"Reassessing the role of supply and demand on housing bubble prices" (Part 4)

Was the lending boom mitigating the housing bubble?

In Part 3, I wrote that by using my “supply” variable in regressions of changing home prices from 2002 to 2006, in my most recent paper, I was able to find stronger effects from credit access than regressions without that variable found (to my surprise!). Yet, even with those stronger effects, changes in home prices associated with my credit variables were still smaller than changes associated with the lack of supply or the metro area a home was in.

In this post, I will dig a little more deeply into how credit access interacted with incomes and with the other factors that were associated with changing prices.

As Mian and Sufi point out in one of their earliest papers on the housing boom:

The expansion in mortgage credit from 2002 to 2005 to subprime zip codes occurs despite sharply declining relative (and in some cases absolute) income growth in these neighborhoods. In fact, 2002 to 2005 is the only period in the last eighteen years when income and mortgage credit growth are negatively correlated.

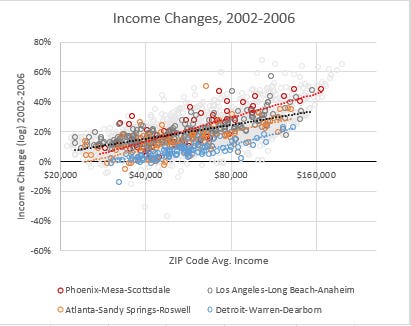

There was a lending boom, and it was associated with some buoyancy in home values. One anomaly about the period is that income growth was pretty uniformly top-heavy. So, across the country, urban neighborhoods with low incomes also tended to have low income growth, at least as measured by IRS adjusted gross income.

So, this leads to an interesting pattern in home price trends from 2002 to 2006. Simply looking at nominal price trends (Figure 2, right panel), price changes within each metro area are relatively similar, regardless of income - except for LA. In most cities, the city mattered a lot to how much a home’s price changed, and income levels mattered very little.

But, looking at price/income (which is what I did in my paper), since incomes increased more where they started out higher, price/income ratios increased more in every city in ZIP codes with low incomes than they did in ZIP codes with high incomes. This is due to a difference in income growth rather than a difference in home price appreciation. In Atlanta and Detroit, price/income ratios actually declined in ZIP codes with higher incomes.

In the previous posts on this paper, I argued that there is a bit of a riddle in the data on lending access for home buyers with low incomes and home price trends. The places where home prices increased the most in ZIP codes with low incomes were the places where households with low incomes were migrating away at rates so high they became disruptive to the cities they were moving to. If loose lending to borrowers with low incomes was an important element in rising home prices, it would be strange for population flows and price trends to be so at odds with each other.

In Figure 3, I subtract the price changes I associated with constrained supply. This erases much of the difference between metro areas. With that adjustment, price changes are relatively flat in each metro area, and changes in price/income ratios still have a slightly negative correlation with income.

Now, let’s take this in another direction. In Figure 4, I subtract the price changes that I associate with credit access. With that adjustment, Los Angeles looks more different than the other cities. Also, changes in price/income ratios are relatively flat in the other cities, while changes in nominal home prices are positively correlated with incomes. In fact, according to my regression, without the price appreciation associated with credit access, homes in the poorer neighborhoods of Atlanta and Detroit would have declined in value - in nominal dollars - from 2002 to 2006, and price/income ratios would have declined throughout those cities.

And, so, the irony of the bubble narrative takes an even deeper step. The conventional wisdom on the housing boom sort of throws all this evidence into one big “American housing market” stew, and says, “Home prices were rising outrageously, and loose credit was systematically associated with those rising prices.” But, really, when you account for the importance of local supply conditions, the story is, “Home prices were rising outrageously where housing is in short supply. That led hundreds of thousands of families to move away from expensive places. At the same time, a credit boom was associated with a stabilization of home prices in places where prices would otherwise have fallen.”

If there is room in that more comprehensive narrative for cursing the reckless mortgage lenders and housing speculators, it is much more subtle than the “The financial crisis was the result of bankers creating a housing bubble!” narrative that populates countless shelves at your local library.

As I mentioned in Part 3, there was a positive correlation between FHA market share and denial rates on new mortgages and price/income changes from 2002 to 2006. In other words, where credit access is normally the most constraining, prices rose more. But, the interaction between those variables and the supply constraint variable was negative. In other words, in cities like Los Angeles, which are very expensive because of supply constraints, FHA market share and denial rates had a weaker association with rising prices than they did in more affordable cities.

That makes a lot of sense, because the types of families that use FHA loans or get denied on mortgage applications were flooding out of cities like LA during the lending boom.

Looking at the data nationally, this leads to a bit of a paradox. My regression estimates that, all else equal, the average ZIP code from 2002 to 2006 saw an increase of about 8% in its price/income ratio, associated with looser credit conditions. But all else wasn’t equal. It may be the case that a lending boom happened that was completely at odds with the supply-deprived housing boom. In fact, it may be the case that the lending boom operated in opposition to the housing boom.

In Figure 5, the x-axis shows the change in price/income ratios associated with looser credit from 2002 to 2006 (including the interactions with the supply constraint variable). ZIP codes where the FHA had no presence and where borrowers were never denied loans, of course, have no sensitivity to credit conditions, and so they are near zero on the x-axis. ZIP codes where denial rates were high and FHA loans were more prevalent are farther to the right on the x-axis. Credit was associated with higher prices.

The y-axis shows the actual measured total change in price/income ratios. And, the oddity here is that there is a negative correlation between price/income changes associated with credit access and total price/income changes. In other words, a ZIP code that had had higher denial rates and higher FHA share in 2002 was likely to have experienced less price appreciation from 2002 to 2006 than a ZIP code with no denials or FHA activity.

Credit access was associated with rising home prices in places where home prices weren’t rising that much!

In the conventional story, subprime lenders in Detroit and Atlanta are just another B-plot in a litany of extremes. The story informed by housing supply is that we were segregating national according to housing costs. And, in that story, maybe home prices stabilizing in some of the least-favored locations was part of that process - families with low incomes buying homes in affordable cities. Figure 6 shows price/income ratios in 2006 in these metro areas.

In parts of Atlanta and Detroit where incomes are low, the cost of mortgage payments is typically well below the monthly rent payments for the same house. And, if I might take this a step further, when our “housing bubble” confirmation bias receptors were being dosed by the collapse in home prices from 2007 to 2012, did anyone wonder about these cities? In cities where price/income ratios were quite low and hadn’t deviated by more than 10% why did they need to subsequently get cut in half? (More on that to follow.)

There’s an old saying that you can’t reason someone out of something they weren’t reasoned into, and I think there is a version of that here. In the conventional story, there’s a mish-mash story of home buyers with double-digit price/income ratios in Los Angeles and of an increase of subprime borrowing in Detroit, which serves to explain the subsequent collapse in both cities. There are anecdotes of predatory lending in both contexts. But, these are very different stories. There is evidence of a lending boom in Detroit and Atlanta. There is little evidence of a housing bubble in Detroit and Atlanta. But, questioning the analytical evidence for a housing bubble in Detroit or Atlanta doesn’t go very far when the conventional wisdom is so dependent on anecdotes. “I saw lenders handing out loans to buyers who had no business taking on a mortgage” might be a factually accurate statement in a large number of cases, but the mish-mash story became canon without carefully connecting those anecdotes to local rates of housing construction or price appreciation. If the canon was written without that careful connection, it isn’t going to be easily re-written if that connection is retroactively reexamined and found wanting.

A lack of housing supply drove American home prices unsustainably high after the turn of the century. Maybe the lending boom, for all its faults and over-reaches, was facilitating a market in compromise, funding the mass migration away from high costs. Unfortunately, instead of solving the supply problem, we hobbled lending markets. And, in the process, we have only made matters worse for America’s working class citizens in the subsequent years.

The 2006-2010 lending crackdown and price collapse will be the topic of the next post.

PS. Here’s a chart showing the changes in price/income ratios from 2002 to 2006 associated with credit access (FHA market share and denial rates) in this regression.