A quick note today on agglomeration economies. I have written here and there about it. There seems to be a tendency among economists to emphasize the productivity of cities as a reason for expensive housing. Like, the thing that makes our time different than previous eras is that our cities have become much more productive.

This bias has led a lot of smart people to overestimate the amount of demand for living in the Closed Access cities (NYC, LA, San Francisco/San Jose, and Boston). I think this is especially the case because a lot of those smart people live in New York and San Francisco, and it makes perfect sense to them that they are smart, that living in proximity to them makes other people productive, and their specialness is what makes housing expensive.

So, existing San Francisco bay residents blame high prices on tech workers, but their misdiagnosis of the problem is also flattering to the tech workers, leaving everyone with an inclination toward misdiagnosis. The body of economics literature on the value of cities naturally provides a foundation of legitimacy under all of that.

A previous post here about it was in response to a Scott Alexander post at AstralCodexTen where, like many smart people, he had been taken in by the notion. Scott, being especially thoughtful, appears to have corrected his position, though it took some work to get him there. I should note that it was a large plurality among his readers who were economists who convinced him supply was important, so maybe I’m being too hard on economists when I generalize.

NIMBYs frequently invoke some version of agglomeration. All change requires some compromise. All housing politics is about those changes - new residents and structures that don’t fit well with existing residents and structures. In a city with a lack of adequate housing, those compromises all tend to be richer households compromising into poorer neighborhoods and poorer households either paying more or moving away from the city.

So, ironically, tenant-activists and social justice activists in cities that lack housing frequently view new housing as the source of all displacement. Former San Francisco supervisor David Campos commonly expresses this approach. A recent tweet said:

That’s the Yimby vision isn’t it, “bring in new people.” That means push out many people who are here, many who’ve worked to make San Francisco what it is, many who are low and middle income, LGBTQ and people of color. Well, we won’t to be pushed out without fighting for our city.

The implication here is that every new home will bring in at least one more person. Growth and size are such powerful forces of value that growth itself induces an unsustainable amount of knock-on growth.

The math is implausible if you think about it. (Some YIMBYs note that this means we should build like crazy in San Francisco. We would be rich beyond our wildest imaginations if 50 million San Franciscans would cause San Francisco to have even higher incomes and higher real estate values.)

But, even though the math is implausible, even some non-NIMBYs think building more homes in the expensive cities will only make them more expensive.

Anyway, this has all been a rambling prelude to a simple chart to clarify the importance of agglomeration.

If this really was the age of agglomeration economies, what would you expect to see? The implication of the agglomeration proponents is that a handful of super-productive cities has drawn in new workers. The more they grow the more value they accumulate. They are growing and getting rich.

As I have laid it out before, Austin and Seattle can lay some claim to that description. San Francisco and San Jose have what I would call potential agglomeration economies that they have squandered.

In Figure 1, the x-axis is the average annual number of approved housing units per capita from 1994 to 2018. How much is the metro area growing? How many new homes, as Campos would imagine it, are they building to attract new hotshots and price out the locals? (Of course, outmigration of locals is negatively correlated with new home construction, and it isn’t remotely debatable. Every new home means nearly one less local moving away, not more locals moving away.)

The y-axis is the change in real per capita income from 1994 to 2018.

I am not going to get into mathematical complications here, but of the slow growing metros, some just have slow growing economies. You can see them in the bottom left - Detroit, Cleveland, etc. They didn’t build more homes because they didn’t need more homes. Among the other cities, there is a sharp trend. The incomes have gotten really high where they approve very few homes.

That is the opposite of agglomeration economies.

It happens that 1994 is about when the housing shortage started to show its signs. Rent inflation has been persistently high in national numbers since then, for instance.

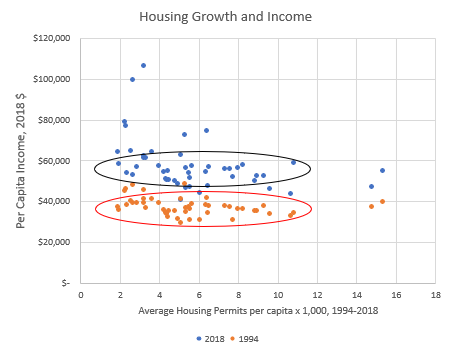

In Figure 2, using the same x-axis measure, I plotted the starting 1994 income and the ending 2018 income on the y-axis. So, Figure 1 is basically the vertical distance between the dots in Figure 2.

And, the striking thing is that even as late as 1994, incomes among all cities were not very different. The standard deviation in 1994 among these 49 metros was about 11% of the average income. By 2018, it had almost doubled to 21%. You can visually see the variance.

So almost all of the income gains came in the cities that didn’t grow. Agglomeration might be happening, but no claims should be made about agglomeration at all until a thorough and careful control for Closed Access displacement is complete. Their incomes are high because their poorest residents moved away, not because they have suddenly multiplied previous sources of urban productivity.

Really, what you can see in Figure 2 is that where labor and capital are allowed to flow in a developed economy, incomes can’t differ by more than about 10% between cities. When they do, capital and labor move until they don’t.

And, actually, if you remove just 4 cities that have exceedingly low housing approvals: New York, San Francisco, San Jose, and Boston - even leaving in Los Angeles, Seattle, Washington, DC, and Austin - the standard deviation goes back under 13%.

The two ovals in Figure 2 are identical. In 2018, where labor and capital are allowed to flow, incomes still generally stay within a range of about 10% around the average. Incomes don’t react to changing economics, populations do. But only if it’s legal.

The tragic bit is that labor can still move into the Closed Access cities. It just has to be matched with an equal and opposite move. And the way that reaction is induced is financial distress. Enough distress to leave your home region. Developed economy refugees.

Boston, Los Angeles, and New York would certainly be within the oval if they built more homes. It is easy to imagine that San Francisco and San Jose have a little something extra going for them, and if they approved some homes, they would likely end up down and to the left, a bit above the oval, around Seattle. If they approved a lot of homes, they’d be over at the far right, just inside the oval, where Austin, the true superstar, is.

The natural state of a free economy is within that horizontal oval. Productivity can’t move you out of the oval. Only exclusivity and distress can.

I’m not saying that cities aren’t productive. I’m saying where productive cities actually grow, everyone benefits (even people outside those cities). The gains are shared. Where productive cities don’t grow, gains go to parasitical land owners and are canceled out.

Any attempt at quantifying the value of cities must start from the position of the free economy. San Francisco is so far from that, its local income norms are not a reliable proxy for that value. How expensive would San Francisco be, and how high would the average income there be if millions of its poorest residents hadn’t been displaced? How many touchdowns would Bo Jackson have scored if he hadn’t dislocated his hip? It’s really impossible to guess.

On the question of which cities are the success stories of the American economy, too many have been fooled into looking at the y-axis in Figure 2, when the answer is found on the x-axis.

I’ve done figure 2 using UK data. It’s checks out https://ibb.co/Pzbmy6C

I like the emphasis on how nimbyism has led to millions of the poorest residents being displaced. This is not usually emphasized enough.