With prawns like these, who needs anemones?

Carol Roth, the author of “You Will Own Nothing: Your War with a New Financial World Order and How to Fight Back” has an op-ed at Fox News titled, “Five ways the Trump administration can save the American Dream and prevent socialism: Home ownership shouldn’t feel out of reach for young Americans”

She begins by noting that young adults are being turned against capitalism and toward socialism because of the rising cost of living - especially the rising cost of housing. But it is cronyism and regulation that have made housing expensive.

That sounds promising! Like a potential ally in housing access. But, unfortunately, this is a good example of how blind-spots among conservative economists and pundits put them on the wrong side of many of the most important policy debates regarding housing. Those blind-spots mean that there is not a large coherent pro-market commentariat for housing in America.

She has several suggestions to fix the housing problem as she sees it.

Lower mortgage rates through more assumable loans

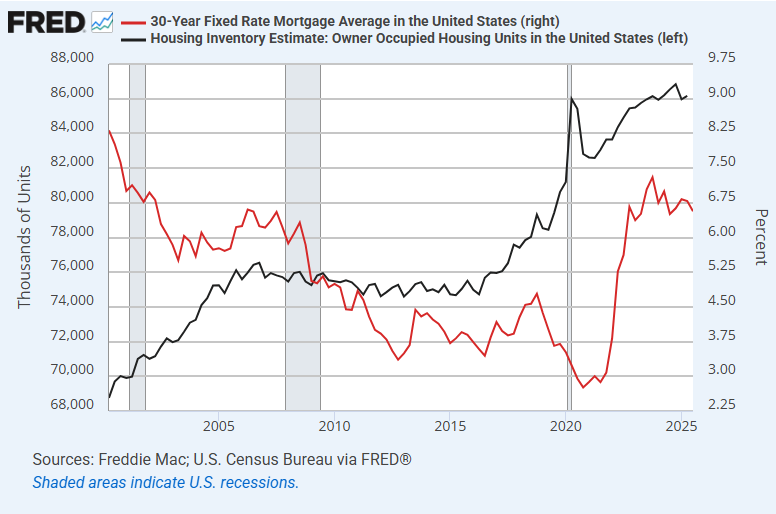

There isn’t necessarily anything wrong with this policy suggestion, but the problem here is what wasn’t said. Figure 1 shows owner-occupied homes and mortgage rates. How many homeowners would there be if we had assumable loans? Maybe 87 million instead of 86 million?

In 2006, there were 76 million homeowners. In 2016, there were 75 million. How many homeowners would there have been in 2016 if mortgages were assumable?

I think there is a sneakily unhelpful intuition among right-leaning pundits. It is a naturally conservative intuition to think that everything is too expensive all the time. Other people pay too much. Speculators are pro-cyclical. The government stimulates demand and blocks supply. The Fed creates too much inflation. In terms of personality, all of these are biases that will inevitably accumulate among conservative-minded people.

And, so, when the government puts a straightjacket on private lenders, it apparently is just too much of a stretch for someone who has been building a worldview with those intuitions to see it. So much for the friends of capitalism. Of course, this gets all wrapped up in the complicated topic of how involved the government should be in mortgage access through its mortgage agencies and how generous or punitive the government should be toward financial institutions during economic upheavals when debt contracts become stressed, so it is difficult to have a conversation about private lending regulations without being overwhelmed by the baggage of the broader picture.

A multi-sigma shift in lending standards was imposed by the federal government in 2008, and conservative-minded pundits and economists simply can’t see it.

Nationwide, in 2005, mortgages worth more than 2% of the total market value of owner-occupied real estate were originated to borrowers with credit scores below 760. About 0.7% of real estate market value was originated to borrowers with scores above 760. These proportions were not substantially different than they had been for years, if not decades.

In 2008, lending to scores under 760 dropped to 1% of total owner-occupied real estate value (which is actually an inflated number because the market value of the real estate had temporarily collapsed). Today, mortgages to scores above 760 are nearly at the pre-2008 norm. Mortgages to scores under 760 are now down to 0.3%!

In 2015, homes were cheap and interest rates were low, and yet the number of homeowners was less than it had been a decade prior. In both 2005 and 2015, homes across Dallas, for instance, could be purchased for between 2.5x and 3x their residents’ reported incomes.

High interest rates and high home prices are definitely not the reason that homeownership became more difficult. I’m afraid we are divided between those who can see this and those who simply cannot.

Create incentives for smaller footprint housing

Roth’s second policy suggestion is incentives for smaller homes.

Of course, the reason builders stopped building smaller homes was because the federal government wouldn’t let their potential buyers get mortgages.

Lacking the possibility of considering the real reason, Roth writes, “Why would a homebuilder choose to build a smaller home when they could make a bigger profit on a larger one for an incremental amount of extra work? This is where tax incentives, both locally and federally, could help prompt builders to build smaller footprint housing that would also be more affordable, particularly for young people.”

I don’t know what Roth’s position is on the pre-2008 building boom. Why does she think builders built more than 500,000 homes selling for less than $300,000 each year back then? Why does she think they abruptly stopped? Did tax incentives change?

Also, she cites Census Bureau data on the sizes of new homes, which suggests that she looked at the data. This is data that I see referenced frequently, usually to claim that housing supply isn’t a problem. Usually, it’s presented as a sort of “Kids don’t know how good they’ve got it these days.” point.

The problem is that the narrative hasn’t been true for years. She cites the Census estimates of house sizes in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, and then jumps ahead to compare those to today.

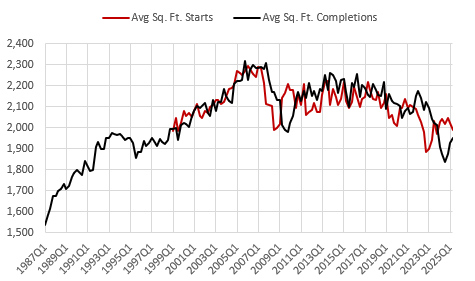

Here’s what happened to new home sizes since the 1970s. The average new home size is no larger than it was 30 years ago, and its been shrinking since 2008.

By the way, a little Easter egg in Figure 3 for the real Erdmann Housing Tracker geeks: That big sudden drop in average home size of starts began to drop in 2006 and bottomed out in the 3rd quarter of 2008. It happened before the financial crisis. Why? Because the mortgage crackdown killed the single-family housing market, but apartment starts were strong, right up until the September crisis. The initial sharp decline in average home size was due to a compositional shift as single-family housing starts collapsed.

Figure 4 compares average home size for single-family and multi-family units. They both rose proportionately from the 1980s to 2008. You might wonder why. Weren’t homes becoming unaffordable in the 2000s?

Yes. They were - regionally - mostly in regions where supply is politically blocked. New homes can only be built where they are allowed to be, and where they are allowed to be, they are affordable, regardless of tax incentives, mortgage assumability, etc.

After 2008, due to the mutual strangulation of mortgage access and local opposition to apartments, homes could not be built in reasonable quantities in most cities across the country. At first, that meant that apartment sizes and single-family home sizes diverged. Buyers of smaller homes couldn’t get approved for mortgages any more - something you’d think would distress a person concerned with access to ownership. So, the average new home temporarily became larger because the market for smaller single-family homes was killed by the mortgage crackdown.

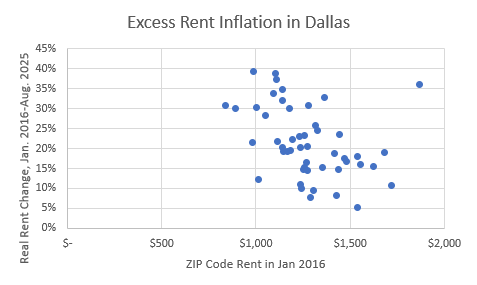

That led to regressive rent inflation. In Dallas, for instance, rents, adjusted for inflation have been relatively moderate in the most expensive ZIP codes, but have routinely risen by 30% or more in the previously cheapest ZIP codes.

Today, in the poorest parts of Dallas, homes now cost 5x their residents’ incomes, while homes in the richest parts of Dallas still sell for about 3x. Why? Because of the rent inflation. And the rent inflation is caused by elevated land values. Land values are elevated because of the collapse in new home construction.

(edit: Goodness. I should have proofread this a couple more times before I posted it. The logic in that paragraph may seem confusing to new readers. The mortgage crackdown collapsed housing construction. Then, hysteresis and production shocks related to Covid prevented it from recovering fast enough to prevent rents and prices from overshooting. It is more straightforward to say that inadequate construction caused rents and prices to rise, and that is why land values are elevated. If builders can build a home for $200,000 that can sell for $300,000 because its rental value is elevated by inadequate supply conditions, they will bid up the lot that house will sit on to $100,000.)

So, by 2016, across the board, in Dallas, and in most other growing cities, new home buyers - of both single-family and multi-family units - started reducing the size of the homes they were buying because more of their total expense had to go to the land.

The real Case-Shiller home price index is up 32% since the beginning of 2016. The size of the average new single-family home is down 11%.

Roth wrote, “One of the reasons that housing is so expensive is that we have had square footage creep.” The numbers in the article that follow that statement are all true. There was square footage creep in 1970. The statement accompanying those numbers is fundamentally false. There was square footage creep when homes were not expensive. Now that they are expensive in most cities, homes are getting smaller. She had to have seen this when she looked at the numbers. I don’t think she was trying to be misleading. I think, when the most important fact is invisible to you, it is hard to see facts clearly - like a shaman trying to stop the spread of a pathogen. She’s doing the best that she can.

Will the average new home size have to devolve back to the average size of new homes in 1970 for this talking point finally go away?

Address rising property taxes and insurance

She suggests lowering property taxes.

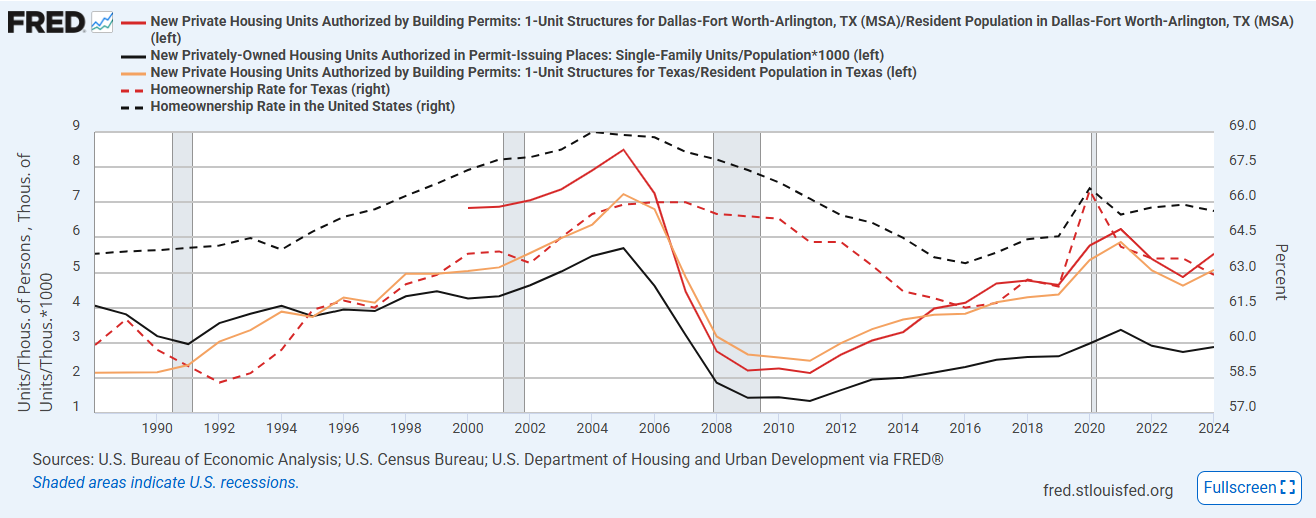

Let’s look at Dallas again. Texas is known for its high property tax rates. Figure 6 compares single-family home construction per capita in Dallas and Texas to construction across the country (solid lines) and homeownership rates in Texas and across the country (dashed lines). Dallas and Texas are in red. It is true that the homeownership rate is slightly lower in Texas. Texas has property tax rates that are above average. Maybe that lowers homeownership a bit. On the other hand, single-family construction has recovered more in Dallas and Texas.

Since homes are more expensive because the land under them has become inflated, lower property taxes are an odd choice if affordability is the goal. Higher property taxes tend to reduce land value where land value is elevated.

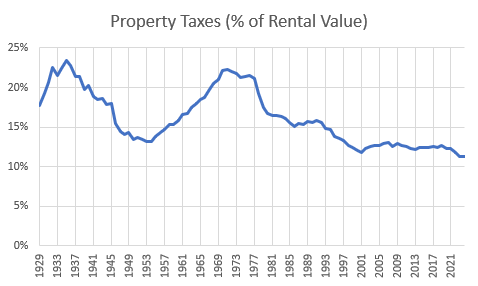

According to BEA NIPA table 7.4.5, property taxes, as a percentage of gross rental value, have declined by half since the 1970s. Prices are high because rents are high. Rent affordability has never been worse. And property taxes have never been a lower portion of rents.

Property taxes are already much lower than they used to be, and rents and prices - especially on the land under homes - have skyrocketed anyway.

(edit: Upon re-reading this, I should have been more clear. On average, lower property taxes should lower rents and raise prices, all else equal, but it could be the case that the typical home buyer would have lower costs after accounting for the change in price and taxes. Rising prices have been mostly driven by rising rents, so high property taxes haven’t been a motivating factor in making housing more costly. But, it is possible that lower taxes would be associated with a small rise in ownership. It is also possible that it would not, since, on average, it would also make renting more affordable.)

Address corporations buying single family homes

Of course, you knew this was coming. From the article (italics mine):

Before 2010, there was effectively no institutional money buying single-family homes. But, in Q1 2025, nearly 27% of single-family homes purchased were bought by investors, with some portion of that being institutional buyers.

Many of the institutionally-backed companies convert single-family homes they purchase to rental properties, taking those dwellings out of the buyable supply and renting Americans back a shadow of the American Dream.

While I hate central planning and prefer free markets, there has been nothing free market about the advantages that give these companies the ability to get cheap capital and go in and compete for single-family homes. Additional fees, taxes or limitations, at least until the market is normalized, could be a good way to level the playing field for average Americans.

Oof.

On the italicized sentences, did big companies only attain these advantages after 2010? What kept them out of the single-family housing market before?

The reason they weren’t in the single-family market before 2010 is because families with access to mortgage credit have and will always be willing to outbid corporations for single-family homes. Corporations didn’t gain an advantage after 2008. Families were put at a disadvantage by overzealous regulation. And, as a result, Ms. “I hate central planning and prefer free markets” says we must add “additional fees, taxes or limitations” on the investors who have come in to the market where families have been stopped.

On the statistic about purchases by investors, the large institutions have not bought many homes, on net, for a decade. Last quarter, they were net sellers. Gross numbers are frequently reported and not very informative. “Some portion” is also not very informative.

Finally, she complains that the investors convert owner-occupied homes to rentals.

Yes. Renters need homes too. We can build more. If the market was less regulated for apartments, investors would build more apartments, and if the market for mortgages was less regulated, those tenants would be homeowners.

And, where homebuilders do build more, it is very clear who pays more for homes. Builders aren’t at a loss for homes to sell to families because corporations keep buying up all their inventory. Builders sell to families, and when sales are slow, they may make a bulk sale to investors at a discount. It doesn’t go the other way. This isn’t hard to see. Rising prices are always associated with rising homeownership.

Oh, and, by the way, as Erdmann Housing Tracker readers know, in Dallas, as in most cities, even at today’s mortgage rates, the homes whose buyers are most sensitive to affordability tend to pay rent that is higher than what the likely mortgage payment would be for a conventional buyer.

Large institutions that own less than a million homes because they generally bought those homes at a discount are not, by any stretch of imagination, the reason that home prices are elevated. And, as long as millions of families are locked out of mortgage access and millions of apartments are legally obstructed by municipalities, those large institutional home buyers are probably the only buyers capable of funding continued increase in new home construction, which is the only way that elevated housing costs will be reversed.

This is the position of self-identified free market advocates, ladies and gentlemen. They are joining Progressives at the end of the political horseshoe to centrally plan who should and shouldn’t build new homes. And, so, unfettered housing markets - the thing we need more of - will have to be won, over their objection, by young families who are in the thick of it and who are the victims of their odd political alliance (in practice, if not in rhetoric).

PS: Follow up post.

Really enjoyed this one! I've always thought that the most compelling part of your thesis is the argument that the government killed demand by cracking down on mortgages, and this piece put that concept front and center.

I work in real estate development in Cambridge, MA, and the city has begun to focus a lot more on trying to expand the housing supply to bring prices under control. I've found it useful to keep your posts in mind as I navigate the local ecosystem - keep it up!

I don't know why housing is so hard to understand, even for economists who should know better.

Maybe a parallel is the topic of education. Everyone knows the four-year college (grad schools may be worse, outside of hard sciences) idea is not working...but academia is on the gravy train...so...

How many academics say something like "Probably two-thirds of college students don't need to be there. Many grad school programs should be folded into a four-year degree. We need to create high-prestige two-year programs in technical and mechanical skills."

But...elites and better-off academics own housing. Wipe out property zoning and let it rip?

A condo with ground-floor retail in your SFD neighborhood?

The real answer is to build more housing, build way more housing, and then build even more. Zone for unlimited housing density across whole metropolitan areas. If you want to subsidize housing, give $10,000 or $20,000 to developers for every unit completed and sold.

And remember, all new housing is affordable housing. A new luxury unit means someone moves into that one, opening up another home, perhaps for middle-income buyers, and so on.

You know what happens when there is too much supply? Rents go down. See downtown Los Angeles office markets.