This is a less complicated post than I usually write. But, I think this might be a useful visualization for thinking about urban housing supply. I’ve been posting some version of these types of charts for 8 years, but sometimes it’s worth taking a moment to revisit the hits. Nothing here is going to get published in an econometrics journal, but sometimes it doesn’t take anything complicated to see what is obvious.

Here, I think it might be useful to divide American cities into 3 categories:

Expensive, supply-constrained cities

Growing cities with moderate, but above-average home prices

Affordable cities with below-average home prices

Figure 1 shows the 20 year population growth of the 36 largest metro areas. (I chose 36 because San Jose is #36 and I wanted to make sure it was included. The patterns are the same, regardless of how many metros you include.) There are two types of cities with below average growth rates - very expensive cities and affordable cities. These are easily distinguishable groups.

The first point this chart makes clear is that the most expensive cities are overwhelmingly low-growth cities. Seattle is the only one that grew faster than the US average. LA, New York City, and Boston fall between St. Louis and Cincinnati. The other very expensive California cities fall between Cincinnati and Kansas City.

St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Kansas City are perfectly fine places to live, and, in fact, as far as we can infer, they are better places to live than the expensive cities. You might scoff, but Kansas City grew nearly twice as much as the average expensive city. Cumulatively about 10% faster over 20 years. A 10% increase in housing supply could make quite a dent in housing costs. If those cities grow by 10% and are still expensive after that, they can test the hypothesis that they are better places to live than Indianapolis or Columbus, which have grown about 15% more over the past 20 years than the typical expensive city.

The amount of catch-up the expensive cities have to do is substantial.

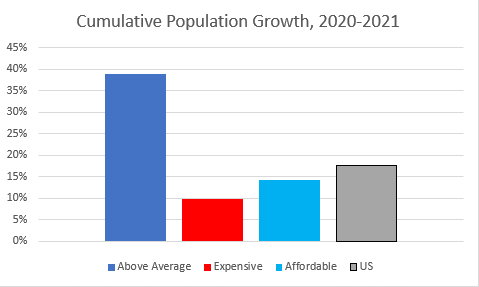

Figure 2 compares the cumulative 20 year population growth of the US, the affordable cities, the expensive cities, and the above average cities.

The most expensive cities are, by a long-shot, the slowest-growing group. If “superstar” status and high demand are what is driving high housing costs across the US, then this is the most unfortunate coincidence in the history of empirical economics. How did we manage to build all of our best cities in the places where average growth is impossible?

Finally, Figure 3 is a scatterplot comparing 20 year population growth with median home prices in September 2023. Let’s generalize these cities into 2 categories. Cities with above average growth have relatively elastic supply, and the higher the growth, the more elastic the supply. Cities with below average growth have inelastic supply. In some of them, growth and demand are so low that parts of the region are depopulating, so there is inelastic supply because of an existing stock of homes. And, some of them have inelastic supply because they refuse to allow it under any demand conditions.

There are 2 potential kinds of correlations here. A negative correlation would occur if more homes relieves supply constraints. A positive correlation would result if higher demand either (1) stresses local supply potential and temporarily raises the cost of land and construction or (2) higher population and more density create amenity value through factors like agglomeration effects (productive people working together, etc.) and there is no way to increase supply without permanently increasing local idiosyncratic cost of construction.

The cities with median home prices below $500,000 suggest some positive correlation. It is especially positive for the low-growth or negative growth cities, because supply is inelastic when demand is low or negative. And, there could be negative agglomeration effects in those cities. As you move into higher growth cities (Austin is the outlier on the right.), there is arguably still a positive correlation, though it is quite moderate.

The median US home prices is about $350,000, and the highest growth cities appear to converge at around $400,000. $50,000 in higher prices from local supply constraints or higher urban amenity value? Seems reasonable.

There are a group of cities with moderate, but not scorching, growth. Seattle is the most expensive. That group with about 20% to 40% growth and about $500,000 median home prices includes some other California cities, Denver, Miami, and Washington, DC.

Are these cities somewhat more expensive because they have more agglomeration and amenity value, or because they have inelastic supply? Again, if it is amenity value, the coincidence is staggering. Literally 13 major cities with potential agglomeration economies, and not a single one is capable of growing at historically moderate rates usually associated with valuable urban centers. The odds are staggering. How unlucky we must be.

Some questions we might ask: Are supply effects a reasonable explanation for the expensive cities (the orange dots toward the top)? The population-weighted average home price in those cities is about $800,000. What if they had grown by an additional 80%, putting them on par with Austin, over the past 20 years? Could an 80% rise in supply have lowered home prices by 45%? Absolutely! That is actually a pretty moderate demand elasticity.

What if the most important factor is amenities and agglomeration? What if San Francisco or New York City would only become more expensive if they build more housing? What if all those cities where the median home is more than $500,000 are more expensive because they are special, and they become more special as they get larger?

If they had grown by 80%, would the median home now be selling for $1.5 million in all of them? Would there be a bifurcation of cities? All the cities that have actually grown by 40% to 80% in the last 20 years add no value when they grow, but all the cities that didn’t grow would only become more valuable if they were larger? So, if they had, we’d have a bunch of superstar cities with multi-million dollar homes and a bunch of cities that grow even though they don’t add value?

As a binary proposition, the answer is obvious. Supply trumps amenity value. There seems like there could be room for equivocation. Maybe it’s a little of both. Maybe if San Jose (the most expensive metro) had grown by 80%, there would have been some supply effects and some amenity effects, and homes there would still cost $800,000, or $1 million, or $1.5 million, or $2 million.

But, that middle-ground is not particularly plausible. Thirteen of these major metropolitan areas have median home prices above $500,000. That’s thirteen to one odds against the amenities and agglomeration story having any substantial effect. If just one of 13 cities could have managed the growth rate associated with any of the Texas cities, the hypothesis could be tested. Until that happens, why would you stake any sort of importance to the idea? How big of a coincidence do we require the counterfactual to overcome?

To a first approximation, there is no debate. Do agglomeration or amenity effects exist? Sure. Are they important? Eh. If the supply problem wasn’t extreme, maybe there were would agglomeration effects to measure, and we could have interesting conversations about how the median home in Los Angeles is $520,000 while it is only $470,000 in Austin, even though they both have similar supply conditions. But, we happen to live in a time when constrained supply dominates the market.

Owner-occupied real estate has increased from 80% of GDP in the 1970s to 160% today. If the expensive cities had grown by 80% over the past 20 years, is there any doubt that the total value would be lower as a result? In supply constrained contexts, housing demand becomes inelastic. Households spend more when there is less to buy. If we added 20 million well-placed homes to the American housing stock, the total value of the American housing stock - including those 20 million extra homes - would be lower than it is today. More supply would lower housing costs, on net, and it isn’t even close. It certainly isn’t close in the cities that haven’t tried it.

Good post. There was an article in the Economist about migration trends in California which painted a more sophisticated picture of the "Great Exodus" which corresponds to trends in house prices and house construction across the state--basically what you show in some of the graphs above. California is shedding population from its rural areas like everywhere else. Where these people go is a function of housing affordability.

I understand this less complicated post.

As an aside, there is a little kerfuffle going on, after Paul Krugman said Americans do not understand how good they have it. Commentators like Matt Taibbi are mocking Krugman.

I think housing must play a large role in this tension between academics saying living standards are higher than ever, and ordinary Americans saying they are not.

When an average house in L.A. costs $1.2 million, and the picture is not much different anywhere along the West Coat, or NYC...and rents reflect housing scarcity....there are large swaths of the population who are not prospering.

Per capita incomes are one measure, and also reflect the rising incomes of post-retirement people, relative to earlier eras.

BTW, young men, adjusted for inflation, make less now than in the 1960s.

And, of course, anyone living in Detroit or similar areas would have qualms about "life is better than ever" narratives. But hey, you can afford housing.

Interesting topic, and housing is at the core of a lot of these problems.