In yesterday’s post, I mapped Fannie Mae’s credit data to the national data to try to get a broad sense of current lending conditions relative to past decades. The one detail I can’t review using the national data that I used in that post is the value of homes getting new mortgages. I could compare the mortgages outstanding to the total value of real estate outstanding or to GDP, but the New York Fed data on mortgage originations isn’t packaged with data on the value of the specific homes those new mortgages are funding.

I thought it might be worth briefly revisiting the topic to add some color on that issue, using Fannie Mae data that dates from 1996 on home values and loan-to-value, and from 2000 on credit scores.

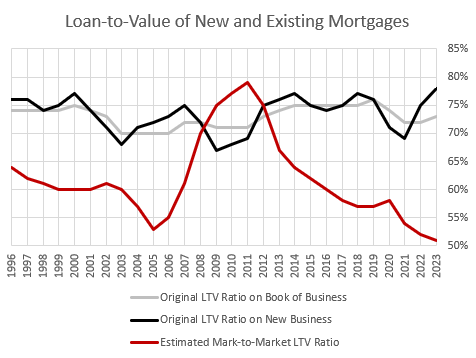

Figure 1 shows loan-to-value (LTV) on Fannie Mae loans, both new and existing.

Side note: I think there is a natural tendency to worry about reckless lending, and an observer’s bias from the fact that witnessing more seemingly risky borrowing is more salient than observing less risky borrowing. So, I think there is a sense among the public, and especially among cyclically sensitive investors, that standards and terms are constantly loosening - that “Back in my day, you saved up a 20% down payment and did it the right way, and now they have these programs to give mortgages to 600 point credit scores with 3% down.” Sort of like how a portion of the public always believes that education spending is always declining even thought it is almost always rising.

The average down payment hasn’t changed over time. The original LTV on the book of business is currently 73%, and it hasn’t been more than 3% above or below that since at least 1996.

The mark-to-market LTV highlights a couple other issues. One really tricky aspect of the public mythology about the 2008 crisis is that it is universally attributed to activities that generally happened around 2006. But, most of the damage that informs the scale of the crisis happened after 2008. The median point for excess foreclosures was the 3rd quarter of 2009. And, the losses on collateral were deeper on the later foreclosures. Peak unemployment was October 2009, and it remained above 9% into 2011.

The weighted average mark-to-market LTV spiked up in 2008, but it continued to rise until 2011. In other words, the lost equity that was the main trigger for the extra defaults kept getting worse until 2011.

So, it’s not just that financial stresses in 2008 were allowed to happen because they were blamed on activities that happened in 2006 and were greeted with fatalism. Financial stresses in 2011 were treated the same way. And that fatalism is the reason the costs of the crisis loom so large.

The only reason that the decline in home values was allowed to go on for so long is that the myth that high prices were entirely a product of excess demand (low interest rates, loose lending, tax breaks, etc.) was nearly universally accepted. Deeply discounted home prices were still being treated as elevated. The myths were still suffocating the market in 2011, years after deep cuts in mortgage access were the main driver of the suffocation.

The other thing I’ll note in Figure 1 is that the mark-to-market LTV is now at an all-time low. It bumped up briefly in 2020 when a lot of low LTV borrowers did cash-out refinancing. (Notice the average LTV on new mortgages declined, but the mark-to-market LTV on the existing book of business increased.) But, in general, it has been declining since 2011. Part of that is the unusual price appreciation of homes in general since then. But, I suspect part of it is the cohort of low-score borrowers who can’t tactically refinance and who can’t re-leverage into a new home, so they continue to pay down mortgages that now have very low LTVs.

Figure 2 is looking at the same LTV stats, but here I have disaggregated between the mortgages held by borrowers with <740 credit scores and >740 credit scores. LTVs on new mortgages remained about the same from 2000 to 2007, and the relative size of the 2 groups remained about the same. Then, from 2007 to 2009, the average down payment increased (LTV was lower) and a much smaller portion of those mortgages went to borrowers with <740 scores. The proportions have remained pretty stable since then.

Looking at the existing book of business, the recovery of home prices has caused the mark-to-market LTV to decline since 2011. The balance for higher scores has stabilized in the past 5 years or so, but mortgages held by borrowers with lower scores continues to decline, relative to the total value of Fannie Mae collateral.

Figure 3 shows the average home price on new originations over time, and the portion of total Fannie Mae lending per home that goes to low versus high score borrowers. This helps highlight what changes in Figure 2 are from changing home prices and what changes are from lending standards and loan size.

Finally, in Figure 4, one significant point that the Fannie Mae data helps to clarify is the trends in the prices of homes on new mortgages over time. I have included this in several previous studies and posts, so readers may have seen this before.

From 1996 to 2006, the homes Fannie Mae was originating new mortgages for were similar to the homes Fannie Mae had originated mortgages for in the past. Then, from 2007 to 2009, the homes getting new mortgages changed sharply.

Maybe Figure 5 is the better way to visualize this. This is the difference between the value of homes with new Fannie Mae mortgages and homes with existing Fannie Mae mortgages.

There may have been some correction toward lending back into low tier markets, but keep in mind, even with a permanent change in lending norms, these measures would naturally reconverge as the cohorts of new homes become a larger portion of the stock of existing homes in the book of business.

I didn’t fully appreciate the causal import of this change, even when I wrote my two books. But, as a result of my Mercatus papers, and inferences from the Erdmann Housing Tracker data, I conclude that most of the downward trend in the home values in Fannie’s book of business and in the Zillow median home value (ZHVI) was caused by the trend in the value of homes getting new Fannie Mae mortgages. In other words, if the average value of homes getting new Fannie Mae mortgages had been $250,000 in 2010 (because Fannie was still lending to low-credit-score borrowers in low-tier homes), then the homes in Fannie’s book of business would still have had an average value of about $250,000.

Both the foreclosure crisis and the collateral value collapse were of Fannie and Freddie’s own doing, under pressure from federal officials.

The conventional wisdom is that the 2000s can be described as a lending bubble that then corrected. A boom with a necessary bust. In most American cities, the construction and home price data just has the bust. The time series for, say, home prices in those cities are not a spike and then reversal, like you would see on the real Case-Shiller home price index. They are just… nothing, nothing, normal, normal, normal, bust. They didn’t have booms or bubbles. Just busts.

The Fannie Mae home value chart is similar. Nothing, nothing, normal, normal, normal, bust.