A Review of Gjerstad and Smith, Part 2

In Part 1 of my review of the April 2009 Wall Street Journal op-ed (wayback machine link) by Steven Gjerstad and Vernon Smith, I argued that the approach they took to the American housing market magnified the importance of “bubble” mechanisms. By the 2000s, home values far exceeded the range that had previously reflected normal boom and bust financial fluctuations. Gjerstad and Smith amplified their estimate of what “bubble” mechanisms could explain, rather than expand the scope of their inquiry to other factors, such as supply constraints.

In this post, I will argue that this op-ed followed a path common among those with a bubble focus. Interest rates are too low, prices are too high, and production is overstimulated. Or they are not. But, rates are never too high, prices too low, or stimulus called for. Observations are highly selective. They reflect what Tyler Cowen calls “mood affiliation”.

John Taylor

First, I will take a brief detour from the Gjerstad and Smith op-ed. Their analysis is not particularly unusual in this regard. In a key August 2007 speech to the Fed, John Taylor demonstrated the selective observation of both price and quantity variables that is common in bubble-focused analysis. I described these biases in “Building from the Ground Up”.

From the first quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2009, the Fed’s estimate of the total number of homes that would be built from 2006 through 2011 declined by six million units. Building rates would continue at historically low levels for years afterward. Conventional wisdom accepted this as a necessary reaction to having built too many units in the boom. It is strange that it did so. There is absolutely no way to add up housing construction activity before 2006 and find extra units anywhere close to six million. That size of a decline is actually strong evidence that the problem was an extreme demand shock—a lack of funding for buying and building homes after 2006. That is the only remotely reasonable explanation for it. A contraction leading to a decline in the future rate of building of one or two million units could have been plausibly explained as a correction to overbuilding. The contraction in the Fed’s forecast of housing starts was already that large by mid-2007 when prices started to collapse. I have argued that there was never systematic oversupply. Certainly, by the time home prices were collapsing, there was not. With each passing quarter, the expected construction implied by the Fed’s continually declining forecasts moved down by about another half million units. Each quarter should have been further evidence that builders were being hit by a demand shock—a lack of money and credit required to build needed homes—rather than a supply correction, but it was interpreted as the opposite. The Fed had created a severe demand shock and they never were able to awaken from the trance they had stumbled into. Really, the trance everyone had stumbled into.

It is common for actual outcomes to be more volatile than forecasts and for forecasts to reflect recent trends. The point is that the Fed is a special sort of institution. It has some control over how many dollars Americans spend by creating inflation or deflation of those dollars. When the price of consumer goods declines, the Fed forecasts a reversal of that decline because it intends to assert control over those prices. When the price and construction of homes continued their long decline, the Fed forecast the continuation of that decline because it did not assert control over home prices and construction activity.

Most monetary policy experts would agree that this is entirely appropriate. The Fed controls consumer prices, not asset prices. That is all well and good as a principle. But did the Fed or its critics really follow that principle?

One of the common measures researchers use to estimate appropriate monetary policy is the Taylor Rule. It is a guideline for targeting short-term interest rates in a way that is intended to produce stable, low inflation and low unemployment. John Taylor, who that rule is named after, has been a critic of Fed policy in the years before the crisis. In his book, Getting Off Track, about the causes of the financial crisis, chapter 1 begins:

“The classic explanation of financial crises, going back hundreds of years, is that they are caused by excesses—frequently monetary excesses—that lead to a boom and an inevitable bust. In the recent crisis we had a housing boom and bust, which in turn led to financial turmoil in the United States and other countries. I begin by showing that monetary excesses were the main cause of that boom and the resulting bust.”

In that chapter, he claims that the Fed should have raised interest rates earlier, and he argues that those higher rates would have led to lower home prices and fewer housing starts. He estimated that Fed stimulus had led to an oversupply of about one million homes. Later, Taylor writes that “the housing boom was the most noticeable effect of the monetary excesses.” Clearly, it wasn’t ’70s-style consumer inflation that led to his criticisms. It was home prices. He was critical of the Fed because he blamed them for high asset prices, and he concluded that high prices must have led to overbuilding.

Critics and commentators wonder how the Fed could have been so surprised by the collapse. Yet few argue that the Fed should have acted more forcefully to prevent the collapse. Boosting asset markets would’ve been inappropriate. Instead, they usually argue that the Fed should have specifically aimed to lower asset prices a few years earlier than they did. In the end, the critics aren’t arguing that there is a principle against the Fed targeting asset prices. Critics commonly say that the Fed should have reacted against high home prices before 2006. They are arguing for a one-way principle: The Fed should explicitly push asset prices down when they are rising but should not support asset prices when they are declining, because that would be a bailout.

What sort of outcome should we expect from a system where the central bank is only supposed to try to directly affect asset prices in order to bring them down but never to stabilize them or bring them up? Eventually, inevitably, it will lead to the very outcome we got. Either ignoring asset prices or trying to control them both up and down would be better than this monetary masochism.

So, we have various asymmetries here.

Consumer prices. Low and stable inflation is the target. There is a consensus asymmetry here. Nobody calls for a deep deflationary shock to make up for past inflation. Inflation was still above 3% when Volcker’s term as Fed chair ended in 1987.

Asset prices. Home prices are really the primary source of complaints about over-stimulative monetary policy in the 2000s, since consumer inflation reliably followed a downtrend to the Fed’s 2% stated target after the 1980s. But, Fed critics tend to be selective about focusing on asset prices. Here, the asymmetry is reversed from the consensus about consumer prices. Fed critics call for austerity when prices seem high, but then they support a subsequent deflationary countertrend.

Supply. As described in the excerpt above, I think the issue here is mainly one of selective observer’s bias. As I have written about before, there was little effort put into quantifying how much oversupply of housing there was before 2008. The idea that there was, or even could have been, an oversupply of homes, is somewhere between suspect and ludicrous. Since bubble-focused analysis is based on an idea that low interest rates or other forms of subsidy or stimulus are responsible for higher home prices, oversupply is mostly a presumption. There is always some evidence that can be cited to confirm the presumption. And when production collapses, it ceases to be a topic of interest. The first arrow (“2007 Leamer presentation”) in Figure 1 points to the Jackson Hole retreat where John Taylor complained to Fed members that they had overstimulated the production of a million too many homes. The measure is the quarterly number of housing starts, expressed as an annualized percentage of the existing stock of homes.

Prices and Object Permanence

So, back to Gjerstad and Smith in April 2009. They complain that the Fed didn’t tighten monetary policy in response to rising home prices, an explicit call for some sort of asset price target regime. The way they try to bring asset values into the Fed reaction function is by replacing owner-equivalent rent in the CPI with homeowner costs.*

In 2004 alone, the price-rent ratio increased 12.3%. Inflation for that year was underestimated by 2.9 percentage points (since "owners' equivalent rent" is about 23% of the CPI). If home-ownership costs were included in the CPI, inflation would have been 6.2% instead of 3.3%.

With nominal interest rates around 6% and inflation around 6%, the real interest rate was near zero, so household borrowing took off.

Then they spent many paragraphs discussing how losses, specifically in housing, have a devastating effect on the economy. So, deep losses in the stock market in 2001 were much less economically disruptive than losses in the housing market in 2008. Yet, in all of their extensive discussion of that problem, they neglected to revisit the inflation index that they had introduced in the op-ed.

Figure 2 highlights the effect of their proposed adjustment to the CPI. In December 2004, it would have added 2.9 percentage points to reported inflation. At the time their op-ed was published, with the CPI was reporting 0.6% deflation over the previous 12 months, their adjustment would have lowered the inflation estimate by an additional 3.3%.

If home prices really, truly, should be part of a consumer price index (They shouldn’t be.) then home prices should be managed like Volcker managed inflation in the 1980s. Price inflation should have gradually slowed down. But, in the bubble-focused framework, assets become overpriced and then have to decline to return to normal.

Gjerstad and Smith need to decide whether home prices should be managed like consumer prices or not managed like asset prices. Instead, their model of the economy requires having it both ways, in the worst possible way, so that, without acknowledging it, they are acquiescing to intensive nominal destabilization.

If the Fed should have been raising rates higher in 2004 because of housing inflation, then, by Gjerstad and Smith’s standard, it should have been stimulating by the end of 2006, and by April 2009, their entire op-ed should have been a plea for massive, urgent stimulus.

They wrote another op-ed (wayback link) in the Wall Street Journal in September 2010.

Our study of all the postwar recessions and the Great Depression leads to the following empirical proposition: If there is no recovery in housing expenditures, confirmed by a recovery in consumer durable goods expenditures, then there is no economic recovery.

In the Great Depression and in every recession since, recovery of residential construction has preceded recovery in every other sector, and its recovery has been far larger in percentage terms than the recovery in any other major sector.

Applied to the Great Recession, it appears that those who see signs of a recovery may be grasping at straws. What one should hope is that this time it is different from every one of the past 14 U.S. downturns, but those who believe this have the weight of past experience against them…

No currently debated policy will likely change this situation, as the market is saturated with foreclosed houses and homeowners suffer from $771 billion in negative equity. This fact needs to be confronted: We are almost surely in for a long slog.

In the 12 months leading up to September 2010, the CPI, adjusted with house prices as they had in the April 2009 op-ed, was still a paltry 0.4%. But, there would still be no plea for stimulus. It is true that "no currently debated policy” would have changed the rotten economic situation. And that is a shame.

The bubble framework was wrong. It needed to be updated. Housing supply had been broken for years, and now it was broken everywhere (“those who see signs of a recovery may be grasping at straws”). What did the bubble model have to offer us - in September freaking 2010?!: “This fact needs to be confronted: We are almost surely in for a long slog.”

Well, I sure hope their model was right! Because if it wasn’t, what a bitter pill that is.

Supply and Picking Cherries

Gjerstad and Smith didn’t really address the supply side in the 2009 op-ed. They did address it in the September 2010 op-ed.

The onset of and decline during this recession were like previous recessions, though its course has been deeper and longer. By quarter four of 2007, sales of new homes had fallen without interruption for nine straight quarters and expenditures on new residential construction had fallen for seven quarters—strong lead time signals of the looming distress. New home sales recovered briefly in 2009 but have now declined for three quarters. Residential construction expenditures have essentially been flat for five quarters.

Notice, this confirms what I wrote above. By the time Taylor addressed the Fed in August 2007, the decline in residential construction was 2 years old. In September 2010, Gjerstad and Smith could still look back on what was now a 5 year decline, refer to the 3 year old signal, and still refer to it, in hindsight as “strong lead time signals of the looming distress”, and still refer to hopes for recovery as “grasping at straws”.

To clarify how off base this was, and to note that Gjerstad and Smith reflected conventional wisdom on this, here is what I wrote in “Build More Houses”:

Ben Bernanke wrote in his memoir: “Builders would start construction on only about 600,000 homes in 2011, compared to more than 2 million in 2005. To some extent, that drop represented the flip side of the pre-crisis boom. Too many houses had been built, and now the excess supply was being worked off.” The years 2009 and 2010 saw fewer new houses as a percentage of the existing stock of housing than any other 2-year period since at least 1965. In fact, the same can be said for the 3 years leading up to 2010, the 4 years leading up to 2010, and so on. For every period of any length of time since 1965, the period ending in 2010 is the period with the lowest number of permits and shipments as a percentage of the existing stock of homes.

Figure 3 is from that paper, and tracks residential investment over time. The top, blue line is reported gross residential investment, as a percentage of GDP. It was arguably inflated, briefly, in 2005.

Residential investment, as reported, includes brokers’ commissions on sold homes. Obviously, fees to brokers don’t add to the stock of homes. So, the orange line is residential investment in structures, which doesn’t include brokers’ commissions.

The gray line also subtracts depreciation of the existing stock of homes. So, the gray line is an estimate of the actual change in the housing capital base each year. Compare that line to the trend in the Fed Funds Rate that Gjerstad and Smith included in their op-ed. Does that gray line look like the result of 40 years of overstimulation?

Is there any article anywhere in the housing bubble literature that even addresses these trends in supply? Oversupply was simply assumed, because the bubble model infers that overstimulated demand caused prices to rise, and more supply is what you’d get from that. The lack of actual oversupply was mostly ignored. At best, you might see a reference, here or there, to the most inflated evidence of housing production, like the blue line in Figure 3, or cyclical estimates of building activity that ignore the deep, long-term secular decline that the cycle was operating on. I’m not aware of any bubble literature that takes an objective look at housing production and addresses doubts. “Well, it may look, by some measures, like housing supply has been low, but here is why it’s not as low as it seems.” Even simply doing that would make it hard to tell readers in 2010 that a long slog is all they can hope for. “Well, you might think there should be more housing construction, but if you make these non-obvious adjustments to the data, you can see that, in spite of appearances, 2 million construction workers will just have to accept long-term unemployment.” Unfortunately, nobody at the time was of a mind, nor in a position of authority, to question the anti-building mania.

By the way, one last note on the brokers’ commissions issue. If anything, increased expenditures on brokers’ commissions should reduce home values. Transactions costs are a friction in asset markets. By 2005, brokers’ commissions peaked at almost 1.5% of US GDP!

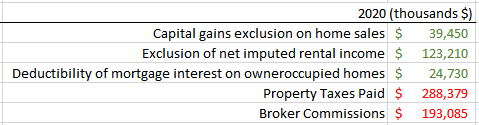

Gjerstad and Smith mentioned the importance of the change in capital gains taxation on home values leading up to the relative doubling of home prices. Here is a table comparing the scale of the estimated cost or credit of some of the largest tax categories in housing, along with total brokers’ commissions.

Conclusion

I think the issues here in part 2 are things that curious analysts with a curious audience could have picked up on in 2009 or 2010 - or in 2007. The bubble framework had a hold of us, and so 2008 and its aftermath were the victims of universal incuriosity about the most important questions of the time. The odd thing about incuriosity is how easy it is. Did it occur to anyone how odd it was for Gjerstad and Smith to apply their CPI adjustment so selectively? The best way to be unpopular in April 2009 would have been to call for stimulus, recovery, or stability in home prices, or, Heaven forfend, a loosening up of lending norms.

In part 3, I will follow up with some other points of concern which might have required 10 or 15 years of hindsight to fully appreciate.

*It isn’t clear exactly how they adjusted the CPI. In Figure 2, I simply replaced the owner-occupied rent portion of CPI with the Case-Shiller home price index.