Over at Marginal Revolution, Tyler Cowen has a couple of recent posts on this point.

It started with a link to the “Antiplanner”, arguing that the prevalence of high rise apartments in South Korea is an important reason for their recent sharp declines in fertility.

Marginal Revolution commenter “Sure” built on the Antiplanner’s point and pushed back against the common agglomeration story. “Sure” argued that broad upzoning would lead to movement out into the suburbs rather than into the urban cores. People want space and a short commute. “YIMBY will end up resulting less in skyscrapering the cities and more in multiplexing the burbs.”

Will Rinehart responded to “Sure”:

Sure is right that “If we liberalize zoning everywhere (i.e. the YIMBY dream) then we should expect a net movement from the areas where people say they don’t want to live to the areas where they say they want to live.” But they misstep in thinking that “on net that means out of the urban core and into something less dense.” In the open-city Rosen-Roback model, generally speaking, liberalization of housing would mean people head into the urban core and into the suburbs.

In total, Sure seriously overweights commuting time and housing space, and underweights education as an amenity and local consumption.”

Basically, Rinehart is making a case for amenities. Unencumbered demand will flow to where there are amenities. And he argues that schools and local access to goods and services are more important than space. That settles at an equilibrium where people tend to agglomerate into more dense urban distributions when given the opportunity.

You might put it something like this: Poor households prefer density. All households prefer to live near rich households. Where population is dense, households especially prefer to live near rich households.

Model that!

Some Earlier Posts

I think my work might add some nuance here. Some previous posts are:

“The higher costs don’t come from positive demand. There is positive demand in Austin. The excess costs come from inertia. They come from the preference not to be displaced. They come from the value of locality and community which the non-cosmopolitan locals value, and which prevents them from moving away from cities that are committed to non-growth… Cosmopolitanism isn’t the cause of high housing costs. Quite the opposite.”

Here, I discussed the four main things that households are buying in urban housing.

Shelter

Neighborhood Amenities

Metropolitan Area Scarcity

Endowments

The main reason that some cities from the first post are more expensive is the fourth category: endowments. Those cities require outmigration, and families choose to pay very high costs to avoid regional displacement.

Here, I discussed how a given home can behave like an inferior good, a necessity good, and a luxury good, depending on which of those demands it is filling. This makes modelling housing demand challenging.

One tricky aspect of trying to understand urban housing demand is that density appears to have value, but it is an inferior good. It mostly adds value for households with lower incomes.

There are several points arising from this that I would add to the discussion. In the end, I think these points basically support the points of “Sure” and Will Rinehart, but in ways that are a bit complicated.

Cities are expensive because of obstructed building, not excess demand.

The first point is that, for the most part, the expensive cities (the “Closed Access” cities, in my parlance) aren’t expensive because they are “superstars”. They are expensive because they don’t build housing.

Figure 1 highlights this issue. Here, the blue bars reflect actual population growth and the gray bars reflect the amount of regional displacement (financially motivated domestic outmigration) that was associated with rising housing costs, from 2001 to 2019.

The metro areas are ordered according to the amount of regional dislocation. That is the main factor associated with high costs. Think of the sum of the blue and gray bars as the total demand for population growth in a city. It isn’t that high in the expensive cities. What makes them different is that they permitted so little housing. What makes them expensive isn’t that a lot of households moved in. It’s that when households did move in, someone else had to move out. Their net growth is generally abysmally low.

In other words, the idea that New York, LA or San Francisco are expensive because of job growth, high incomes, productivity, amenities, or the value of density is not substantiated. One of those metro areas would need to permit as many houses as San Antonio for a few years to confirm such claims. They aren’t even close. And, until that happens, you must consider that if demand is the primary driver of these high costs, it is a doozy of a coincidence that all of the most expensive cities just happen to be the slowest growing metro areas with the lowest rate of housing permit issuance in the country.

Figure 1 is actually an understatement, because the post-Great Recession mortgage crackdown has had a regressive effect, causing housing construction to decline the most in the cheapest cities. Before the Great Recession, the expensive “Closed Access” cities were firmly at the bottom of the list in terms of housing permits and population growth, below all of the major Rust Belt cities.

So, my point is that if there was broad upzoning, the expensive cities would definitely grow, but the demand for living there might not be as high as it is commonly assumed to be. To the extent that those cities are dense, there is no evidence that they have been overcome with a tremendous wave of demand. They would have to attempt to accommodate growth to create that evidence.

Density is correlated with higher expenses mostly because it is associated with NIMBYism.

Second, it isn’t necessarily the density that makes the expensive cities valuable. This may be a spurious correlation.

It is NIMBY politics that determines how many homes a city permits. It is the low permitting rates that make these cities different. It is easy to claim they are special. It is plausible. But, it is objectively definitively true that they permit new homes at much lower rates than other major metropolitan areas. Specialness is a claim. Low permits is a fact.

NIMBYism is correlated with density. Under our current municipal governance models, the more dense the area is, the more objectors there are to show up to the city council meeting to complain about new developments.

For the most part, density doesn’t make New York City and San Francisco more expensive because it is valuable. It makes them more expensive because it lowers the permitting rate. Density, with today’s governance, is associated with less supply. It’s hard to know how much it is associated with more demand.

Again, if you are skeptical of this point, then you have run into one of the most unfortunate coincidences of modern economics. The most valuable places in the country just happen to have population and migration patterns similar to economically failing regions.

It isn’t a coincidence at all, of course. The planning department in New York City isn’t begging developers to put up new high rise apartments, only to have them reply that the bedrock under Manhattan just can’t support it, or the construction costs just don’t support it. To the contrary, developers are begging planning departments to let them build, and the planning departments reply with years of complaints about shadows, high incomes of new residents, low incomes of new residents, crime, gentrification, etc.

That is one spot where I think “Sure” smuggled in one of the errors of conventional wisdom. They wrote, “Outside of a handful of cities with extremely harsh geographic constraints (e.g. NYC, SF), upzoning the burbs will likely eat into the city cores more than new folks will move to the city cores.”

Extremely harsh geographic constraints? I’m not sure that even requires much commentary. I think the fact that someone could write that about New York City (I’ll leave San Francisco aside, here, though we could debate even that.) with a straight face is good evidence of just how strong our communal intuition is to give these cities the benefit of the doubt - to see the clear evidence of their failures and ascribe it to a state of nature or to their supposed superiority.

The only thing keeping anything from getting built in New York City is a web of self-imposed caps on density. If New York City can be described this way, what city couldn’t be? You could say that the sunbelt cities aren’t constrained because they are still surrounded by undeveloped flatlands. If Dallas eventually is entombed within a ring of exurbs full of minimum lot sizes measured in acres, then will we say it has “harsh geographic constraints”?

Home prices in dense existing neighborhoods may be rising more because they are inferior to less dense neighborhoods.

Wait. What?

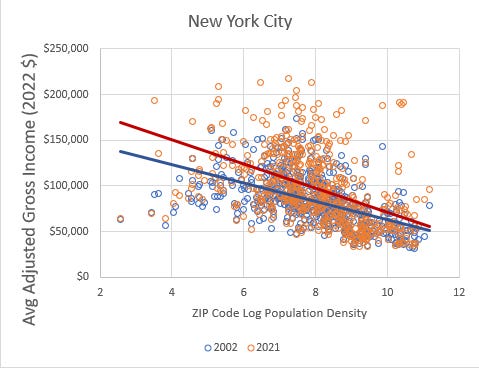

As I noted in one of the earlier posts, there isn’t that strong of a correlation between density and home prices. In New York City, as recently as the 2000s, home values in the densest ZIP codes were lower than home values in less dense ZIP codes (Figure 2).

That is because the densest ZIP codes are quite strongly associated with lower incomes (Figure 3).

Households in dense ZIP codes spend more of their incomes on housing (Figure 4). But, that is mostly because they have lower incomes!

Now, it is clear that denser areas have amenities that can net out to a positive. Clearly, in almost every metropolitan area, as you move in to the metro core, you will tend to give up lot size and unit size in exchange for access to commercial and cultural amenities, transportation options, etc. But, the complication is that poorer households tend to make more of a tradeoff for more density than richer households do.

As Figure 5 shows, in every city where home prices have increased excessively, it is highly correlated with incomes. In cities that lack adequate housing, demand for living in the metropolitan area creates a premium that applies to every home in the region. This sets in motion a systematic process of households with higher incomes outbidding households with lower incomes. That is the “Metropolitan Area Scarcity” factor listed above.

But the price where that market settles is based on the “Endowments” factor. How excessive do the costs have to be for the current households with lower incomes to choose to be regionally displaced.

In other words, the rising cost of dense parts of New York City may have less to do with the value of density for the new residents than it has to do with the value of density for the dwindling number of existing residents.

You can see that the change in home prices in New York City in Figure 5 is less systematic than in the other cities. In Los Angeles, the relationship between income (on the x-axis) and home prices (on the y-axis) is quite regular. In New York City, there are sort of two different patterns. In the richer parts of the city, prices haven’t changed that much. In the poorer parts of the city, there has been a lot of variance between different ZIP codes.

This requires a complicated statistical review. How much of those rising price/income ratios is due to changes in home prices, expected future changes of the incomes of residents in gentrifying ZIP codes, previous changes in incomes of ZIP codes that have already changed, etc.?

In every city, there is income-sensitive price appreciation because of the bidding war for an inadequate stock of housing (more so in LA than in Houston). New York City is unique in that there also is density-sensitive price appreciation.

But, how much of that density-sensitive price appreciation is related to the value of density and how much is related to the pre-existing condition that dense ZIP codes are where the poor families are, so that is where the bidding war and localized socioeconomic transition is most fierce.

Conclusion

So, I think “Sure” has a point. Maybe, if there was broad-based upzoning, households would move into the suburbs and there would be less pressure on the dense cores. Maybe the prices of the dense cores have been inflated by the lack of options for new housing in the parts of the cities that people would rather live - and, in fact, where richer families live now.

Sure isn’t just stating a presumption about preferences. It really is the case that rich households in New York City tend to live in less dense ZIP codes. New York City may be the only metro area where there is enough diversity of density to even produce clear statistical patterns.

Rinehart also has a point. I suspect that his point is a victim of these complications, too. You might put it something like this: Poor households prefer density. All households prefer to live near rich households. Where population is dense, households especially prefer to live near rich households.

Model that!

I think, if you look at Figure 2, 3 and 4, the most notable changes are that incomes are rising more in the moderately dense ZIP codes while prices are rising more in the densest ZIP codes. That seems to confirm Sure’s intuition.

Maybe a bunch of “missing middle” housing east of Brooklyn and north of the Bronx will relieve the price pressures in the Bronx and Manhattan.

Maybe, all of these loosely related factors are bundled into what we call “housing”. The demand for “living in New York City” has increased the cost families must pay to “stay close to grandma, mass transit, a 20-year employment relationship, and local public support services I am familiar with” and it has been widely misattributed to a “luxury” demand for density which is, in reality, mostly an “inferior” demand.

I have sometimes engaged in an assumption that home prices in the suburbs and exurbs have been inflated by the constraints on core, infill, dense development. I have thought of broad upzoning with a mental model that land would become more valuable in the city cores, and that, roughly, there will be some properties that gain value as they attain the right to hold dense residential housing. There will be other properties in the suburbs and exurbs that will lose a lot of value. They will have the right to build more densely, but not the demand for it.

To me, much of the debate about how aggregate real estate values will be affected by upzoning is basically about where you assume that margin is. On the gradient from core to exurbs, where do lots start to lose value after upzoning.

I have thought, and continue to think, that the aggregate value of real estate in these cities would clearly decline after broad upzoning. I don’t consider the alternative to be plausible, let alone arguable. But, still, there should be some margin where upzoned land at the core has enough development value that its current owners would gain, and the losses would be concentrated in the suburbs.

Sure might have a point. And, I think Rinehart’s point supports Sure’s point. If there was truly broad upzoning, households might choose to move out to the less dense suburbs. They would choose to move to where their neighbors would have high incomes, good schools, etc. Maybe the gradient of added value from upzoning would be much more diffused than I have assumed it would be. In cities like LA and San Francisco, where upzoning should cut aggregate real estate values in half or more, it could be that those losses to the current real estate owners would be broadly shared, and marginal development gains on lot owners that chose to build would mostly only make up for part of those losses.

One easy way to think about this would be thinking about Figure 5. In many cities, housing costs have risen substantially in the past decade, in an income-sensitive way. In Phoenix, for instance, there are depreciating old apartment buildings all over town where real rents have risen by 50% or more - on old units with the same tenants in areas that are already relatively dense by local standards. What would likely happen to those apartments if broad upzoning broad housing costs back down? Those rents would retrace the 50% inflation - probably with the same old units and the same tenants. Meanwhile, in Gilbert, I am surrounded by upper-middle class families who think allocating 11% of the city’s housing to apartments is more than enough, thank you very much. Tons of apartments would fill in Gilbert, and that would lower rents in old parts of Mesa. The high rents on old depreciated units in Mesa aren’t the result of an intense demand from the hoi polloi to live there. Rents are high because that’s where the families losing the bidding war on housing are hanging on to some unit that retains access to local endowments - grandma, social services, etc.

The more I think about it, the more I think Sure is correct and Rinehart’s points mostly support Sure’s main point.

I do think that there will continue to be a growing market for young professionals in downtown Phoenix and Tempe. There is some luxury value in density that cities are rediscovering after spending a century focused on car-centric living in the suburbs. But, that might just be a B-plot happening alongside the much more important plot of housing supply throughout the suburbs.

The thing is, even the more extreme estimates of housing needs, which I ascribe to, of something like 20 million units nationally, would not be particularly noticeable if they were widely disbursed. The odd 8 unit corner lot. An ADU here and there. Fifteen percent of a city devoted to apartments instead of 10%. An extra floor on the 3-level apartment complex.

The urbanist project and the agglomeration story might just turn out not to have that much to do with the more general issue of housing affordability and regional displacement. That doesn’t mean they are unimportant. Building cities that serve us well is still important. But maybe it’s just a different problem.

This brings to mind my revisionist history of the Great Recession. Properly regulating banks is important. We should try to do it right. Reckless lending and speculative borrowing in real estate create problems. We should avoid those problems. A lot of those issues came to a head in the 2000s, and they affected how the 2008 financial crisis played out. But, they really had very little to do with elevated home prices. This should be obvious since we addressed a lot of those problems and homes just returned to getting more expensive again.

Several important things can be happening at once, but that doesn’t mean they are causally related.

There may be some new economic and cultural trends that favor density, but I think you should think two or three times about it before assuming they have that much to do with our housing supply and housing affordability problem. I think even I have been drawn into making too much of a connection between them.

I promise I'll read them.

I get that areas are gentrifying. I'm just having a hard time getting from increased zoning to the new units constructed in those areas will be affordable at the income levels of the existing residents. Hopefully the articles will close that loop.

Austin is a perfect example. This is from census data.

Austin, Texas Change from 2019-2022

Total Households 48,602

Less than $10,000 -2,030

$10,000 to $14,999 1,625

$15,000 to $24,999 -6,615

$25,000 to $34,999 -4,538

$35,000 to $49,999 -4,595

$50,000 to $74,999 6,790

$75,000 to $99,999 7,451

$100,000 to $149,999 6,935

$150,000 to $199,999 12,579

$200,000 or more 31,821

Median income (dollars) $14,002

Mean income (dollars) $21,480

Several years ago Austin allowed accessory dwelling units in what were traditionally lower income areas. The goal was affordable housing which wasn't defined. I've been watching those for several years. Builders are buying houses in those areas, razing the structure, building a larger unit on the front, and a smaller unit in the back which is always the largest unit allowable given setbacks, drainage, etc. Both units are selling for roughly $600+/Ft. The front units are generally about 1400 feet and rear about 1000. Is the rear unit less expensive? Yes, but it is not affordable for the existing lower income residents. It is affordable the additional high-income households.

If you were a builder and given these demographics, what priced house would you build? What would be the safest and most profitable? The builder could have built smaller, less expensive units.

Sorry to be repetitive, but I get stuck on zoning is only housing potential and whether that gets converted to actual housing and its price and form entails many other things.

Today we own several zoned, very expensive multifamily tracts in a very hot area of Austin. We are sitting on them due to construction costs, interest rates, the general economy, and tech layoffs.

I hope I'm not making crazy.

I'm as stunned by house prices as anyone, and I'm positive I don't know all the reasons behind it. I'm really thinking out loud here. It just sounds too simple to blame zoning and leave it at that.

Zoning isn't housing supply. Neither is a 2X4, labor, sheetrock, equity or a construction loan. All of those are only potential supply. After 40 years in residential development, I'm pretty sure zoned land is just a piece of the puzzle to convert those potentials into actual supply, maybe not the most important piece.

When someone says Austin or any other city is unaffordable I keep thinking houses are selling and apartments are renting. Unaffordable units do not sell or rent. Someone bought that $600,000 shack, razed it, and built a $2 million house. It happened which indicates it was affordable. It also happens a lot which indicates there's a market for $2 million houses on single family lots. Maybe it's just the market like a Bentley or a Rolls. Do I wish they were cheaper? Sure, and Bentley wishes they could get more.

I also wonder if using median income to measure affordability in high growth tech cities misses what's going on demographically because it compares past incomes and past purchasing power against current transactions. The longer tenured residents with lower incomes hold back the median income. And, house prices are measured by the most current sale which is usually to higher income residents and are more expensive. Over time demographic change makes the housing appear more affordable. The median income increases as longer tenured residents move.

Crazy stat - Austin is more affordable today than 4 years ago. The median income went up $14,000. :)

Another stat from Austin. The average teacher here makes $57,000. The average tech worker makes $157,000. My gut wonders if this has a bigger impact on the dynamics of housing than zoning.

It's complicated. It can't just be zoning and getting more supply at the right price is a Rubik's Cube.

This is a really interesting subject.