with the disconnect between their mission and the problem with American housing markets.

Regulated Away

Why isn’t there more modular housing already? As James Schmitz, Jr. at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis as pointed out, we don’t currently have an active modular housing market because of an excess of legislation, not a lack of innovation.

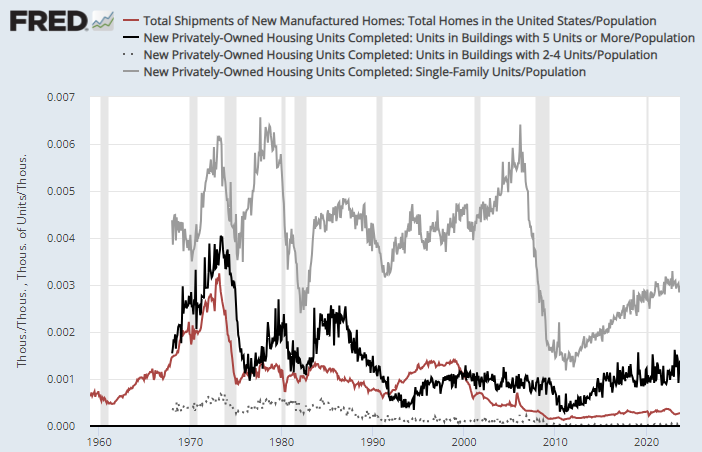

We didn’t lose the technology to produce manufactured homes after 1974. We effectively outlawed them. As shown in Figure 1, their decline was on par with the decline in apartment construction.

Occasionally, I see an article about 3D printed homes. I half-joke that California will soon pass a law requiring all homes to exist in 4 dimensions.

The problem new modular and manufactured homes must solve is arbitrary local and federal regulation.

Some Limited Regulatory Potential

One area where there might be potential for inroads is for casitas, or accessory dwelling units. This is still a regulatory issue. But, if streamlined and uniform rules can be disseminated among major metropolitan areas, maybe these products could be a functional and affordable way to add small units to existing lots.

As figure 1 shows, though, 2-4 unit lots have never been a particularly large part of housing growth. They probably are a sort of canary in the coalmine. A city with functional land use regulations will tend to allow them, so that they are one arrow in the quiver of potential housing development. Like VanHalen checking for brown M&Ms in the green room, a lack of ADUs probably means a lot of other things aren’t working well.

But, cheap ADUs with modular buildings probably can’t move the needle that much on broad affordability.

Possibly, increasing the quality of “mobile home” type homes might reduce some of the opposition to their approval. Again, though, the innovation wouldn’t really be directly about costs as much as it would be about changing the sentiment that leads to obstructionist regulations.

Can there be a housing supply problem if houses are larger than they used to be?

Finally, I want to parse out a little bit why cost of construction is not a particularly useful vector for fixing American housing.

One frequent point that housing supply skeptics make is that the average home is larger than it was, say, 50 years ago, and the average household is smaller. If square feet per capita is substantially higher, then how can we say that a lack of housing is the fundamental problem that is driving costs so high?

There are several problems with this line of thinking.

First, it hasn’t really been true for a while. Per capita real housing consumption hasn’t increased for ten years. The average size of new units hasn’t increased for twenty years. And most of the drop in average household size happened more than thirty years ago. So, the skeptics are using mid-20th century changes in consumption to argue against a problem that has been most acute in the 21st century.

Second, even if we accept that the typical American has more space than their grandparents did, this is not a standard we would apply to any other form of consumption. Would you consider something like, “Real incomes for group x have not grown for 30 years.” to be a clear signal of a problem? “Real per capita consumption of housing has not grown for 30 years” is no different. It’s not a reasonable benchmark, and if it was true, you should expect people to be just as upset as they would be about having stagnant incomes for 30 years.

Third, the housing problem is not uniformly experienced. There are basically three types of households in an economy.

Households in regions with adequate housing construction will sort among the new and existing stock of housing such that they all tend to live in homes whose market prices are around 3x to 4x household incomes. (Of course, if public poverty support is given in kind or through targeted vouchers instead of through cash, then some small percentage of households with very low incomes will live in subsidized housing.)

In regions with inadequate housing, households exist on a gradient between two extremes. Households with the highest incomes will consume less housing while spending the normal amount of their incomes on it. Households with the lowest incomes will spend more on housing until the only remaining solution to rising costs is to move out of the region to a more affordable region. Every household exists on a gradient between those two extremes.

So, distortions to housing consumption are not symmetrical. Higher costs are mostly experienced by the poorest existing residents of the most expensive cities and less real consumption of housing is mostly experienced by the richest residents of the expensive cities.

Figure 2 compares the median home price in 4 ZIP codes. Two (the black lines) are from Los Angeles - one in Beverly Hills and one in Compton. Two (the red lines) are ZIP codes in Charlotte, North Carolina. One with higher incomes and home prices and one with lower incomes and home prices.

To aid in a comparative analysis, Figure 3 shows the price/income ratio of the median home in these ZIP codes from 1998 to 2022.

Let’s consider the question of whether Americans are spending more on housing because the homes are larger than they used to be. How does that play out here? I don’t have residents per square feet data on these ZIP codes, but I think we can infer that it is negatively correlated with the price/income ratio. Where price/income is lower, square feet per resident is higher. From most to least square feet per resident, the likely order is: (1) rich Charlotte, (2) Beverly Hills, (3) poor Charlotte, (4) Compton.

What about over time? From 1998 to 2019, price/income ratios were relatively unchanged in Charlotte. They rose 50% in Beverly Hills and doubled in Compton. Is that because a massive amount of square footage was added to the Los Angeles market? Do Compton residents have an overdeveloped sense of entitlement about housing?

In the last few years, the poorer Charlotte ZIP code and Compton ZIP code have both become much more expensive while the wealthier ZIP code prices were relatively stable. Again, is this because we have been adding a lot of square feet in low tier neighborhoods?

One might think, with a moment’s thought, that the big valuation pop in Compton in 2005 was from building. There was a lot of construction in 2005, and a lot of it was in low tier markets. But, not in Los Angeles. Cities like Charlotte were where the building boom was.

Let’s think about movements and migrations within and between these ZIP codes. In high tier ZIP codes like Beverly Hills, where costs are higher than they are in high tier Charlotte, families who might have have 2,000sq ft/member in Charlotte instead settle for 1,500 or less. They do that by trading down within the stagnant stock of housing in the LA metro area, bidding up the rents and prices of lower tier homes. In Compton, the marginal movements into and out of the ZIP code might be families that would have 500 square feet per resident moving down to 200. And families scraping by with 200 square feet per member finally hitting the end of their ropes and moving to places like Charlotte, where they might have 500 square feet even if their costs are lower.

As I have noted elsewhere, the population of the cities that lack adequate housing is negatively correlated with both housing construction and home prices over time. When these intra-metro substitutions and competitions for housing heat up, it is the families that can buy more who win the game of musical chairs. Outmigration increases during those times. So, statistically, you could associate the spikes in home values in Compton with an increase in per-capita housing space. Families that can afford 500 square feet per member are outbidding the families hanging on to 200 square feet. Yet, every family in that exchange is compromising downward in some way - even the family displaced from Compton into a larger unit in Charlotte.

The family put in the worst position here - the family forced to move out of Compton - might just be the family that increases their real use of housing the most. Are families displaced out of places like Compton to places like Charlotte unaffected by a lack of housing supply? Are they just young families with an overdeveloped sense of entitlement because they would complain about high housing costs even while they contribute to aggregate statistics of more space per capita?

Wait, wasn’t this a post about modular housing and construction innovation?

My point here is that higher construction costs are completely unrelated to the real consumption of housing. In fact they are negatively correlated. And there is little direct connection between housing costs and cost of construction.

In addition to the population and migration patterns out of places like LA, the national numbers also show a negative correlation between cost and housing utilization. Rent inflation moves in opposition to real housing consumption at such a scale to make total nominal expenditures (money spent) on housing negatively correlated with real expenditures (size, quality, etc.) on housing. The less we get, the more we have to spend for it.

From 1998 to 2022, the median home in the Compton ZIP code increased from $100,000 to $570,000. That isn’t because the cost of construction quintupled. It’s because the price of a low tier LA location quintupled. The construction costs on that house are not the reason for its value inflation. The elevated housing expenditures in Figure 4 are mostly from places like Compton.

The American housing market is the aggregation of greatly varied and asymmetrical valuations across cities and incomes. More efficient construction will mostly increase the real housing consumption of families where supply is adequate and valuations are moderate.

Figure 5 is real PCE consumption and real housing consumption over time. The green line in Figure 4 is housing divided by total PCE (the blue line divided by the red line in Figure 5). Over the 30 years from 1963 to 1993, both total real consumption and real housing construction doubled, per capita. Americans were getting richer, and our housing scaled with that. For the 30 years from 1993 to 2023, total real personal consumption per capita increased by 72% while real housing consumption per capita increased by only 34% - and that increase was mostly before the Great Recession.

Thinking of this simply in terms of square footage, our incomes doubled and the relative sizes of our homes doubled from the 60s to the 90s. Then, after the mid-1990s, our homes only increased at half the rate of our real incomes. In the aggregate, that could plausibly be a productivity story. If construction productivity stagnated, then Americans would tend to continue to spend a stable portion of our total incomes on housing, but the housing wouldn’t be quite as nice or as large as it could have been. If construction productivity was normal until the mid-1990s, and then started to lag, the national aggregate housing expenditure charts (both real and nominal) would look like they do.

Construction productivity has been low compared to productivity in other sectors, according to some measures, but urban land use restrictions loom larger. One oddity to note is that low productivity growth in construction seems to go back to well before the 1990s, yet real housing consumption grew at the same pace as other consumption.

This is speculative, but I think this has to do with my point that generous mortgage lending and active homebuilding mostly lower rents on older units. The main benefit of Fannie, Freddie, and the FHA is to lower rents for non-owners. The most productive form of housing is the 50 year old home that already justified all of its material inputs, but is still providing healthy shelter.

In other words, there are two sources of productivity in housing: the productivity associated with construction of new units and the productivity, as it were, associated with the relative rent income claimed by the owners of old units. The relative rents claimed by the old units is probably much more important than the productivity of new construction at any given time. So, if quantities are ample, it may not matter that much how productive new construction is, because the extra units will lower the economic rents paid for depreciated homes, raising the real incomes of those tenants.

If construction productivity was the key shifter from the pre-1990s trend to the post-1990s trend, the aggregate spending trends would have been relatively uniform across the country. Basically, if construction had been much more productive, price/income ratios in Charlotte in Figure 3, before the Great Recession, would not have looked any different than they do. But, there would have been more housing. The new homes would have been larger and nicer. This would have accelerated the downward filtering of the existing housing stock. On average, everyone in Charlotte would have had better homes for the same amount of nominal expenditures.

In other words, more productive construction would have caused an uptrend in the blue line in Figure 5 but no change in trends in Figure 3.

But, clearly, cost trends have not been uniform. That is because the drop in real housing consumption and the rise in nominal housing expenditures and home values has been largely driven by urban land use rules. More productive construction wouldn’t have changed the trends in Figure 3 in LA any more than it would have changed the trends in Charlotte. There might have been a bit more construction in LA as a result of more productive construction, but housing costs in LA are driven by the asymmetry of nominal expenditures - rich residents being able to spend more than poor residents. High costs in LA are from land rents on the existing stock - poor productivity from old depreciated homes. The same processes would be in place, and nominal expenditures would still be driving price/income ratios in Compton to the mid-teens because that would still be the cost level required to motivate residents to choose affordable displacement over expensive stability so that someone else can have their old home.

This brings us back to new modular and manufactured homes. Since the motivation for these ventures is productivity, and since it seems intuitively obvious that the affordability created by higher productivity would be most appreciated by residents of low tier homes, their product focus tends to be very small and efficient units.

But that’s a mismatch from what our markets would demand. The productivity problem that is the binding constraint for low tier housing residents is the land rents they are paying on depreciated homes - the run-down, one-bedroom apartment that was renting for $1,200 five years ago and now rents for $2,000. Of all the markets in Figure 3, the one that will probably consume more as a result of more productive construction is the market with the largest homes - the high tier ZIP code in Charlotte. But, that’s probably not a development dying for new disruptive producers. It certainly isn’t a market that wants to buy up a lot of 800 square foot studio units that unfold on the site in a day.

I doubt that the new modular builders can do much more than improve conditions on the margin. As with most attempts to improve housing, it can really only help, on net, after the prerequisite is solved - the diminution of land rents that will come with more construction and less urban land use obstruction.

This was very good, and you get bonus points for the reference to Van Halen's quality trick.

By coincidence, at the same time you posted this, Construction Physics took a look at ways in which HUD standards could yield more construction productivity for ADU's and other small housing types. I should really rant about that on his blog, but I want to point out there was never really a golden age of modular construction. HUD conforming trailers, mobile homes, etc.... are not an architectural solution for housing except for the most desperate of circumstances. I will maintain that position and object to the way they've been treated from the perspective of land use regulation.

Maybe too early to crow yer, but maybe time to spay throat tonic and step up to the podium.

"Inflation in the US, as measured by the change in Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index, was 3% on a yearly basis in October, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis reported on Thursday. This reading came in line with the market expectation and was below 3.4% of the previous month.

The annual Core PCE Price Index, the Federal Reserve's preferred gauge of inflation, rose 3.5%,"