I have written a couple times about how the Midwest was especially harmed by the policy errors inflicted in 2008.

There are the Kalamazoo posts. The first post of the “When we lost our minds” series goes into it. You can see how permanently hurt the Midwest has been in the charts here.

In a nutshell, the mortgage crackdown mostly blocked the purchase of affordable homes in cities where incomes are lower than average where there had never been a building boom or a price bubble. Seventeen years later, still, whole regions have been devastated by this and somehow few see it. Oh you want to bring back NINJA loans! Yeah! That worked so great last time!

Anyway, consider that background with this tweet from the Director of Research at John Burns Research & Consulting:

The conventional reaction to that would be that it is great news for Canton. Ohio must have a growing economy, strong incomes, etc.

Unfortunately, nothing about that is good news.

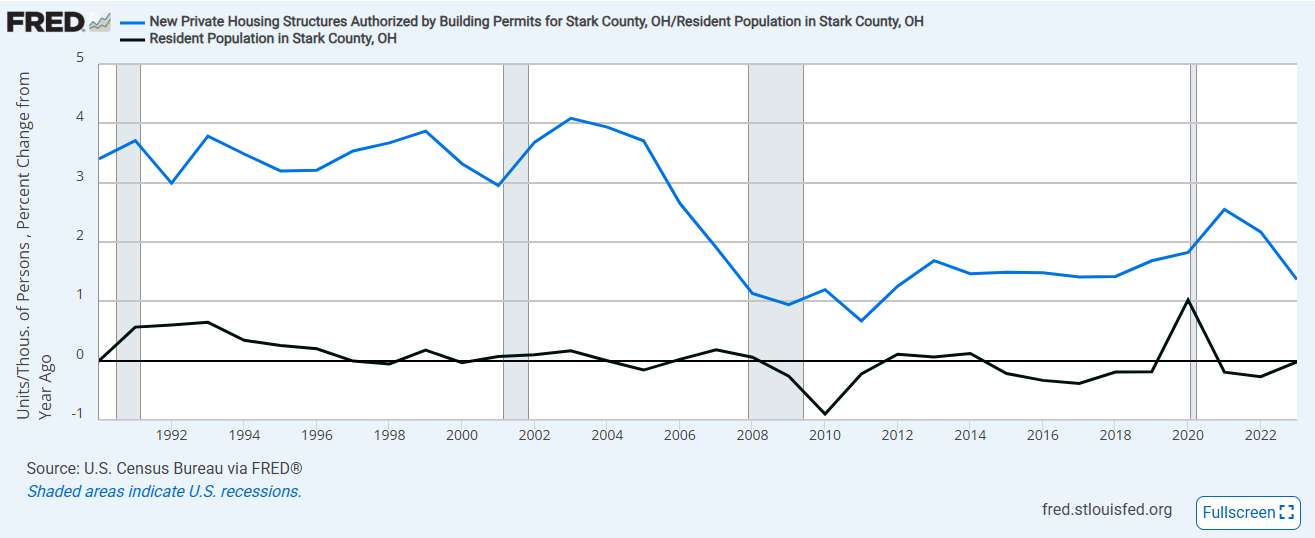

Figure 1 shows new homes per 1,000 residents and population growth in Canton since 1990. Population has basically been flat for the entire 35 year period. So, for the 15 years leading up to the financial crisis, about 3 homes per thousand residents was basically a maintenance rate of construction.

As in most places, construction was already declining in 2006. One reason was that the Midwest was early to recessionary conditions. Another reason was that the Federal Reserve was targeting a decline by 2006. Without the mortgage crackdown in 2008, there would have been a pretty deep cycle, probably bottoming out above 2 units per thousand residents in 2007, and then it would have presumably moved quickly back up to the maintenance construction rate of 3 units or a bit more per thousand residents by 2008 or 2009.

Instead, it has been permanently pinned below 2 units per thousand residents annually.

And, how do price and rent trends look in Canton in Figure 2?1

They look like the line chart version of my bar chart about what conceptually has to happen to prices and rents after a mortgage crackdown.

There was a small bump in permits in Canton from 2019 to 2022. Maybe rents have risen enough in Canton to finally induce new building again. Of course, the marginal increase in homes will have to be rental homes.

I suppose there will be a burst of single-family build-to-rent activity. The locals will decry Wall Street coming in and pricing regular families out of housing. And some righteous and popular local politician will quickly get a law passed to put a stop to it.

Then, they will complain about having more immigrants than they can handle and about how drug abuse and mental illness are creating a homelessness problem in Canton. The fine folks of Canton will throw their hands up. You can’t even help these people. What’s happened to this country?

The Closed Access cities on the coasts were supply constrained by local land use rules before 2008, so they have been in that condition for a while. Really, you could say that the entire Northeast is constrained in that way - every state east or north of Ohio.

Figure 4 compares per capita housing permits in the Northeast to Canton. The Northeast has only been growing by about 0.3% annually for 50 years now. Its housing production was only just a bit above maintenance level in the late 20th century, and now is probably slightly below it.

The Northeast - an area with about 58 million Americans - is basically locked down in its own chosen Malthusian limit. Growth of people or incomes can only be mitigated by lower housing standards, more intensive housing usage, outmigration, or pandemics.

So, mortgage access wouldn’t help the Northeast much. The growth of supply chain capacity and the emergence of the build-to-rent market won’t help it much. I’ve been watching the proliferation of anti-corporate housing bills. I suppose the Northeastern states could go to town with those horrible bills. Pass a rule that all housing has to be built with pasta. It doesn’t matter. Closed Access turns all good things into bad things anyway, so it doesn’t matter if you just do bad things instead of good things. They just change the margins where trade-offs are made. They can’t make the system any better or worse. It’s like putting a heavy lid over your rising dough. You’ve got a lot of leeway to mix your ingredients poorly, because mixing them correctly isn’t going to turn out well anyway.

And, as far as the rest of the country goes, the Northeast is your perverse proof of concept. Whole regions are capable of creating local conditions that make suffering inevitable. The rest of us could easily do it too. We’re not that far away from it now. It’s actually very easy to collectively create secondary effects that necessitate suffering. We’re probably history’s anomaly for having avoided it in many ways for some time.

A small bit of related market analysis for subscribers below.

By the way, this is a great example of how defensive the homebuilding sector is. The story of Canton is the story of the entire Midwest. New home sales in Canton could double from here. At some point they will. Nothing can stop them from doubling except for legally banning them.

For the Midwest, eyeballing Figure 5, that’s close to an additional 100,000 units annually, just to get back to sustainability. And, the Midwest probably accounts for about 2 million units of the accumulated shortage.

Construction isn’t going to decline in the Midwest from here, while rent inflation continues to rise (Figure 6)? (By the way, Figure 6 uses CPI rent data. The big dip in 2021 is from a methodological lag. The dashed arrows are closer to the true trajectory. The Canton estimate uses Zillow data, so it doesn’t have the dip. However, there are methodological mismatch between it and the other measures, including the lack of Zillow data before 2015.)

Build-to-rent is taking off where rent inflation has accumulated enough to make new entry-level single-family homes viable again. Where it hasn’t yet, rent inflation will continue to accumulate until it does. We’re deeply into a constrained supply context in a sector where demand under constrained supply is inelastic. The fewer homes we build, the more families will spend in rent, in the aggregate, to use them. There is no down button in this elevator.

I guess we could have a big income shock. Who knows what will happen with the Trump administration back in power? But rents aren’t rising because of rising incomes. Rents are rising in spite of incomes. Cross-sectionally, rents are rising the most where incomes are lowest. I’m not sure an income shock associated with a typical recession would make much difference.

Trump’s minions might end up tightening mortgage access even more if they start playing around with trying to privatize Fannie & Freddie. I’m not sure that even matters at this point since the marginal new construction is going to be build-to-rent.

Now let’s think about the South and the West. New home sales have recovered in those regions more than the Midwest. But, do you think that means they are done? The rate of construction there isn’t back to sustainability either. Rents are still rising. Those regions probably both need more than 100,000 units annually to stop rents from continuing to rise. And, together, they probably need more than 10 million units to reverse the accumulated rent inflation.

The huge scale in these clear deviations from traditional market behavior, the obvious signals of supply constraints, and the importance of the mortgage crackdown in creating them haven’t been able to break through the public’s perceptions, so this big obvious analytical gift horse is just sitting there to use to allocate capital in ways that the market isn’t going to price right.

When I say that the industry is building at capacity, operators are sometimes indignant. Like, it sounds nuts to them to say that. Then, I’ll ask why construction schedules on new homes are bloated. And, they’ll answer some version of, “We can’t find workers. We can’t get financing. We can’t get materials.”

It’s weird. I think, maybe they are benchmarking to construction capacity from 20 years ago, and so it seems crazy to claim that capacity could be so much lower now. But, that just speaks to the depth of the supply constraint. We permanently unemployed about 40% of the residential construction workforce. We did it on purpose. I’m sure the damage ripples through most of the residential supply chain. We could have gotten that capacity back in 2009. Now, we are dealing with the hysteresis of lost decades. We are going to have to grow capacity again as if we’ve never had it before. This is going to be a long slow process.

At the macro level, the pundits and economists who should have been vocal allies of markets were convinced we had millions too many construction workers and that we had to have a long painful reorientation to patterns of sustainable specialization and trade. So, we pushed 2 million workers out of construction trades.

Industry insiders now look at an employment market that had actually been pushed and held out of sustainable equilibrium, and they think, “Nobody wants to work anymore.”

As it stands, anyone who hasn’t flipped their mental framework upside down about how cycles work in this industry is just going to keep being confused. Anyone who thinks housing starts are, or will soon be, demand-constrained, is disengaged with some stark, obvious realities. (And, here, to keep from being confused, it is important to think of homebuyers as suppliers more than demanders. Households who can’t get mortgages have created a supply constraint.)

Accumulating 30% excess rent inflation in a decade, as the West has, is absolutely whackadoodle. So is accumulating 10% excess rent inflation in cities with stagnant population in the Midwest. If you’re modeling this market the same way you were in 2005 or 1995, you’re looking through the wrong end of the telescope.

My inflation adjuster is CPI excluding shelter plus 0.8% annually to account for upward drift in Zillow estimates due to compositional changes in the housing stock over time.

For some reason I'm annoyed that you're right about this. Probably because for many years I've bought into the notion that the American Heartland was a forsaken, hopeless waste because of technological change and the outmigration that came along with that. Curiously, population trends in the Northeast were similar to the Midwest from 1970ish to 2000ish for the exact same reasons--although the Northeast replaced incumbent industries like textiles with more expensive stuff like computers and biotech. From 2000 to 2006 there was a resurgence of homebuilding that was then stabbed to death by Fed actions. Granted, there are cities that are making a comeback, but the trends in places like Canton are not good because of the mortgage access problem. Ironically, the affordability of older houses in many parts of the Midwest has a dampening effect on any type of improvement. "Look how cheap those houses are-no one would want to live there!"

Off topic, the Economist article on housing in Taiwan was simply bizarre. Whenever I think the U.S. has taken the trophy for bad housing policies I read about places like that or Ireland or the U.K.

Off/On topic the piece in the Atlantic about the reasons for mobility declines in this country. We have met the enemy and she is......Jane Jacobs.

Another superior report on housing from KE.

Side thought: Tell your kids to go into something related to housing rehab, fix-up, repair.

America's housing stock is aging about one year for every year, there is so little new construction. Pipes get old, wiring dangerous or outdated, roofs leak, timber rotted and so on. I don't think AI can solve this one.

Fixing cars is another trade. The average age of car on the US road is now more than 12 years, and rising. Again, these are one-off situations, not something AI can do.

Side note:

This problem of expensive housing seems widespread, even globally. Aussie, Canada, Hong Kong, South Korea, UK. Whole populations have moved into decline.

Something about urbanity.

Orthodox macroeconomists say, "No problem. Just offshore having and raising babies."

I wonder.