Note on Monetary Policy and Jackson Hole

JPow fascinates me. He has been epically good as Fed chair. But his commentary is loyal to all the broken conventional models that have made monetary policy so damaging this century.

Does he realize what’s wrong with the conventional approach, but he says the words he needs to say in order to guide the ship of fools?

Or does he work from within the bad models, but overcomes it with a strong intuition about proper decision-making in real time?

I find myself frequently put off by his commentary but quite pleased by his decision-making. Even when I disagree with the policy decisions in real time, I have generally found that the decisions I thought were errors weren’t so bad, in practice. (For instance, I would have hiked rates more slowly and stopped earlier, but so far the additional hikes have not been unavoidably recessionary.)

One general problem with the conventional view of Fed policy is what I would call the Wizard of Oz problem. Although, where the Wizard would say, “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.” the Fed says, “Why Yes! We did give you that heart, and a brain, and we’ll get you back to Kansas, too. But forgive us, it is very difficult work, what we do here behind this curtain, and if you don’t get back to Kansas, it will be due to some unforeseen trouble out of our control.”

Or, for readers who share my advanced age, the Pet Rock might be the better analogy, which came with training instructions such as “To teach your Pet Rock to FETCH, throw a stick or a ball as far as you can. Next, throw your Pet Rock as far as you can. Rarely, if ever, will your Pet Rock return with the object, but that's the way it goes.”

Powell spoke today at Jackson Hole. The speech ended with the current conventional approach to inflation:

Based on this assessment, we will proceed carefully as we decide whether to tighten further or, instead, to hold the policy rate constant and await further data. Restoring price stability is essential to achieving both sides of our dual mandate. We will need price stability to achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. We will keep at it until the job is done.

Notice how he only sees two possible near-term outcomes: hiking or pausing. I think inflation trends will call for rate cuts soon, and I expect that when that happens, Powell will shift. He has made the right calls so far. Does he know this already?

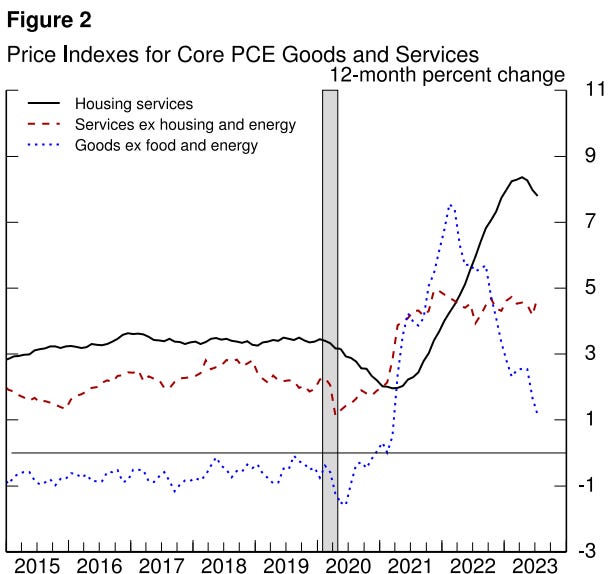

I like how he separates out housing, other services, and goods in his assessment of inflation trends. And, he continues to point out that the housing measure lags and is likely to decline significantly, so his focus is on the other two categories. His transcript includes this helpful chart.

Goods inflation still appears to be trending down, but services inflation has been flat at just under 5% since early 2021. So, the concern is that inflation is settling in at a run-rate that is still above the 2% target.

This chart actually gets at one of my main complaints about monetary policy over the past 25 years, which is that our housing supply problem creates “inflation” that is unrelated to monetary policy, or even to production. It is mostly an annual increase in the income redistribution to land rents that comes from our urban land regulation disease. It’s sort of like categorizing a tax hike as inflation.

And, you can see in his chart that in the years leading up to the pandemic, housing inflation was perennially high.

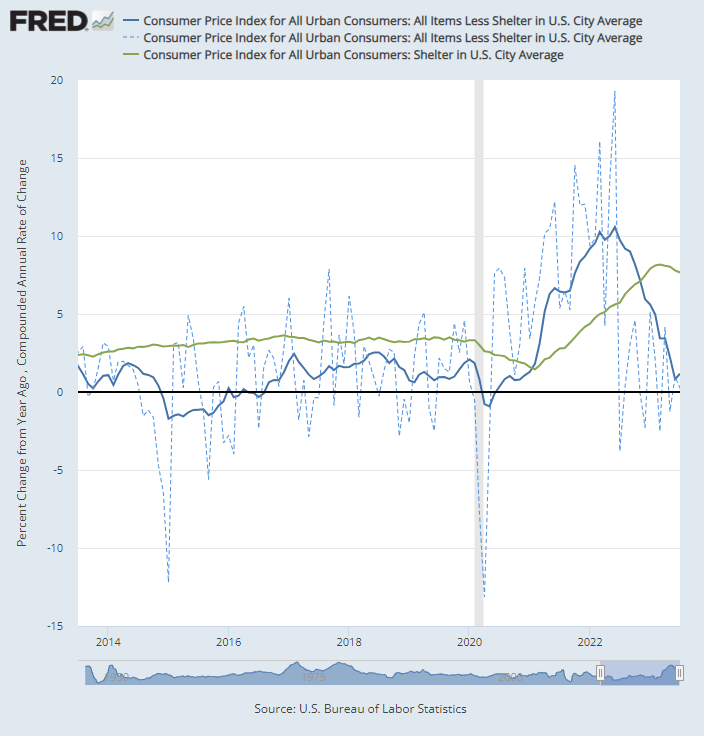

Here is a figure using CPI inflation, where I have simply divided it between shelter and non-shelter inflation. (I have included the dashed line showing month-to-month changes as a reminder that the year-over-year changes themselves are misleading in the current environment. Inflation hasn’t been slowly declining to the 2% target for a year. It has been at the 2% target for a year, and it took that long to show up in the year-over-year measures.)

As measured by the CPI, inflation now is at 3.3%. That is a combination of 7.7% shelter inflation and 1.2% everything else. The housing measure is a red herring. We are already below target. Notice also, how things were going before the pandemic. Every year, shelter inflation (which is mostly rent, plus other odds and ends like furniture, lodging, etc.) was persistently above 3% and everything else ranged between a high of around 2% and a low that was negative.

From January 2013 to January 2020, CPI inflation averaged 1.6% annually. That was a combination of 3.2% shelter inflation and 0.8% everything else. And, let’s not forget that when Covid struck, the Fed was already 7 months into a reversing their rate hikes because conditions were marginally recessionary.

So, looking back at Powell’s chart, the non-housing services and goods trends, pre-pandemic, were more than 1% too low. So, even by the measures in the PCE chart, we are back to neutral if the Fed wants to manage the economy for 2% inflation before factoring in our tax to the real estate trolls under the bridges of our major cities. We shouldn’t be aiming for pre-pandemic trends.

Specifically, on housing, Powell said:

In the highly interest-sensitive housing sector, the effects of monetary policy became apparent soon after liftoff. Mortgage rates doubled over the course of 2022, causing housing starts and sales to fall and house price growth to plummet… Going forward, if market rent growth settles near pre-pandemic levels, housing services inflation should decline toward its pre-pandemic level as well.

And, here, we’re at the Wizard of Oz problem. Mortgage rates didn’t rise as a direct result of Fed tightening. The Fed followed mortgage rates up. Ask yourself, where would mortgage rates be today if the Fed had insisted on keeping the target rate near 0%? Presumably, in order to maintain that rate, the Fed would have had to flood the economy with cash, buying up Treasuries. Inflation would have been set loose, and mortgage rates would be higher.

Of course, they would never do that. This is the problem with Fed analysis. In an effort to keep stability, they never stray far enough from the neutral rate to prove that they don’t have control. (Well, of course, they did once, when they created the 2008 financial crisis, trying to push the target rate too high in September 2008, and would have had to suck up every dollar in existence trying to do it. But, that lesson has, to my chagrin, not been widely learned. And, if they tried to set the target rate too high today by sucking up all the cash in the economy, mortgage rates would drop, just like they did then.)

There is a simple heuristic we can use here. While it is frustrating to see policymakers ignore this heuristic, it is nice that there are enough traders who ignore it to provide embarrassingly easy trading opportunities whenever interest rate fears push homebuilder share prices down temporarily, until they all report gangbuster earnings the following quarter.

In the final chart here, I have noted 2 sets of trends for three measures: the Fed Funds Rate, the market rate on 30 year mortgages, and the trend in completions of new homes.

Since the late 1980s, there have been two cycles where the target rate was hiked, mortgage rates were flat, and housing construction declined. There have been two other cycles where the target rate was hiked, mortgage rates were also rising, and housing construction remained stable.

In the bad outcomes, the Fed was raising the target too much. Mortgage rates move, for the most part, according to market conditions, not Fed policy decisions. When mortgage rates have not followed the Fed target rate higher, the Fed has mischaracterized those low rates as some sort of stimulus, taking exactly the wrong conclusion from it. When mortgage rates aren’t rising, that means that the neutral rate isn’t rising, and so Fed hikes are a true tightening of monetary policy.

By the way, Covid interrupted things in 2020, but you can see in the chart that the Fed was doing it again. They had hiked the target rate, but mortgage rates remained level. That is because economic conditions weren’t good enough to justify rate hikes. Powell seems to have good instincts, though, and he reversed course before it became fully recessionary. We will never know what would have happened if Covid hadn’t caused a shift in the economy and monetary policy in 2020. Maybe he would have pulled out of it before housing broke down, and it would have looked somewhat like 2000.

In the 2000 episode and the current episode, mortgage rates were leading the target rate higher. (In 2000, the rate hikes were relatively small, so there isn’t much to go on in terms of trend shifts, until the Fed pushed too far and rates declined, but both up and down the shift in mortgage rates led the shift in the target rate.) The same thing happened in 2022. As I have argued, mortgage rates increased because the Fed held off on rate hikes, and we owe JPow more than he’ll ever be credited for for having the instincts to do it. He broke us out of our monetary funk, and it would be a shame if he believes the words he spoke today at Jackson Hole and reverses it.

In the meantime, if you think housing’s biggest threat is rising mortgage rates, I have to tell you, I think you’re going about everything all wrong. Please short some homebuilders, if you must, but refrain from accepting a position at the Fed, please. Thank you. And thank you again when you cover those shorts.

And, say a prayer that the guest speakers at this year’s Jackson Hole conference are better than they were in 2007.

This chart actually gets at one of my main complaints about monetary policy over the past 25 years, which is that our housing supply problem creates “inflation” that is unrelated to monetary policy, or even to production. It is mostly an annual increase in the income redistribution to land rents that comes from our urban land regulation disease. It’s sort of like categorizing a tax hike as inflation.----KE

I thought I was all alone, wandering in the foggy wilderness, in gathering gloom.

Suddenly, a light! KE with a lantern!

I did not watch the GOP debates. But I gather from headlines etc that housing costs were not on the agenda.

To me that illustrates the yawning abyss between what is Washington and media, and ordinary people.

Also puzzling. Surely, even from a cynical aspect, housing is an issue that could be politically exploited, false promises made, blame assigned.

But nothing. Washington is not the capital of America. It is something else.

No wonder voters vote for oddballs.

Maybe off topic, Kevin, but do you have any comments on the Chinese real estate market and the ongoing economic situation there? I know your research is mostly U.S. focused but it can be informative to review other countries. If I understand things correctly in China they actually might have a surplus of housing, but speculative zeal has created unsustainably high prices---in other words, it's a real bubble that contrasts with the false surplus the Fed was worried about in 2005-2006.