Housing under constraints

The gears turned by supply deprivation

One reason housing is difficult to think about is that “housing” includes a number of bundled components which each suggest a different supply and demand context. Housing includes basic shelter from the elements, a centerpiece for entertaining friends and displaying a lifestyle, the infrastructure for basic daily needs or more luxurious versions of that infrastructure, proximity to neighbors, friends, schools, jobs, general safety (or lack thereof), and on and on.

Components of housing exist all along the diamonds vs. water axis. In some contexts, marginal additional consumption of housing is similar to choosing between the solitaire diamond ring vs a gemstone setting. In other contexts, it’s like the negotiation between the nomad crawling out of the desert and the trader with a bottle of water. And, these different demand elasticities are clear to see across the American housing landscape (comparing, say, a 9,000 square foot mansion in suburban Houston - a solitaire ring - to an unpermitted backyard unit in an immigrant enclave in Los Angeles - a bottle of water for a thirsty nomad).

Supply elasticity also varies greatly across the country. As I argued in an earlier post, really housing supply follows a similar pattern in every metropolitan area. The supply line in any given metro area is basically shaped like a tangent curve. Vertical at the left, where the existing stock of homes basically serves as a fixed lower bound on the quantity of homes available. Then, at some low rate of growth, supply is very elastic. Then, at some higher rate of growth, which is different for each metro area, the willingness of the region to process and approve new units maxes out, and supply goes vertical again.

This is also easy to see across the American landscape, where you have cities like Cleveland that are at the left end of the supply curve, where you can own some homes for little more than the cost to maintain them, and some cities at the right end of the supply curve, where higher prices can’t trigger significant new supply and so prices and rents are almost entirely the product of shifts in demand. Then there are a lot of cities on the elastic part of the curve. Where this is evident (or at least it was evident before we broke the American housing market in 2008), is by comparing, say Kansas City to Atlanta to Nashville to Birmingham. Those cities might have annual growth rates of 1% or 2% or 3% over the course of a few decades. It doesn’t affect relative values much.

If you chart long term home price appreciation against population growth (Figure 1) or median Price/Income against population growth (Figure 2), it is easy to see this dynamic, and it is easy to see which cities are where on the supply/demand diagram.

To be one of the cities on the far right end of Figure 1 & 2, there has to be high demand for living there, and you have to have generous building regulations (i.e. the supply curve in Figure 3 has a right maximum limit well to the right). It would be next to impossible for a city willing to approve ample building to move well above or below the narrow range of moderate home price growth over the long term. (Agglomeration economies accrue to value and consumer surplus, more than to price. Only exclusion accrues to price.)

So, in Figure 1 & 2, there are a large number of cities (1) that fall somewhere along a very flat (elastic) supply curve. There are some number of cities (2) where the natural growth rate is higher than the short-run supply maximum. Notice that none of those cities (as shown in Figure 1 & 2) has an especially high growth rate. In other words, high housing costs are never driven by growth. They are always driven by deprivation. As I’ve said before, calling expensive cities “superstar cities” is giving them way too much credit. As far as anyone knows, if LA let itself grow as fast as Kansas City, it would be as affordable as Kansas City. In fact, back when it did, it was.

Then there are a handful of cities (3) where slow growth or decline has pushed demand down to the inelastic left-hand side of the supply curve and homes are especially inexpensive. And occasionally, but only temporarily, demand pushes some high growth cities into short term inelastic supply and rising prices. Several cities are experiencing some version of that today, although, almost universally, they are hitting that condition at much lower growth rates than they did before 2008. (Supply has gotten squished left almost everywhere.)

But, all of these “average” and “median” metro area numbers actually hide most of what is interesting. Here are price/income ratios for ZIP codes in 2002 Phoenix (a quintessential elastic supply city) and 2021 Los Angeles (a quintessential inelastic supply city). I have highlighted LA and Phoenix in Figure 2.

Notice that 2002 Phoenix has relatively equal price/income ratios across the metro area. That is what elastic supply looks like! When supply is elastic, there is no water vs. diamonds paradox! Families mostly just spend what is comfortable for the parts of the “housing” bundle that are necessities, and upgrade to the luxury parts of the bundle as their incomes permit. There is much more to say about this, which I will leave for future posts.

In this post, I just want to leave you with the thought that that sloped price/income line in Los Angeles is a picture of the irregular elasticity of demand for housing - this natural mixture of necessity and luxury. Where supply is constrained, families of means simply economize on the luxury component of housing, mostly by trading down into units that, in Phoenix, would be inhabited by families with lower incomes. As you move down the income ladder in a supply constrained city, housing becomes more of a necessity good, demand becomes more inelastic, and so prices are driven higher. At the lowest extremes, it becomes quite like the bottle of water for the desert nomad.

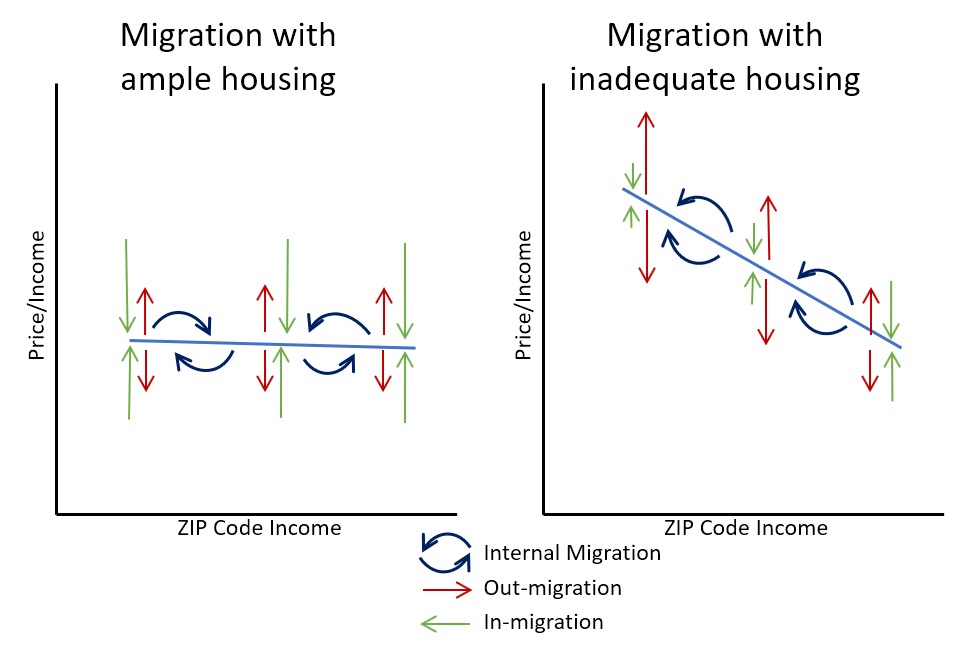

Finally, the last figure here highlights how that works. In 2002 Phoenix (which is representative of the left panel), there is ample housing for all, and the city is full of idiosyncratic transactions. Families trading up or down, neighborhoods rising or falling in favor, etc. It is a glorious mess, full of its share of winners and losers, but, on net, undoubtedly, mostly winners.

In LA, that mess becomes increasingly systematic. Every housing decision becomes an exercise in compromise. Every transaction or migration across socio-economic sub-tiers becomes a process of poaching supply from the lower tiers in order to economize on luxuries. The demand for high tier homes claims supply that would have met low tier demand. Those pressures build systematically, and linearly, downward through a city’s population, scaling up the discomfort at each turn. Some families at the top of the income spectrum might choose to migrate away with the smallest amount of discomfort. But, as the pressure mounts on families with lower incomes and fewer options, the discomfort required to dislodge them from a home full of necessities (family, job, friends, social safety net) rises until they suffer a level of housing costs that many people would consider inhumane. (In fact, many did, and they already moved away as price/income levels rose past 7, 8, or 9, to whatever level was associated with the discomfort needed to dislodge them and create space for another family in a city that won’t build for them.)

Your graph comparing LA and Phoenix made me wonder about the potential negative impacts on traffic networks caused by inelastic housing markets. Does a high price/low housing supply city result in more congestion because low income workers have to travel further from lower cost ring neighborhoods? My 5 second Google research showed Phoenix as having a lower average one way commute than Los Angeles. I'm willing to bet that income effects exacerbate that. A white collar WFH person in Southern California could have a daily commute time of zero, but his landscaper could have a 90 minute one way trip in the morning and afternoon.