Hovnanian continued the trend yesterday of testing object permanence in communal human perception. This was about the 98th homebuilder earnings announcement out of the last 100 that beat expectations on earnings with an increase in forward revenue and income guidance. Apparently this is still surprising to investors, so Hovnanian was up 15% on the day.

I’m of two minds on this. On the one hand, it is nice to see a position you’ve vouched for have a good report and a good trading day. On the other hand, Hovnanian is worth owning because it will probably eventually sell for more than $400/share, not because I thought the market would reward it for a good quarter. On the other other hand, it appears to have about 6 doubles in it from its lows around $6 back in summer of 2019, and it has already ticked off 4 of them, so I feel a bit uncomfortable taking a publicly bullish position on it, as it is a bit late in the game, exponentially speaking, to get on the HOV train. On the other other other hand, 3 of those doubles from the bottom are basically just a recovery from its deep 2018-2019 losses when it became a delisting/bankruptcy risk, so maybe 3 doubles were a reversal of going concern risk and on valuation grounds, this is just the first of 3 doubles. Or maybe there are no more doubles and I am overconfident about the valuation doubles because I was invested for the going concern doubles.

I’ve run out of hands.

Me going on and on about mortgage rates and construction activity

Anyway, why the surprise?

CEO Ara Hovnanian said in today’s conference call, “The doubling of mortgage rates during fiscal '22 caused the entire industry's home sales to fall substantially in the second half of the year. To spur sales activity, starting last summer, we and most of the industry offered increased incentives, which resulted in lower margins on new contracts at that time. As a result of those lower margins and the reduction in sales pace in the second half of '22, many of our third quarter profit metrics are challenging year-over-year comparisons.”

One reason these surprises keep happening is because the market believes in a myth. Fortunately, for Hovnanian, while they did slow down land buys in 2022, they didn’t slow down speculatively building homes during the 2022 sales scare, so they have the dry powder to keep pulling in revenue.

Mortgage rates are simply far overestimated, by both practitioners and theorists, as a housing input. Back in the 1970s when Fed policy became too inflationary, there was a negative relationship between mortgage rates and construction. Inflation would rise, and continue to rise as the Fed chased the neutral market rate up and down over a cycle, so that rates rose to their peak as inflationary pressures finally were controlled and the country fell into a recession. It just happened that in that type of cycle, rates were highest when the cycle was near its lowest. This hasn’t been the case in 40 years (Figure 1).

In the late 1980s, construction declined. Mortgage rates were flat or falling. In the late 1990s, mortgage rates bumped up a smidge, and construction flattened but basically had the most benign down cycle on record. In the late 2000s, construction shit its pants while mortgages remained below any pre-2000 level and then declined and stayed at unprecedented lows while construction did too. Then came Covid. For that, we need to look a little closer.

Did low rates cause a housing boom, then rising rates caused a housing decline? Let’s look at Figure 2. First, since they are hard to miss in the figure, let’s look at three points in time. Late 2019, fall 2021, and summer 2023. At all three points, home sales were at about 700,000 units (annualized). Wildly different mortgage rates at those three points. You could add in early 2018 as a time with home sales near 700,000 and rates around 4.5%.

Let’s look specifically at the activity in 2020 and 2021. There was a massive spike in home sales from April to July 2020 while mortgage rates declined slightly from 3.3% to 3.0%. Then sales quickly declined back to where they started while mortgage rates spent most of the next year under 3%.

If you were looking at these two measures and you didn’t begin with a very strong intuition that mortgage rates must be important, to a first approximation, I’m not sure you would see much of a relationship here.

If you squint hard enough, you could probably come up with a pretty solid thesis that briefly in 2022, there was a temporary dip of about 100,000 annualized sales down to around 600,000 units. That was related to financing frictions, the high cancellation rate of new home orders that became untenable for buyers that didn’t have their mortgage rate frozen, etc.

Before that, there was that little spike in sales in late 2021 when mortgage rates first started rising, which dropped back down near a rate of 700,000 units by March. The Fed Funds target rates was still zero in March 2022. The Fed didn’t push mortgage rates higher. It chased them higher. Good. Great. Hail to JPow. We don’t deserve him. He may have avoided recession and a housing slump, and in the process, let mortgage rates rise.

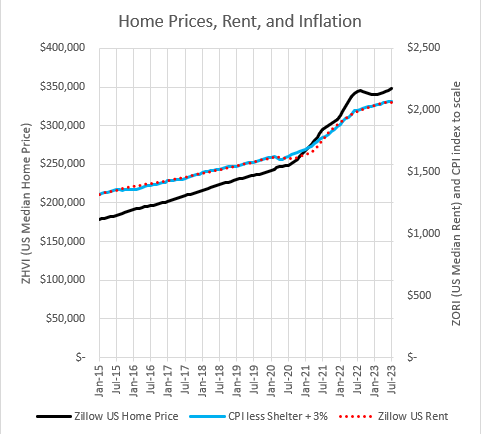

How about home prices? Figure 3 compares home prices, rents, and inflation. Here, for inflation, I have used the CPI index with Shelter removed, and I have added a 3% annual inflator so that it matches the rent inflation trend. The housing shortage has been causing rent inflation to run hotter than general inflation at this scale since before 2015. What a remarkable fit! And, as EHT readers know, home prices track excessively high rents at more than a 1:1 ratio, which is why the price trend has a higher slope here. A simple regression of price against rent over this period has a correlation of 99%. Prices don’t require any explanation, including mortgage rates, once you consider the effect of rents. Rents are rising by 3% a year because of our housing shortage, then they popped up another 10% or so exactly in line with the pop in broader inflation in 2021 and 2022, and prices reacted basically as they have been in city after city, year after year, regardless of mortgage rates.

From 2018 to 2020, there was a bit of a cyclical price decline, and then there was a cyclical recovery that peaked in mid-2022. The peak in prices, I will note, coincided with the bottom in sales. You can see the little blip there in Figure 3. Mortgages were up above 5% by the time that little cyclical bump peaked. Nothing a lag variable can’t fix - a useful kludge if you need to confirm the importance of rates. If you draw a straight line from January 2022 to July 2023, the difference between that and the price line peaks at about 6% in July 2022, if you would like to attribute all of that to a lagged effect of low mortgage rates in 2020 and 2021. It dissipated by the beginning of 2023.

There is, to an astonishing degree, little for mortgage rates to say here. On the theorist end, discount rates are not empirically debatable. That is finance. And, the notion that mortgage rates would be the discount rate applicable to home values is just too obvious to question. When I look back at very old blog posts in my previous life before I became an accidental housing analyst, that’s what I assumed. I had to be empirically dissuaded of it.

For some time, I have harbored a working theory that diversified equities have a relatively stable discount rate and that changes in aggregate stock market values mostly reflect earnings and growth expectations. I have come to have a similar reaction to home values. The discount rate is higher than the rate on mortgages and is relatively stable over time. Changing home values mostly reflect rent and growth expectations. The stock market is volatile because in all of the contexts we have managed to create economically, earnings and expectations are volatile. Home prices used to be stable because they mostly reflected the cost of construction. But, since we are decades into a housing shortage where scarcity drives rents rather than cost, rents, rent expectations, and prices have become volatile. Blaming it on “financialization” and other distractions has only served to worsen the problem.

On the practitioner side, when rates rise, certainly trading activity declines, foot traffic suffers, actual real life customers have tense meetings with sales people about how to get this thing financed, buyers downsize, etc. In fact, read generously, there really isn’t anything significantly wrong with Ara’s statement above. It’s just that he is saying it in a financial world that’s like that scene from Being John Malkovich, where all the Malkoviches are walking around saying “Malkovich. Malkovich. Malkovich.” Everyone is saying “rates, rates, rates” and as a macro-level factor in the present value of homebuilder stocks, it just doesn’t deserve that much focus.

And, that is why dummies like you and me can saunter up to the homebuilder table and keep drawing blackjacks. No lack of empirical evidence will deter investors from overestimating the effect of mortgage rates. That’s before we even get into the question of what the Fed has to do with it. The builders can manage their balance sheet for reality, but even if they don’t think mortgage rates are that important, they probably couldn’t say it without losing credibility. A good CEO says, “Our team outperformed in a terrible interest rate environment.” It’s basically true, and everyone is happy. But, it’s just one more brick in the wall of the conventional overestimation of mortgage rates that is currently temporarily holding builder share prices down.

A caveat: Mortgage rates and home size

On this topic, in an article by Alena Botros in Fortune Magazine, Zonda’s chief economist, Ali Wolf, mentions a trend of smaller new home sizes. It begins:

Let’s go back a few years, to the height of the pandemic. People were mostly working from home, mortgage rates were at historic lows, and that fueled housing demand, which pushed home prices up. But now, mortgage rates are hitting two decade highs and home prices are still high, too. This all to say that housing affordability has deteriorated, and it’s actually worse now than at the height of the housing bubble. And, it shows in more ways than one—but in this case, homes are shrinking.

“Nationally, what we’re finding is home sizes are down 10%,” Zonda’s chief economist, Ali Wolf, told Fortune.

She goes on to mention other factors that have driven up home prices and caused buyers to size down. Yet, as is typical, the article leads with mortgage rates.

That 10% figure is from a baseline of August 2018. The average 30 year mortgage rate was 4.6%, near its cyclical peak. And Wolf mentions that the trend was already in place before the Covid pandemic.

Figure 4 shows average new home size estimated by the Census Bureau and the average rate on 30 year mortgages over time (inverted to highlight the negative correlation). According to this data, average new home size has been declining for several years.

I was all ready to jump on this and add it to my examples of rate derangement syndrome. As with other claims, the recent coincidence between declining home size and rising rates seems a bit spurious if home size has been declining since 2015. But, playing around with the numbers for these measures, prices, incomes, etc. It looks like there is meaningful negative correlation between mortgage rates and average new home size. It’s not nearly as strong as the relationship between inflation, rent, and home prices in Figure 3, but it’s not nothing.

And, I think this gets at the issue. Clearly there are buyers who are credit constrained in various ways, and we can observe their buying decisions being affected by changing rates. Clearly trading activity declines when rates spike. Clearly some buyers trade down to make the financing work. But, for instance, on this issue of home size, to the extent that buyers are changing the homes they are buying because of changing rates, the prices on the homes themselves are staying firm. If a buyer was considering a $400,000, 2,500 square foot home, but after rates rise, they settle on a $370,000, 2,300 square foot home, the number of homes sold stays the same. The builder’s profit margin may stay the same. The prices on each home might stay the same. All else equal, revenues might be a little lower. But, in general, these changes will be relatively slight in aggregate estimates of home prices and construction activity.

Mortgage rates change buyer activity where we expect it to, but a lot of those changes don’t amount to nearly as much as they seem like they might at first blush. These subtle more marginal effects on the market seem to confirm the more overstated estimates of mortgage rates on construction and home prices. Investors won’t be dissuaded, and so you can count on this trading advantage to stick around.

I’ve probably mentioned it before. If everyone else was trading based on whether Mercury is in retrograde, you can earn profits by simply ignoring Mercury when you trade.

I’ll save the specific discussion related to Hovnanian’s results for paid subscribers in a separate post.

I'm willing to bet that the relative decline in home sizes correlates with the uptick in multifamily starts because condo units will range in size from 500 to 1500 s.f.--which makes me nervous about slowdowns in that area that's indicated by the AIA billings index. I'm hoping this is offset by continuing victories on the YIMBY front which lead to more variety in housing types like ADU's. The detached, single family starter home that ranged in size from 1000 to 1600 s.f. seems to have died out in the 1970's.