"Reassessing the role of supply and demand on housing bubble prices" (Part 5)

Congratulations, we just played ourselves.

So, in the previous installments (Parts 1, 2, 3, & 4), I re-assessed the factors that moved home prices from 2002 to 2006, using my new variable that captures the effects of constrained housing supply on a metro area’s home prices. I found that, in order of importance, factors associated with home price appreciation from 2002 to 2006 were:

metro area differences (fixed effects)

supply constraints (price/income slope in 2002)

factors outside the model (residuals)

credit access (FHA market share and mortgage denial rate in 2002)

speculation and trend continuation (non owner-occupier market share in 2002 and 2001-2002 price trend)

My variable helps to isolate the effects of credit access on home prices, so that even though my variables for credit access are 4th on my list of importance, the scale of importance that I find for it is at least as strong as in the existing literature. The existing literature has simply chosen to ignore the 1st and 2nd most important factors, which is somewhat understandable because they didn’t have a variable that could measure the effect of supply constraints independently in real time. I have found that variable. So, now, we can talk about the factors driving 80% of the change in home prices rather than limiting ourselves to 5% of the change and inferring total effects from that.

Furthermore, the credit access factor is negatively associated with the other factors. Credit access was associated with rising home prices in places where prices increased the least. This is the last factor that should have been reversed in order to reverse high prices, but it is the factor that eventually the most important public policies targeted.

Let’s look closely at what happened next, from 2006 to 2010. Table 7 from my paper shows the average directional effect of each factor during the boom and during the bust. For instance, the price/income ratio on the average home from 2002 to 2006 increased by about 24.4% (0.244 log points to be precise - in other words, 24.4% continually compounded). Of that 24.4%, 4.2% was associated with speculation variables (non owner-occupier buyer market share and pre-2002 trends).

Keep in mind, these are averages. In all cases, there was a wide range of sensitivity across ZIP codes. In some places, prices went up or down a lot because of city-wide trends, in others because of housing supply or credit access. So, for instance, MSA fixed effects (the difference between cities) was associated with almost a 20% rise in Phoenix and almost a 20% decline in Atlanta. A lot of variation, but averaging to zero.

Let’s start at the bottom. My analysis doesn’t capture much change due to speculation, and that small change partially reversed from 2006 to 2010. Not much to discuss there.

Credit access (roughly, the price/income change in the average ZIP code with 16% FHA market share and 14% denial rates that is associated with changing credit access after 2002) was associated with an average increase of 8% during the boom, which was completely reversed during the bust.

As I discussed in part 4, where credit access was associated with higher prices, the other factors were associated with lower prices. But, ignoring that for the time being, I suppose you could say there was an 8% credit bubble that was countered when credit tightened. And, again, these are averages, so, as the last graph in part 4 shows, generally, this meant that price/income ratios in many cities went up and back down by around 16% in ZIP codes with low incomes while there was little effect in ZIP codes with the highest incomes.

Next, supply constraints were associated with an average rise of 15% from 2002 to 2006 which only partially reversed. Again, this is an average between ZIP codes in LA, New York, Boston, and San Francisco that rose more while supply had little effect on prices in many cities.

Finally, there are the controls and the effects of metro area differences. Think of this as the change in price/income from 2002 to 2006 for the average home in the average city, with no local supply constraints, zero FHA market share, no denials on mortgage applications in 2002, flat prices from 2001 to 2002, and all mortgages going to owner-occupiers. More or less, a ZIP code with very high income in the average city.

The price/income ratio on that average home actually declined from 2002 to 2006, by 2.6%. In part 4, Figure 2, Altanta and Detroit were examples where this was the case. On average, in other words, rising home price/income ratios were entirely accounted for in this regression by supply constraints, credit access, and speculation. Then this price/income ratio declined another 8% from 2006 to 2010.

While the ups and downs of the other factors happened through the reversal of the averages. The ups and downs of the cities happened through the differences between cities. Prices in some cities, like Phoenix, shot up from 2002 to 2006, and then collapsed from 2006 to 2010. In other cities, prices weren’t particularly volatile.

Figure 8 from the paper compares uniform changes in price/income ratios within each metro area from 2002 to 2006 (on the x-axis) to changes from 2006 to 2010. So, for instance, homes in Phoenix experienced a shared gain of just under 20% from 2002 to 2006 and then a shared loss of about 40% from 2006 to 2010. For each 1% gain or loss from 2002 to 2006, the typical city experienced about a reversal to a 0.7% loss or gain from 2006 to 2010.

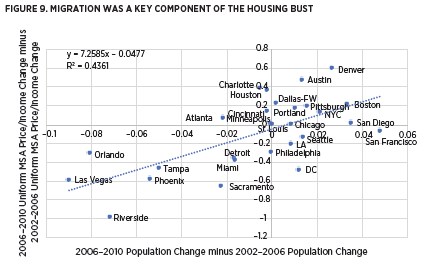

A thousand papers have been written trying to figure out what banking rules or lending changes could have accounted for these differences. Much of the difference came from population shifts. Figure 9 from the paper compares the boom to bust price trend changes to changes in population growth. The outliers in Figure 9 in the lower left quadrant all had population booms from 2002 to 2006 that suddenly reversed and also had rising prices from 2002 to 2006 that also suddenly reversed, giving them highly negative values in both measures. In all cases among those outliers, the marginal changes in population growth were largely due to families moving out of the cities where supply constraints were driving prices up and families away.

So, we have three main sources of boom to bust reversal. The acceleration of rising prices in housing-constrained cities, which only partially reversed. A rise and fall in regional home prices due to population shifts, much of which was caused by the families moving out of the housing-constrained cities and then staying in a them when prices from supply constraints relented. And, finally, a rise and fall in home prices associated with changing lending standards, which was unrelated, or even at odds with, the supply-induced price volatility.

Figure 1 shows price changes from 2006 to 2010 in selected metro areas, arranged by ZIP code incomes. (The left panel shows changes in price/income. The right panel shows changes in nominal prices.) Where incomes were high, prices didn’t decline that much. Where incomes were low, prices collapsed outrageously in many cities.

Looking back to Table 7, the end result of 8 years of boom and bust was the combination of (1) a general decline in prices across the whole 8 year period, summing to more than 10%, (2) the rise and reversal of credit-related price changes, (3) the continued separation between expensive, supply-constrained cities and less expensive cities.

As I wrote in the paper:

Taken as a whole, these results suggest that the key factors over this period were secular, not cyclical. On balance, the country’s stock of housing was bifurcating into housing in markets with elastic or inelastic supply. The housing where supply was inelastic was persistently diverging to higher prices (especially for residents with lower incomes), while prices of housing elsewhere declined relative to incomes. A credit boom may have temporarily sped up the process of migration, filtering, and economic segregation driven by inelastic supply. Then when the credit boom reversed, the process slowed down.

The debate between credit supply and speculation that has not adequately focused on housing supply has lent itself to the presumption that, whatever the causes, this was a story of a bubble and its reversal. As table 7 highlights, that framework for thinking about the period misses some of the most important facets of the changing housing market. One complication to consider is that a primary motivation for the credit boom was to escape the expensive housing-deprived cities.

Figure 2 highlights this shift. This shows price changes over the whole period from 2002 to 2010. On a price/income basis, Detroit was down more than 40% across the city. Price/income ratios at the high end of Phoenix (a “bubble” city) and Atlanta (not a “bubble” city) ended up about where they had started while at the low end they dropped by more than 20%. And price/income ratios across LA were up by double-digits.

In Figure 2, you can see the story of the death of American working class housing by friendly fire. The difference between LA and the other cities, driven by its ridiculously low housing production, was the primary motivator of all of these events, and by 2010, nothing that had happened had interrupted that process. There is evidence in this work that increased lending had been facilitating demand for second-best options in more affordable cities where housing could be more amply constructed. And, the main result of cracking down on that lending was that the most economically vulnerable homeowners in those second-best, more affordable cities were devastated. Suddenly we made them more affordable than ever by interfering at the federal level with the mortgages that buyers of those homes needed to buy them. And, in the meantime, the most expensive cities just got more expensive.

The various parts of the boom and bust added up to a lot of regressive inequity.

Long-time readers might notice that Shut Out contains charts that convey a basic version of Figures 1 & 2. These recent papers allow me to quantify these effects more precisely in real time.

Very observant readers might notice that there are some incongruities between my regression results and the price changes shown in Figure 1. I will discuss those in one final post about this paper.

"The death of American working class housing" could be the title of your next book--or maybe simplify it to "The Death of American Housing"--because dramatic effect is important. What's important about your research is that you offer a potential solution to some aspects housing shortage that could be implemented at the Federal level. I'm thinking along the lines of the following:

-More robust FHA support for low income, first time homebuyers (kind of like how it worked from 1950 to1979)

-More rational lending standards for private banks that restore most pre-2006 conditions

-Better regulation of the securitization of low credit mortgages

-Application of civil rights legislation and judicial review to local zoning codes (Waaayyy more controversial than my other suggestions!)