More on House Sizes and Costs

In the previous post, I discussed trends in new home size. Here, using Census data from the quarterly residential construction report, I can track new home size back to 1974 to add a little more depth to the trends.

If we use a basic but biased way of looking at housing production (Figure 1), there was an unprecedented housing boom in the 2000s. The US briefly added new square footage at a rate roughly double the previous norms.

But, as we do with most economic indicators, we should adjust for growth over time. Figure 2 presents the additional square feet of residential space added per capita. (This doesn’t account for homes lost from the existing stock.) With this adjustment, the 2000s boom is still larger than the previous booms, though not by as large a scale.

Using a very broad estimate of the square footage used for new population growth, in Figure 2, I estimate the relative amount of gross new construction that increases the sizes of existing homes versus providing new homes for new households. Here, the peak of new square footage for existing households in 2006 is just a bit larger than the peak in 1978. By these estimates, the current housing market is providing a small amount of new square footage for our currently very low population growth, plus new square footage per capita that is similar to the average from 1974 to 2007. This follows a decade of record low construction per capita.

Figure 3 shows the average new home size since 1974 for single family, multi-unit, and the total average. The average unit size in 2022 was similar to the average unit size in 2003. That’s 2 decades with no growth in the average new unit size.

This is a combination of three factors. (1) single family homes that have increased in size somewhat, (2) multi-unit size that has declined, and (3) a compositional shift in which a larger portion of new units are multi-unit.

The third factor makes the decline in multi-unit size more remarkable. Increased market share for multi-unit should mean that they are expanding into families with more members, higher incomes, etc. That should be associated with higher rents, larger units, etc.

As I highlight in my work, mortgage suppression since 2008 has divided families into haves and have-nots, depending on access to mortgage financing. Those who have lost access have been hit with a regressive amount of rent inflation and they have responded with a deep decline in the quantity of housing that they demand.

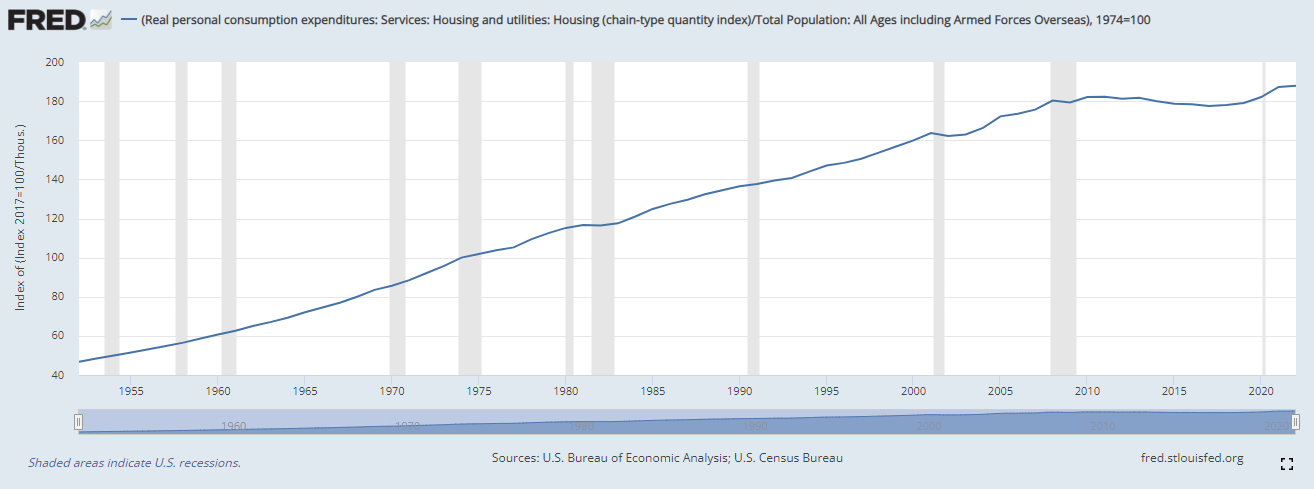

I have pointed out elsewhere that real per capita consumption of housing has flatlined since the Great Recession. (Figure 4)

This has probably been one of the most momentous shifts in relative consumption patterns in generations. (Figure 5) I write a lot about filtering here. (“Trickle down”, if you’re nasty.) It is not an accident that when a lot of larger homes were being completed, it coincided with a decline in housing costs for the poorest families and when fewer and smaller homes were built, housing costs went up for the poorest families. The richest families have never had it better.

One of the shibboleths of supply-skeptics is that there can’t be a housing supply problem because the average home is much larger than it was 50 years ago and the average household has fewer members. That was a legitimate story to tell in 1993.

Average household size has leveled off as average unit size has leveled off. The average square feet per capita in new homes is lower today than it was in 2007. This is a shocking turn of events because incomes are rising, and as Figure 5 highlights, for most families their housing expenditures are rising as a percentage of those rising incomes! As Figure 6 shows, families were increasing their consumption of housing regularly until the Great Recession, and then we broke it. Keep in mind, this is the average size on new units. This only changes the average size of all homes on the margin, as most homes were built decades ago. The size of the average house in the whole stock of homes changes more slowly. As Figure 4 shows, the previous trend dates back decades.

Unfortunately, there is a sizeable population that will never let go of their demand-side explanations - blaming the Fed, or federal mortgage programs, or private equity, or speculators, or whatever. But there is just no justification for focusing on anything but supply here. Americans, year after year, are paying more and getting less housing. Solving this problem will require a plurality of realists to overcome both the urban land use NIMBYs and the anti-demand permabears.

Figure 7 estimates how many square feet of space the average family claims for each $10,000 of income. This is adjusted for inflation, so the benchmark expectation here should be flat over time, and that’s roughly how it was for 30 years leading up to the Great Recession. Now, each square foot of new space costs more, in real dollars, than it has since records have been kept.

As I discussed in the previous post, I think much of these higher costs are related to higher development costs and land costs that are associated with urban land use obstructions. And, even though home prices declined after 2007, households still claimed less square footage per dollar of income than they had previously.

The demand-side permabears won the policy debate in 2008 by a landslide, and our economy lost. The post-2007 economy was the result of attempting to make ourselves poor enough to fit with our crappy housing stock.

Over time each square foot has become more expensive. This is annual data. So far in 2023, costs have corrected back down toward $200/square foot, and I suspect they will decline a bit more as we exit the supply chain constraints associated with Covid. So, much of the recent surge will be temporary, but there is an upward trend.

Paying more and getting less for it is the signature of a supply constraint, and there should really be no debate about it. Fifteen years ago, a supply skeptic need to take an ascetic position against growth - a country with higher income and more productivity shouldn’t be expected to increase its consumption of housing proportionately. Today, a supply skeptic needs to take a position against empirical reality.