Sorry I’m a few days late on this.

Inflation continues to be over. This is such old news that even trailing twelve month measures capture it.

My Pre-registered Inflation Standard

Back in July 2021, I wrote in the National Review that:

Turning back to 2021, as economic activity normalizes, inflation in many areas — such as, say, used cars — may prove to be temporary. But rent inflation appears to be headed back above 3 percent, where it had been before the pandemic.

If rent inflation begins to drive the broader price indexes higher while other prices moderate, that is good news. It allows the Fed to encourage more building, which will help moderate rent inflation and create quality construction jobs. This is what the Fed could have done when housing construction declined in 2006 and 2007. At that time, though, the depth of our housing supply problem wasn’t well understood. There is no reason to make the same mistake again. What we need, once and for all, is a monetary policy that is stimulative enough to break out of our housing slump.

We have arrived at that time. It didn’t play out exactly as I expected. The transitory inflation was higher and longer than I expected it to be. And, since it took so long to get to this point, even rent inflation might decelerate in the coming months. Yet, there remains the ever present danger of backward looking inflation sentiment which threatens to push the Fed into pro-cyclical policy decisions.

There are several reasons why rent, or more broadly shelter, inflation is problematic. One way to think of it is that if demand was driving rent inflation (from any of the usual suspects - low interest rates, generous mortgage programs, tax incentives, speculation, FOMO, Community Reinvestment Act <Does anyone ever claim that one any more?>) then real spending on housing would be rising. It would be related to production. And it would be relevant. Certainly, there are still building cycles, and so there are times where that dynamic is more relevant than other times. But those cyclical fluctuations are happening within a broader context where production is perennially lacking. So, rent inflation represents an increase in land rents. It has little to do with production. It is simply an increase in a transfer based on limited access to an endowment - paying the troll under the bridge. I think the easiest way to deal with this is to just leave the shelter component out of the inflation index.

This problem is deeply embedded in the academic and public discourse about monetary policy. The wealth transfer driven by land rents is routinely mistaken as overconsumption driven by credit or subsidy, and so deprivation is routinely mistaken as excess. It is a category error in empirical clothing.

Inflation is Over, Still

Figure 1 shows monthly and 3 month rolling inflation trends, with or without shelter.

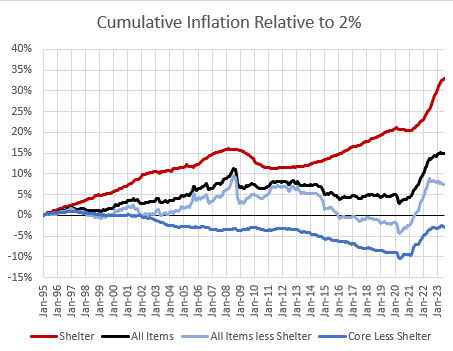

Figure 2 shows the long term trend of each measure, relative to a 2% trend. All of the inflation over 2% over the last 3 decades has been from shelter and from a bout of energy inflation in the 2000s. The recent spike in inflation was relatively uniform in all categories, which strongly suggests that it was a monetary phenomenon. But, for any period longer than a few years, the spike was a continuation away from the 2% trendline for shelter, a fluctuation around the 2% trend line for energy, and only a partial recovery to a 2% trend line for other categories. We are now more than a year in to all the categories except shelter settling back into something close to a 2% trend.

So, at this point, with little risk of unmoored expectations or forward inflation away from the trend, I am disappointed by the amount of consternation about the short-lived spike.

The Mystery of Transitory Inflation

There is an ongoing debate about whether inflation was truly transitory. Wouldn’t transitory inflation have reversed rather than settling back into trend at a higher level?

The decline in inflation trends and inflation expectations did happen before there were substantial rate hikes, suggesting that it wasn’t related to monetary policy. But it has coincided with the growth of various monetary aggregates which also leveled out at a higher level, as shown in Figure 3.

But, this just creates more mysteries. In the period between the 2008 crisis and Covid, the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet was relatively weak, only slightly pushing up inflation with large expansions in the money supply and Fed asset holdings. The reversal of monetary growth coincided with the sudden return to normal of inflation after June 2022. So, even though the decline in inflation wasn’t triggered by rate hikes, maybe it was triggered by the levelling out in Fed assets and the money supply.

Does that mean that a Fed Funds target rate near zero (and highly negative in real terms) was compatible with a return to 2% inflation? And, if so, why hasn’t the increase to more than 5% (and a much larger increase in real terms) had more of a bite on forward inflation?

The yield curve doesn’t help clarify much. Figure 4 compares the yield curve using the forward 3 month Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) at 5 different points. (The interest rate is 100 minus the number on the y-axis.) Inflation was back to normal by July 2022, on a month-to-month basis. There has not been any new information since then to induce a higher target rate. And, as the Fed raised the target rate anyway, the yield curve flattened. This is generally a recessionary indicator. Yet, the long end of the curve rose, which may be an indication of future growth, and those expectations are plausible since there are several sectors that are still recovering from Covid-era supply hiccups. As with the few years preceding the Covid shock, the Fed seems to be perched on the edge of a recessionary posture, but just on the happy side of it.

Rates have been relatively stable since the autumn of 2022, and whenever the curve becomes worryingly flat, it bounces back. As the current target rate has continued to rise, the expectations for rates from 2024 to 2028 predict a relatively steep return back down below 4%.

So, I think one reason the additional hikes from 3% to 5%+ haven’t been particularly recessionary is because they are seen as temporary. Bank lending for residential mortgages and construction loans have continued to rise throughout the period of rising rates, only levelling off since May.

A Theory of Potential Growth

As Figure 5 shows, if we use a 5% nominal GDP growth trend line from 2016, nominal GDP has sidled quite nicely right back up to trend. NGDP was recently updated through the second quarter 2023, coming in at slightly below 5%. That trend line accepts a permanent 14% nominal shock after 2007, but a return to the pre-2008 growth rate (the yellow line compared to the orange line).

I think we could describe what happened as a permanent shock due mainly to the one-time re-calibration of mortgage lending standards. It led to a major employment shock in construction and also a sharp decline in real consumption and production of shelter. Eventually, by the mid-2010s, the new normal was basically in place. Much of the shock will play out as an increase in inequitable housing consumption. For the better part of a century, reasonably generous lending standards had encouraged ample housing construction, which kept rents low. Increasingly in the late 20th century, urban land use regulations created localized rent inflation which created inequitable housing inflation. American families segregated regionally to deal with that. Americans with lower incomes lowered expenditures by moving to less regulated cities.

After 2008, that 2nd best alternative was largely shut down by overzealous mortgage regulation, so that Americans with lower incomes faced higher costs in all cities. In 2030, compared to 1980, the difference between what rich and poor Americans pay for housing will be narrower, but the difference in how good their housing is will be greater. As with GDP, this decline in housing production is basically a one-time shock, which happened after 2008.

That shock is unsustainable. By 2017, residential investment was recovering back toward a rate that would normally be considered non-recessionary. The collapse of entry-level single-family owner-occupied home construction was replaced with a moderate boom in multi-family construction and increasingly with single-family build-to-rent.

The way I look at this is that if those other categories of construction can continue to grow, then the housing shock will truly be a one-time event, and NGDP can now return to a 5% growth rate with a normal amount of residential investment.

If those categories can’t grow - and there is a real danger that they can’t because of public resistance to urban infill growth and motivated ignorance about the effect of private equity in housing affordability - then, it is possible that real production will settle back down to a rate more compatible with 4% NGDP growth. But, in that case, we will return to the pattern in Figure 2 where shelter inflation continues to rise. So, the 1% annual increase in the transfer of land rents will push measured NGDP growth up to 5%.

In other words, roughly speaking, I think it is reasonable to expect 3% real growth and 2% inflation. But if we continue to unhouse ourselves, then it will be 2% real growth and 3% inflation, which will be a combination of 2% non-shelter inflation plus an extra 1% of shelter inflation.

If the residential inequity shock is continuous, I think we are potentially in for some politically devastating times. Real residential investment has to recover. The nominal economy should be managed for that recovery.

For now, the trajectory looks ok. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tool is forecasting real GDP growth in the 3rd quarter of 2023 above 4%. There is some low hanging fruit in automobiles and residential investment for moderate deflation as the last of the transitory inflation factors are healed. It seems plausible, even probable, that a year from now we really will be able to look back and say that much of the excess inflation reversed. Maybe we will have a year of 4%+ real growth with negligible inflation. The foundation for that is here. There is a lot of room for increased auto production and housing construction, and both sectors appear to be moving in that direction. Maybe inflation was transitory - in that much of the temporary inflation is reversed - and the timeline was just such a jumbled mess that it will take a couple of years of hindsight to realize what has happened.

I think, given all of this, the homebuilders will continue to be a key sector to watch. Construction lead times have been improving, and demand has continued to be strong enough to take all the supply they can produce. If that can continue, maybe the happy scenario can play out. (Well, the happy scenario would be a reversal of the post-2008 housing shock, but at least we can hope to avoid the scary scenario.)

"In other words, roughly speaking, I think it is reasonable to expect 3% real growth and 2% inflation. But if we continue to unhouse ourselves, then it will be 2% real growth and 3% inflation, which will be a combination of 2% non-shelter inflation plus an extra 1% of shelter inflation."--KE

My back of the envelope, and use the setting sun as a direction-finder ways suggest to me the above is true.

It is also a topic of global interest.

Recently, there seems to be a lot of chatter from Canadians they cannot afford to live there anymore, with housing at the core of the commentary. One Toronto resident lived in Eastern Europe for a half-year, returned home and said they actually have higher living standards there after pondering housing costs. An anecdote, sure.

My quick study is that residents of Sapporo, Japan (average $400 a month in rent) have higher living standards than people in Los Angeles (five-six times that).

Seoul, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Australia, UK...even Thailand has seen escalating house prices.

I salute KE. The macroeconomics profession need to wrestle with real world, huge structural impediments that can make mincemeat of theories.

Unless a modern nation has an aggressive priority approach to building housing stock (orimarily through unzoning property) it seems housing-poverty results.

Japan being an exception, but then they are an exception to everything. Well, they do have light zoning, or so everybody says. Also a declining population.

Add on from NY Fed:

Multivariate Core Trend Inflation

June 2023 Update

Multivariate Core Trend (MCT) inflation decreased to 2.9 percent in June from 3.2 percent (a downward revision) in May. The 68 percent probability band is (2.5,3.4).

Housing accounted for 0.44 percentage point (ppt) of the MCT estimate, while services ex-housing accounted for 0.40 ppt. Core goods had a lower contribution of 0.22 ppt.

Persistence in both housing and services ex-housing inflation was dominated by the sector-specific component of the trend.

Latest Release: 2:00 p.m. ET August 1, 2023

Multivariate Core Trend of PCE Inflation