OK. One more Moral Panic post

Just a quick correction. I probably overstated the change in lending standards a bit in the previous post.

I compared the average prices of homes getting new Fannie Mae mortgages in 2007 and 2009 to the distribution of home prices across US zip codes. It suggested that the effective market served by Fannie Mae was cut in half over that time.

In Figure 3, I take a more complete look at this estimate, showing the percentile rank of the average Fannie Mae home every year from 1999 to 2023. The jump from 2007 to 2009 does equate to basically cutting the served market in half. (The average Fannie Mae borrower in 2007 was more valuable than 66% of homes and in 2009 it was more valuable than 84% of homes.)

But, a significant amount of that was probably related to refinancing activity. Families with lower credit scores and lower incomes who live in less expensive homes tend to refinance more often in order to get cash or to cover some economic event, either to pay bills or make investments. Families with higher credit scores and higher incomes who live in more expensive homes tend to refinance more often to take advantage of lower rates.

So, when there is a refi boom related to low rates, the average credit score, income, and home value of new borrowers tends to rise. Also, since we have created a mortgage regulatory framework based on attribution error which imposes illiquidity on households in a procyclical and regressive way, families that could especially value the advantages of tactical rate-motivated refinancing are frequently locked out of that opportunity. They are less likely to be able to qualify for a mortgage at any given time, and they are especially less likely to qualify during times when rates are low because low rates are usually associated with economic downturns.

So, in Figure 3, you can see bumps in the Fannie Mae home value around 2003, 2009, and 2020, when there were rate-motivated refi booms.

Probably, the more persistent change in lending standards moved the average Fannie Mae home from about the 65th percentile to about the 75th percentile, rather than to the 85th percentile.

It may be more accurate to say they stopped serving a third of the market rather than to say they stopped serving half the market.

The more recent drop in the value of homes with new Fannie Mae loans is definitely not related to loosening mortgage access. I suspect it is a temporary compositional change having to do with the low amount of purchase activity, the high number of cash buyers, etc. I expect as the market recovers, it will revert back up to the 75% range.

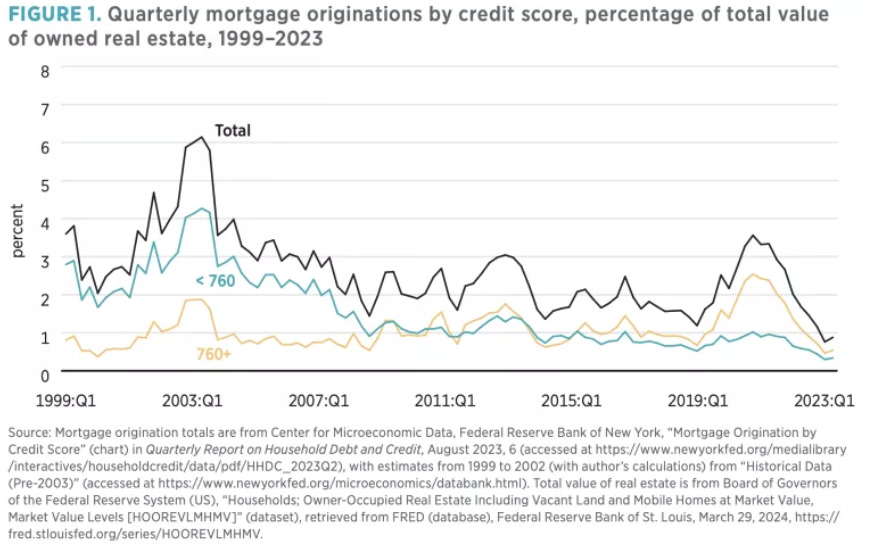

This comports with the change in the amount of mortgage originations associated with various credit score ranges, in Figure 4. It was cut by roughly a third at the same point where Fannie Mae’s data changed.

There are arguments one could make that the number of borrowers served was cut in half. Borrowers with lower credit scores tend to buy smaller homes, so a drop of 30% in the total value of originations that is correlated with credit scores probably equates to a decline of more than 30% in the number of loans.

I think one could argue that the change was between 1/3 and 1/2. But, the more defensible assertion is 1/3.

In very broad terms, about 20% to 25% of homeowners in 2008 lost access to mortgage credit. Since then, the number of mortgages outstanding has declined by about 15% and the number of owner-occupied homes has increased about 10%. The adult population has risen by about 15%.

So, of the approximately 15% of the current population that would have been mortgage borrowers in the before-times but cannot now - roughly 20 million households:

some portion remain in their homes making the remaining payments on their existing mortgages

some lost their homes in the foreclosure crisis

some are renters instead of owners

some didn’t form new households

I would expect that the majority remain in the homes they owned before 2008. That will slowly decline over time through attrition while new potential households that didn’t exist in 2008 will slowly grow over time. So, the change in credit standards showed up very quickly in new mortgage data, but it is showing up more slowly in household data and housing inventory data.

Now that rents have inflated enough to make the large scale new single-family build-to-rent market economical, I suspect we will see a boom in new rental households as it becomes more feasible for the credit-blocked population to form new households. The rise in single-family build-to-rent will create a rise in household formation.

While that market develops and while we re-build the stock of vacant homes, which will require 4 or 5 million additional units, there will be years of active home construction with howls of “bubble” arising from the supply-deniers who will note, year after year after year, that these new homes are unneeded because population growth doesn’t call for them and also vacancies will be rising.

This will likely all happen while mortgage rates remain above 6%, so it will be interesting to see what explanations will keep those supply-denier narratives going. Myths about the Federal Reserve and interest rates won’t work any more. Or, maybe, “The collapse will come soon.” can keep someone from correcting their understanding forever.

That may mean that undervalued homebuilders will remain undervalued for years even while their operations continue to grow.

This has been an interesting analysis for the past few weeks. While we've been fixated on the residential housing market, major sectors of non-housing commercial real estate have been in a state of collapse, panic, decay, crisis, etc....since the Pandemic. Or perhaps, the collapse, panic, destruction, etc....in CRE has been building for decades due to profligacy, greed, low interest rates, etc....AND SOMEBODY SHOULD DO SOMETHING ABOUT, BUT IT'S TOO LATE AND WE'RE ALREADY IN A RECESSION!!!!

No, wait, the churn in the CRE market is called "business" or "market forces at work" or "creative destruction" and the impacts on the broader economy have been muted by the fact that you can have upheaval in a sector without blowing up everything else. Perhaps in a different Universe there would have been a Fed that interpreted price declines in Manhattan office buildings as a sign that money should be tighter and restrictions placed on sales, transactions, and valuations for the next few decades.