Cyclical vs. Secular Housing Trends

In this post, I want to continue the discussion of the effect of new housing supply on residential property values at a more macro level.

In the previous post, I wrote that the effect of new supply is powerful over the long-term, but acts slowly and gradually. I pointed out that none of the sharp downturns in home rents or prices in the recent past have been the result of increased supply. And, further, I asserted that supply has never and will never cause a collapse of prices and rents. Under a 2% inflation target, comprehensive supply reforms might create flat, or at most, slightly negative nominal price and rent trends while nominal incomes grow and catch up.

There are several alternative views that I frequently see expressed. The view I was pushing back against in the previous post was the sloppy confirmation bias I frequently see in YIMBY circles, where lower rents that are mostly due to downshifts in demand are presented as proof of the success of new supply.

Salim Furth at “Market Urbanism” made a great analogy: “arguing about housing supply from short term fluctuations is like arguing about climate change based on the week’s weather. Keep your powder dry, promise slow change and long-term stability, and recognize that demand shocks are responsible for most fluctuations.”

Regarding urban housing, there are similar factions as in climate change - there are both deniers and overzealous cheerleaders. In fact, the existence of these factions on any topic with these parameters is probably inevitable.

The deniers come in several forms. There are closet NIMBYs who would like to think that empirical economic outcomes would favor their aesthetic preferences. There is the agglomeration school that came preset with a model that attributes price to value. There are homevoter hypothesizers who might think that the aggregate excess value of American housing is just the sum of all the neighborhood character that NIMBYs are protecting.

On the macro side, the deniers are on the right and left. On the right, Austrian and Minsky folks, the permahawks and permabears, the gold bugs, and the conservatives who disfavor various government interventions into housing. They tend to view the American housing problem as purely a cyclical one. They always want to take the proverbial punch bowl away. Too much money, too many mortgages, or too many subsidies are the problem, as they see it.

On the left, the social reformers, tax and spenders, socialists, and academic planners claim there are plenty of homes. They are just distributed poorly. We don’t need homes in general. We need the right kind of homes that only public funding will provide. They think markets will never provide basic needs for poor families and poor families will never get to live in homes that were built for richer families.

Housing supply skepticism is a big tent, politically. No pun intended.

They are all wrong in different ways. More homes absolutely will lower costs over time, but slowly. State policies that stimulate a building boom will help the solution, not worsen the affordability problem. Ample market-rate housing is the prerequisite for getting costs of public housing dispensation low and effective.

In this post, I will address the question from a general macro-level national perspective, under current supply conditions. Maybe, if my thoughts coalesce around it, I will add another post about individual cities and the potential of land use deregulation. But, here, I’m going to keep it “big picture”.

I think one of the tricky aspects of housing economics is that neither supply nor demand elasticity are linear. Housing is a bundle of luxuries and necessities. When it is lacking, we will pay whatever we have to for it. When it is abundant, we will pay what is comfortable.

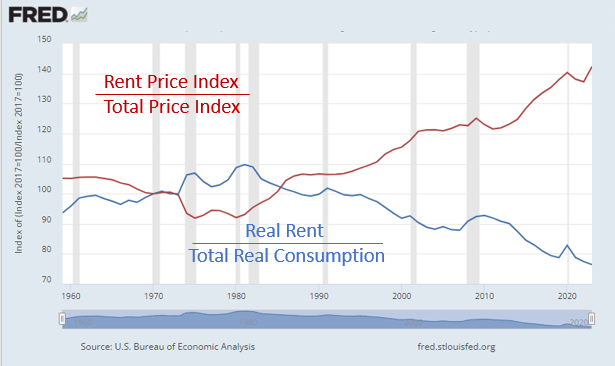

So, before the 1980s, there seems to have been a negative relationship between rent inflation and the supply of housing, but it basically added up to a stable portion of total spending in any case. Figure 1 compares aggregate housing supply (“Real rent”) and rent inflation (“rent price index”). I used the indexes for the price and quantity of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) for housing in the numerators and the price and quantity of total PCE for the denominators.

Before the 1980s, total spending on housing was relatively stable, and we were building a lot. When local supply constraints started to bind after the downzonings of the 1960s and 1970s, housing supply wasn’t keeping up with American income. This wasn’t a change in demand. If demand had declined, Americans would have been choosing to spend less in total on housing. It was a decline in supply, and when supply is constrained, families spend more for less of it. In these national indexes, each 1% decline in housing has been associated with 2% of rent inflation. The less we get, the more we spend.

I think this is in the range of typical measures of housing demand elasticity. But, this is an aggregate of many households with very different contexts. It is very regressive. The inflation falls the most on families who are trying to hold on to housing necessities. Before 2008, the rise in rent inflation was mostly from regressive rent trends in the Closed Access cities (NYC, LA, San Francisco, Boston). Since 2008, it applies to most cities.

That is regarding rent - the use of housing. Looking at the price of housing, there is another multiplier effect. Land trades at a higher premium than structures do, because structures require maintenance. I estimate that rent inflation fetches a price multiple about triple the price multiple for real rents that reflect the cost of construction. So, as the inflated value of location becomes a larger portion of rent and the base cost of the structures becomes smaller, home price/rent ratios rise.

So, a 1% decline in housing supply might lead to a 2% rise in inflation, which is then associated with something closer to a 6% increase in price.

In Figure 2, I compare an estimate of cumulative residential investment minus depreciation of structures to aggregate residential real estate. The measures line up closely in the post-World War II era when construction was active. Then, just as with rents in Figure 1, they diverge after the 1970s. Cumulative residential investment declines as a percentage of GDP and residential real estate goes the other direction, claiming a larger value relative to GDP. These are loose estimates, but, it does happen to be the case that the divergence between the capital invested (down 20%) and the inflated value (more than 100% above the accumulated capital investment) is roughly 6:1. (And that’s after the significant reduction in market values that are due to the 2008 mortgage crackdown.)

For our purposes here, don’t get too hung up on my precise numbers. For each 1% decline in actual housing, there is a corresponding rise in market values that is multiples of that. This is a level of housing market value that would be practically unattainable in any other way. How do real estate values fluctuate when there is a building boom? They fluctuate like they do in Figure 2 before the 1980s. Very little.

One thing to take away from Figure 2 is that building booms aren’t associated with volatile, rising real estate values. The more correct way to think about it is that when supply is constrained, changes in demand are associated with volatile real estate values. And, cyclical changes in demand are also associated with cyclical changes in new construction.

So, in Figure 2, you can see that the boom of the 2000s was associated with a temporary pause in the long-term decline of the American housing stock, but the accumulation of residential investment just doesn’t move the needle much on real total real estate value. The rise in home prices and the rise in construction in the 2000s both were due to higher demand. But it is completely misconstruing the period to say that a building boom caused real estate values to be so high.

Demand with constrained supply caused values to be so high.

There is a common refrain that “we weren’t as wealthy as we thought we were”. The idea is that Americans were constructing too many homes in the 2000s because their inflated prices convinced us we could afford more. And, the apparent solution to that problem was to take a billy club to the American homebuilding and mortgage industries to force us to act as poor as we were.

But the elevated values are due to inelastic demand. We are spending more because we have less. Building more housing is the only way to lower our spending on housing until it matches our economic condition! We were spending too much on housing services and we needed to invest more in houses to fix it. It’s the only sustainable way to fix it. Since 2008, we have increased what we spend on housing services. We made sure that we would have less, and as a result we spend more. We are poorer than we should be. That poverty is capitalized into the elevated prices of our homes. The poorer we make ourselves the richer our real estate will be.

Figure 3 compares annual residential investment to aggregate residential real estate value over time. The sustainable level of net residential investment is probably around 2%, so in the 1960s and 1970s it was declining, but it still represented abundant supply. Americans were consuming more housing, and at times total value moderately increased along with that. That 2% threshold was crossed around 1980, and we have rarely had enough residential investment in a given year to stabilize rents since then.

In Figure 4, I detrend each of the measures from Figure 3. This is mixing levels (real estate values) and flows (net residential investment), so don’t try to make too much of an association between the actual slope of the lines here. As shown in Figure 2, the change in the level of accumulated residential investment is very slow moving.

Looking at it this way helps to see the cyclical correlations. We have 2 correlations at cross-purposes. Secularly, low residential investment is associated with rising home values. But cyclically, increased residential investment is associated with rising home values.

The price boom from 1997 to 2006 was so strong because both correlations were associated with higher prices - cyclical demand was high and secular supply was low. And this is an important place where an honest reckoning with the importance of supply should upend your notion of what the appropriate policy response should have been - and should be going forward from today.

As I touched on in the previous post, the 2006-2007 period is important in this regard.

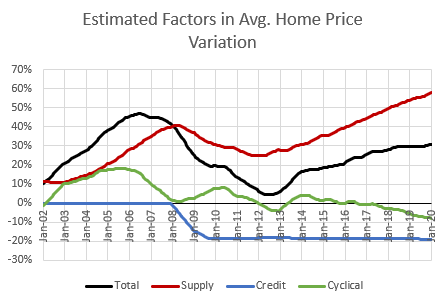

Figure 5 shows the disaggregated elements of American residential real estate. (1) the cyclical element associated with fluctuations in demand, (2) the supply element associated with the secular shortfall of supply, and (3) the one-time credit shock that was imposed after 2007.

The end of 2005 was the top of the cycle. It’s the peak of both residential investment and cyclical home price appreciation in Figure 4. It is the peak of the aligned correlations - both the supply shortage and the demand spike were pushing prices up.

Now, at that time, this was very regional. Most places didn’t have particularly high price appreciation or construction activity. So, the supply-related price appreciation was largely in the Closed Access cities. The cyclical spike was mostly in the sand states, who were taking in all the extra demand for housing that wasn’t being met in the Closed Access cities, including the large number of housing refugees from the Closed Access cities.

Since the market was universally treated as solely a hot cycle, the policy choices were all toward killing the cycle, and in 2006-2007, we did. By the end of 2007, the cyclical impulse was back to neutral. But total residential real estate values remained high through most of 2007 because ending the demand cycle meant ending the building boom. As I pointed out in “Building from the Ground Up”, the Fed was explicit during that period that their goal was to end the building boom. (Although, initially, they forecast a bottom in housing starts that was still pretty high. If only they had adjusted their monetary policy to hit their 2006 forecasts. As the forecasts declined, they just became more pessimistic along with them.)

Until 2005, the 2 housing forces were both pushing prices up. In 2006-2007, the cyclical forces were pushing them down and the secular forces were pushing them up, leading to a price stalemate. Prices remained level.

Then, the mortgage crackdown caused all hell to break loose. It’s hard to know how 2008 would have gone without the mortgage crackdown. Maybe just avoiding that one catastrophic error would have prevented 80% of the damage that ensued.

But, the point I am trying to make here is that the right policy choices in 2006-2007 are clear as a bell, in hindsight. We needed a building boom. We needed the opposite of what we had. To sustainably moderate home prices after 2005, we needed a building boom.

The stalemate in 2006-2007 was from a continuing supply shortage and a declining cycle. The stalemate we needed was a continuing cyclical boom and a reversal of the supply shortage. Figure 6 suggests what that would have looked like.

This is where brains explode when I suggest such a thing. To those plurality of supply skeptics that think the 2000s housing market was a demand bubble, full stop, the idea that we should have attempted to stabilize housing starts as soon as they started to decline is deep, utter madness. “We needed to be disciplined!” they insist. “If you let those cyclical risk-takers off the hook, then the next cycle will be even worse! You would just let all those borrowers in 2006-2007 who had refinanced their mortgages on overvalued collateral get away with it?!” They think I’m dangerous.

By late 2007, again, in hindsight, it was clearly appropriate to expect construction to recover. The Fed didn’t aim for that, and instead, we imposed the late shock on prime mortgage lending that turned the correction into a crisis.

Look. The market through 2005 was too hot. It shouldn’t have been too hot. It was too hot because our supply conditions are so bad. And, so, when residential investment was just barely running at a sustainably high pace, it created massive dislocation. Hundreds of thousands of households had to be displaced from the Closed Access cities because housing demand was rising faster than those cities can grow. The way that displacement happens is Closed Access rents and prices rise high enough to make remaining too painful for someone.

In 2004 and 2005 there were enough of those Closed Access refugees to overwhelm Florida, Arizona, and Nevada. That market was too hot for our pitiful housing market. If we insist on binding our proverbial housing feet, we can hardly expect to sustain a brisk jog. So, cooling off from 2005 was reasonable. But that’s it.

By early 2006, the cycle had started to decline. By 2007, migration into the Contagion cities in Arizona, Florida, and Nevada was in deep decline. The optimal policy target by late 2006 was to put the monetary policy pedal to the floor until starts stabilized, and frankly until the poor residents of NYC, LA, San Francisco, and Boston started hurting again, but hurting just enough to form a gentle river to Arizona rather than a gusher that would overwhelm Arizona’s willingness to build homes.

Don’t get me wrong. That’s not remotely what I would choose. I would build homes in LA. But I can’t. A sustainable rise in housing supply requires painful displacement from the stagnant cities.

Let me ask you a question. If our problem is the secular supply constraint, then how do we reverse that? How do we ever get home prices to go down again?

Any reversal of the secular decline will, inevitably, look like a cycle that isn’t being corrected. The supply skeptics who think everything is a cycle will actively block any transition to housing abundance. If the secular trend ever turns up, they will kill what they think is a cyclical bubble.

And, guess what?! According to the Erdmann Housing Tracker, we are at a prime moment. The supply component has been relatively flat, post-Covid. There was a brief cyclical bulge that has now corrected and is roughly neutral. We are now at a 2007 moment where we could let a cycle run hot until it becomes the secular reversal.

Housing supply is currently temporarily supply constrained. Once supply chain constraints are worked out, builders may be primed to grow 10% to 20% annually. They could do that for years on end. And, to utilize that new capacity, it probably wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world to let a cycle run a bit hot.

A hot cycle and a recovering supply constraint should be relatively neutral. The cycle would be inflationary and the loosening of supply constraints would be deflationary. But, already, there are many loud voices calling for a downturn. We actually have a chance to reverse the secular supply downtrend. But, who will be willing to let the market run when it looks like a hot cycle? Especially when the excess value from the supply problem itself is widely mistaken for cyclical excess or monetary stimulus.

It’s the only way. Doing the thing that will cause everyone to lose their heads is the only way. If the downtrend in those supply charts ever turns up, it will look like cycle. It will be a cycle. It will be up to us to make it permanent and turn it into a secular shift. How can we possibly succeed at something that so many passionately will oppose for a hundred different reasons?

Kevin, your analysis is always impressive but the one variable that you don’t discuss is the impact of demographics on the mix of housing types in demand. Baby Boomers like me are just now reaching the age where “aging in place” is no longer practical, but downsizing to single level living puts us in direct competition with our millennial children who are looking for starter homes for their new families.