Home Size and Costs

Are some new home buyers downsizing because high rates are creating affordability challenges? Almost certainly.

So, what now? Nothing much, really.

I have touched on home size, prices, and mortgage rates recently. In light of the previous post about sources of demand, I thought maybe another post on this could add a little bit of color to the idea.

Size of New Homes

First, the national average square footage of new homes is a complicated measure. I haven’t tried to methodically model it. It is influenced by a number of factors, many of which are compositional (a change in the set of units that are being compared). They include:

The scale of new building, part 1. After 2008, new single-family housing starts dipped by 75%. It’s still only half the 2005 peak. The “extensive margin” is probably at work here. High tier homes tend to get built in all markets, and as construction expands, it expands into lower tier buyers. So, the decline in average size from 2014 to 2018 might be related to the slow recovery in housing starts. I suspect that this was reducing the average size before 2006 also, but it was outweighed by other factors.

The scale of new building, part 2. Expensive cities where units tend to be smaller are expensive precisely because there is a cap on the level of new construction that gets approved. So, as construction expands, it expands more in cities where homes are more affordable and tend to be larger. This was probably increasing the average size of new homes before 2006. But the growth of affordable cities has been stunted by mortgage suppression since 2008, so this has been less of a factor since then. In other words, since 2008, a higher proportion of new homes are for families that buy larger homes, but a smaller proportion of them are in cities where families buy larger homes.

Financial distress. From 2007 to 2011, there was a financial crisis that just lowered the ability to purchase homes across the board.

Economic growth. Americans generally tend to increase the sizes of our homes when we are doing well and decrease them when we are not. This creates a wave shape rising during expansions and declining around recessions.

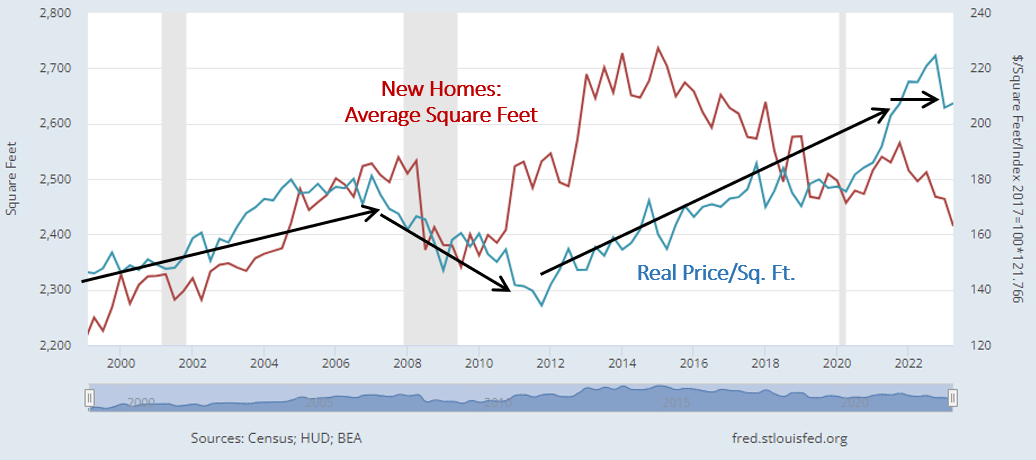

As I mentioned in the previous post, when housing is blocked and homes get more expensive, more of the value comes in the form of amenities and location premiums. Families have to trade off the shelter component of housing when they pay more for those other elements. In previous decades, Americans were increasing the square footage per person on new homes by 15% to 20% per decade. From 2,300 square feet in 2000, that trend would have gone to about 2,650 by 2010 and more than 3,000 by 2020. Had the building boom of the 2000s continued, we might have gotten close by 2010, but the expansion of the supply problem has pulled new home size well below trend. The average size of a new home today is smaller than it was in 2006 and 2007. Mortgage rates today are only just a bit higher than they were then. That’s a decade and a half with no growth in the average new home size.

Mortgage payment constraints. I’m willing to stipulate that some portion of the 100 square foot decline since early 2022 is related to rising mortgage rates and payment constraints. During this period, the shift in rates was so large that it might have actually had some small measurable and predictable effect on this particular outcome. This is a temporary deviation from the norm of rates not mattering.

I should be clear. Mortgage rates have large effects on real estate broker activity, refi mortgage lender activity, etc. I don’t mean to make light of those challenges. It’s just that those things are tertiary to the focuses of this newsletter. And, I suspect that since they are important to those activities, and there are conceptual reasons to presume that rates are important generally, in various ways, they are overestimated as a causal influence on construction activity and prices.

Frequently, I think, in the realm of complex ideas, the more wrong something is, the harder it is to correct. This is the challenge I have with my financial crisis historical revisionism. It’s such a large correction to the conventional wisdom that it takes a lot of work to consider it, because the revised history would require revising a lot of other observations and presumptions. So, I rarely get moderate feedback. Generally the reaction is revelatory, antagonistic, or, most often, an unwillingness to engage at the depth required to consider it. That’s understandable. If I was approached with the fully formed thesis, I’d probably be in that camp myself. It would be deep in my stack of open internet tabs.

Mortgage rates tumbled from 2007 to 2012 and again from 2018 to 2021. And, between those periods, remained at secular lows. Yet, that was the decade that new American homes stopped getting larger and they especially stopped getting larger when rates dropped. The idea that high prices and construction activity have been stimulated by artificial demand at all, and specifically that low mortgage rates were a source of that demand, is untenable. It’s so untenable, it would be too much work to even consider its untenability, empirically. So, it exists above the plane of facts.

That probably turns some readers off. I’m not sure how to say it. If you think mortgage rates are important to home valuations, then ask yourself, have you really taken the time to walk through the last couple of decades and confirm how prices and rates could have followed the trends they have if there was an important relationship? And, if any of you has a quantitative model or an idea of what other factors need to be controlled for in order to produce a time series regression that confirms an important role for mortgage rates in home values, I would love to see it. I have tried and failed. And, I will admit that when I look back at early writings of mine, before I focused on housing, to see what dumb things I might have written, my presumptive starting point for thinking about the 2000s housing bubble was that the elevated values of the American housing market could mostly be explained with interest rates. I have now looked more closely. I was dead wrong.

The average new home was 2,577 square feet at the end of 2018 when the 30 year mortgage rate was 4.8%. Then, when mortgage rates dropped to 3.1% at the end of 2021, the average new home size was 2,565. Today at 7%+, it’s at 2,415.

Have you ever seen a single bit of analysis that attempts to address any of the data trends that cast doubt on the importance of mortgage rates? I suppose that’s why it’s so common for mortgage rates to be treated as some sort of tool of the Fed, turned up or down as a causal mechanism that can heat up or cool off the housing market. I mean, if the facts are just vibes, the causal story might as well be whatever you want it to be.

The reason Florida is so dry and cold is because the elephant herds that follow the Gulf stream in their annual migration kick up dust into the atmosphere. If we had a federal committee in charge of moderating the Gulf Stream to affect these patterns, who are you to question them? If you can’t figure it out, it’s probably because you’re not accounting for the expectations channel and long and variable lags.

Price per Square Feet

Conceptually, we tend to attribute non-structural price changes to land value, but mechanically, when a builder sells an x square foot home for y dollars, those amenity values inflate the reported dollars/square foot.

Conceptually, the higher price of homes is due to the Metro Area Scarcity Premium and Endowment Premium that I discussed in the previous post. The reason home prices have generally risen relative to incomes is entirely due to obstructed supply and the willingness of locals to overpay to avoid regional displacement.

But, on the ground, where that intersects with new building, it flows through mandates, taxes, and delays imposed on builders. Where it doesn’t get captured through those channels, it flows to land values. On the builder’s spreadsheet, those all generalize to “higher costs”, and so from the builders’ perspective, this is a cost problem. (I have long been meaning to sit down and write a serious piece about that - about how the cost problem is downstream of the supply shortage problem.) And, on the Census Bureau’s spreadsheet and the buyer’s spreadsheet, all those costs funnel to “price/square foot”.

Just a bit more below the fold for subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erdmann Housing Tracker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.