A Review of Gjerstad and Smith, Part 1

I was reminded of two old Wall Street Journal op-eds that provide a concise collection of elements of the conventional view of 21st century housing markets. Maybe a point by point review will be edifying.

The op-eds are co-authored by Steven Gjerstad and Nobel Prize winner Vernon Smith, who also co-authored a book entitled “Rethinking Housing Bubbles”. The first op-ed was published in April 2009, titled, “From Bubble to Depression?” (wayback machine link).

At the end of the day, our explanation of complex systems is a Gish Gallop. There are inevitably large areas of uncertainty and empirical short cuts. Our conclusions’ usefulness depends on how much the uncertain parts match with reality, and their popularity depends on how much our audience agrees with the assertions and short cuts we apply to that uncertainty.

It is easy to underestimate how much of our explanation of complex phenomena is a product of which inputs receive the benefit of the doubt in the uncertain corners of our mental model.

A good example of this sort of problem is the effect of interest rates on home prices, which I go on about here frequently, and of which I have shifted away from as a an important factor creating trends in home prices. When home prices fail to ever revert back down to where they were when mortgage rates were 3%, most people will choose to backfill their mental model with all sorts of details about rate lock of homeowners, etc. (details which frequently contain some truth!) rather than lower their estimation of the effect of interest rates. There is a lot of uncertainty in our understanding of asset prices, and within that area, interest rates enjoy a very strong benefit of the doubt. So, rather than simplifying models when interest rates fail to have a powerful effect on home prices, models are patched with Ptolemaic complications.

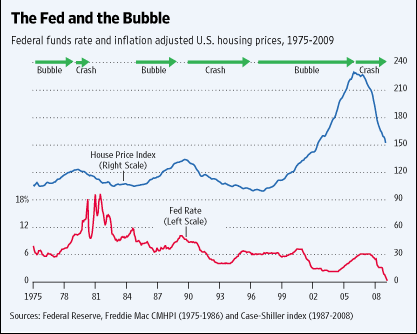

This issue is probably a good place to start, because it’s where Smith and Gjerstad start. They start with Smith’s famous experimental findings: “Even when traders in an asset market know the value of the asset, bubbles form dependably. Bubbles can arise when some agents buy not on fundamental value, but on price trend or momentum. If momentum traders have more liquidity, they can sustain a bubble longer.” Then they include this chart:

Interest Rates

Figure 2 compares a time series of the Fed’s target short term interest rate and home prices adjusted for inflation. How much importance should we ascribe to the relationship between these two measures?

There are two mismatches going on in Figure 2. One measure is a level and one is a rate. One measure is real and one is nominal.

Within the interest rate measure, itself, rates were higher in the 1970s, mostly, because inflation was higher. Isn’t part of the bubble story that when inflation is high, it creates a pro-cyclical investment cycle? Most of the decline in interest rates has been due to declining inflation. The Great Moderation is hardly a secret.

In November 2000, the Fed Funds Rate was 6.5% and unemployment was at 3.9%. By January 2002, the Fed Funds Rate was down to 1.7% and unemployment was at 5.7%. They wrote, “The 2001 recession might have ended the bubble, but the Federal Reserve decided to pursue an unusually expansionary monetary policy in order to counteract the downturn.”

What’s the counterfactual here? What Fed Funds Rate was the proper target rate in 2001? What unemployment rate would have resulted? What would have been the target Fed Funds Rate by 2003 in that counterfactual scenario?

Bubbles exist, therefore this is a bubble.

The problem here is that there is simply no room for a non-bubble story. Those green arrows at the top of Figure 2 are telling. The market is either in a bubble or not.

Demand-focused housing scholars will usually acknowledge that supply is an important element. They will note that demand factors like interest rates, speculation, etc. especially push up prices where supply is inelastic. But, as in these op-eds, its causal importance is washed away.

The Ptolemaic scholar says, “Yes, of course we are spinning on our axis, and this affects the position of bodies in the sky.” And then they add another epicycle to control for it.

The cross-sectional differences between and within cities that my model tracks and some of my Mercatus papers have highlighted can shine a bright light on the role of supply in these price trends. In national aggregates, one can assume that supply is a constant. Homes can be constructed somewhere. And, the fact that the recent excess aggregate national value of residential real estate comes entirely from the poorer neighborhoods in the cities with the most inelastic supply is cast out beyond the reach of observation. So, the epicycle accounting for supply constraints doesn’t even get a nod - here, or as far as I can tell, in their book. It’s just all bubbles or non-bubbles. The rest is in the shadows.

Degrees of freedom, behavioral explanations, and scale

Smith and Gjerstad also make a presumption common in Austrian econ circles, which is that the bottom of the market is the normal price, and any prices above that are excessive. So, they place the start of the mega-bubble in 1997, where relative prices started to rise from their nadir. That means that by 2000, home prices are well into bubble territory, and, so, they were fitting for a bubble narrative.

Why were home prices so far into bubble territory? Smith and Gjerstad point to a change in capital gains taxation in 1997. Home sellers could now claim $500,000 in untaxed capital gains. At the time, the tax rate would have been 20%. So, some fraction of a typical home’s value received a 20% tax subsidy. Back-of-the-envelope math would put the maximum effect of such a change at something south of 10% of a home’s value.

And, I think this is where behavioral explanations like bubbles get into real trouble, because where a rational model would suggest less than a 10% price boost, and actual prices have doubled, “bubble” can swoop in to save your model. Irrationality cannot be falsified, and so model risk becomes unmoored. Once a “bubble” multiplier can be applied to any variable, your model can explain everything.

Out of sample, out of scale

For decades, home values had swung 10% to either side of a cyclically neutral valuation. Sure, call the top half of those bubbles.

If all of a sudden, the price swings to double what had been the neutral value, one important thing to consider is, “Maybe something new is happening.”

But, there was plenty of fodder to support the bubble story.

“Both the Clinton and Bush administrations aggressively pursued the goal of expanding homeownership, so credit standards eroded. Lenders and the investment banks that securitized mortgages used rising home prices to justify loans to buyers with limited assets and income. Rating agencies accepted the hypothesis of ever rising home values, gave large portions of each security issue an investment-grade rating, and investors gobbled them up.”

All of that was, more or less, true, and it all added qualitative support for the multiplicative effects of “bubble” models. So, a theory that treats the history of American housing as a series of bubbles settled on the confirmation that what we had here was the mother of all bubbles.

Much of the op-ed describes the unravelling of CDO markets, falling home values, etc.

If you looked closely enough, even by April 2009, the unravelling of the bubble was not really a symmetrical reversal of its rise.

But, bubble narratives can plug holes in your model on the way down just as well as they do on the way up. So, the mother of all bubbles surely had to pop. It was something we needed to let happen or make happen. And, sure, in the chaos of unravelling, some borrowers and neighborhoods might get caught up in the volatility, even though they shouldn’t have.

So, that deep dive in the blue line in Figure 2 was inevitable, even if the details were a bit fudgy on the way down.

The Rest of the Story

I will continue the review in part 2 and part 3.

I doubt that anything I have written here would convince anyone to reconsider their priors who hasn’t already been convinced. These are big macro-level discussions with lots of room for doubt. I’m being too dismissive of models that rest on tests in countless academic papers.

But, I hope we can agree that the model the op-ed used for approaching the 2009 housing market was far from indisputable, and that there is a possibility that extreme changes in home values after the 1990s called for model doubt rather than model certainty.

In part 2, I will highlight how many of the empirical claims in the rest of the op-ed were motivated by model overconfidence or were empirically wrong - sometimes in ways that could have been clear at the time, and sometimes in ways that have been made more clear with 14 years of hindsight.

I love that line: "....the presumption...is that the bottom of the market is the normal price." Which implies that unless there's a fire sale then consumers are getting shafted by greedy businesses who are conspiring to keep prices elevated through nefarious means. If this were true then Utopia could be achieved by a deflationary economy where all prices for all goods and services eventually reached zero. Maybe we will achieve that paradise someday, but for now we have to tolerate a nominal monetary system where prices can, and should, fluctuate.

Speaking of prices, PCE continues a downward trajectory. Powell has hinted at future rate hikes but with these trends the Governors should probably do nothing for a few more months. The next few years could resemble the 1990's--which I don't think would be a bad thing for the economy. The worst thing that happened during that decade was the invention of the Internet--curse you Al Gore!