Upside Down CAPM, Part 3: Supply and Demand for Deferred Consumption

In parts 1 and 2, I described a model of capital markets based on a basic observation:

The expected real annual returns on diversified at-risk capital appears to cling pretty strongly to about 6%.

Capital markets are largely composed of two types of capital:

At-risk capital, in the aggregate, has stable expected returns of about 6% plus inflation, but highly variable realized returns. Realized returns are driven by real shocks that change income and expected income, which causes the price of at-risk capital to change until expected returns are again 6%.

Risk-free capital, which has expected returns that change over time, but realized returns are guaranteed to equal expected returns. The savers here are really more of a consumer - a deferred consumer seeking to protect savings to fund future consumption. The borrowers provide that service, and the cost of the service is the difference between risk free fixed income yields and expected returns on at-risk capital. In the conventional models this is called the Equity Risk Premium (ERP) because those models build from the bottom up rather than starting at the returns on at-risk capital and working down. It might make more sense to call it the “fixed return fee” or something.

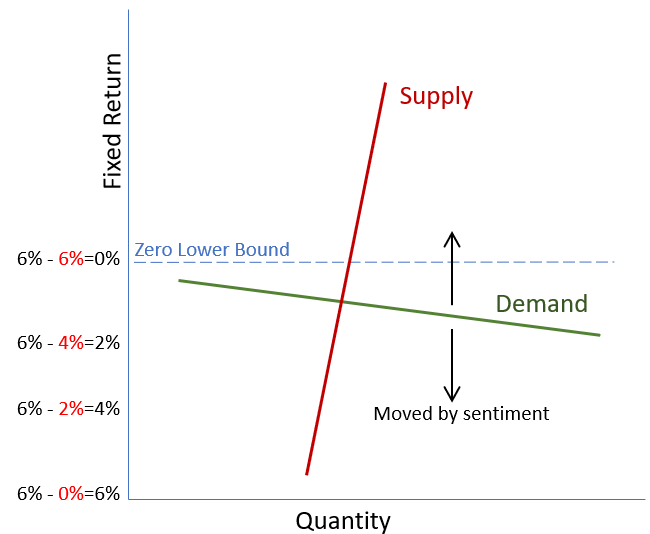

Figure 1 is a supply and demand chart for fixed income (or deferred consumption).

There are several points to walk through here.

Demand for Deferred Consumption

First, the y-axis is a little awkward because this is the “upside-down” CAPM model. The risk free interest rate is what is left after paying the equity risk premium (or the fixed income fee) to get a guaranteed return. So, the “price” is the amount deducted from the stable 6% expected real return on at-risk capital (in red in the figure).

This is why zero doesn’t form an actual bound on risk-free bonds. Zero is just when the fee you have to pay for certainty is 6%. I suspect there is an asymptotic upper bound on real risk free yields in our current economic regime. It will be hard for real risk-free yields to rise above 6%. So, there is probably a cap on real long-term risk free yields, but zero doesn’t form a bottom. There is nothing particularly important about zero when thinking of it this way.

In terms of how the demand curve acts, I’m not going to present a lot of empirical detail here. I would just note that real long-term rates seem mostly moved by cyclical fears, demographics, and general growth expectations. At any point in time, the demand curve for deferred consumption (risk-free debt securities) is relatively flat. Changing supply isn’t going to affect rates that much. This is why real rates were high in the late 1990s when the federal government was running a surplus. Rates were high because growth expectations were high.

The federal government was lowering the supply of deferred consumption (Treasury debt), which probably had a small effect on interest rates, lowering them a bit. But, growth expectations reduced risk aversion and induced investment in at-risk assets instead of risk-free assets, so the equity risk premium was low and real interest rates were high.

The effectiveness of federal spending in raising growth potential likely has more of an effect on interest rates than the increase in federal borrowing does. In other words, more federal borrowing moves the supply curve to the right. Demand for fixed income is inelastic, so that doesn’t change rates much. But, if lower taxes or effective spending improve economic expectations, the demand curve for fixed income moves down. Rates increase as a result. In the 1990s, higher federal receipts and lower federal outlays were associated with improved economic expectations. (I make no assertions here about the complicated causation between those trends.)

Demand is highly elastic (the curve is flat), but highly sensitive to real shocks and long-term changes in sentiment and a financial need for consumption smoothing that move it up and down over time because of other factors unrelated to supply and interest rates.

Supply of Deferred Consumption

Supply of risk-free (or very low risk) assets is inelastic. (The quantity is relatively insensitive to yields. Or, in other words, the supply curve is nearly vertical.) Government bonds are one form of low risk asset, and their quantities can change quite a lot - sometimes in a relatively short period. But, those changes are driven by politics, not changing yields. So, the supply curve can move left and right, but it is steep at any given time.

Corporate Debt

Other low risk securities are basically private debt instruments with ample, secure collateral. Sometimes, that is the production capacity of a mature corporation, usually with a large amount of fixed capital in place. That only grows slowly over time. It is represented by a steep line that only moves left and right slowly. I suppose you could say that a financial crisis is when it moves left rapidly.

Corporate debt is a bit hard to track over the long-term, because American corporations are increasingly international. It is difficult to differentiate corporate debt between domestic operations or revenue and international operations or revenue. So, both corporate assets and corporate debt are rising over time as a percentage of GDP.

In Figure 2, you can see that corporate debt as a percentage of corporate assets has been pretty flat, in the low 20s, since the early 1970s. In the late 1970s and from about 1995 to 2005, corporate debt/assets declined. Then the ratio returned to that maximum level in the low 20s. Both periods where debt/assets declined were during periods where corporate assets/GDP were rising.

The Upside-Down CAPM way of thinking about this is that as corporations move along through an economic expansion, their asset base and earning capacity expands. This slowly expands their ability to supply deferred consumption by issuing low-risk debt securities. But, this happens with a lag. When corporate assets are expanding especially quickly, debt doesn’t immediately expand with it.

This presents the opposite of a Minsky or Austrian style cyclical model. Debt issuance, in the aggregate, isn’t increasing as part of a short-sighted, herd mentality that becomes increasingly risk-blind as an economy expands. It increases because there are more assets with stable values and earnings potential which can serve as collateral for deferred consumption. And debt grows more slowly than assets when asset values are rising because the market is generally risk averse, especially when asset values are volatile.

The last couple of decades have been a prime example of how the standard model can lead to erroneous thinking. This is the period of “ZIRP” (zero interest rate policy). And ZIRP supposedly was a policy of the federal reserve to push down borrowing costs, which increased corporate investment. (It is hard to argue that it increased investment in real estate, since it was associated with a steep decline in real estate leverage and mortgages outstanding. Or, I should say, it should be hard to argue that it increased investment in real estate.) This is an odd focal point for macro-analysis. The corporations that have been the drivers of marginal growth and rising stock market capitalization have not used debt. Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple. They are net creditors. Last I checked, the ten largest public corporations by market capitalization were net creditors - they collectively held more cash and investment assets than debt liabilities.

You can try to patch up that striking anomaly by claiming that lower interest rates flow through to expected returns on all assets. Frankly, I think the whole framework is a conceptual muddle. But as I discussed in parts 1 and 2, it doesn’t hold up empirically either. Expected returns on equities are not sensitive to real long term interest rates, and lower rates are associated with lower growth expectations.

Basically, as the economy grows, corporate asset bases grow, and the potential supply of corporate-guaranteed deferred consumption (low yield corporate debt) grows with it. The growth of low yield corporate debt is less volatile than the asset base that acts as its collateral, so the supply of low risk securities generally just moves slowly to the right. Its rightward movement is somewhat cyclical, but not particularly so.

Real Estate

Real estate is another form of collateral that can be used to supply fixed income. In a market with ample supply, that is also a steep supply curve that tends to move to the right slowly. When real estate is supply constrained, prices and aggregate values can become volatile. This has become the case in American residential real estate. This is one way to describe how NIMBYs caused the Global Financial Crisis. The potential supply of fixed income securities had moved to the right as real estate values rose, then it suddenly lurched to the left when they collapsed. In an amply supplied market, where valuations are mostly related to the cost of construction, that isn’t as much of a risk. Real estate valuations could only become so volatile in a NIMBY economy.

This is really counterintuitive. As you can see in Figure 3, volatile real estate values (and thus volatile potential supply of fixed income) is the result of years of declining residential investment (the blue line). When net residential investment was 3% or more of GDP annually, valuations were mostly a result of physical investment. When residential investment dropped below that level, volatile location value increasingly has driven aggregate valuations of real estate.

In the short term, the sharpest rise in valuations came during a relative building boom in the 2000s, so the rise in valuations (a lurching right of the supply of fixed income) has been falsely associated with high construction activity. The subsequent collapse (and a temporary lurching back to the left of of the supply of fixed income) has been accepted as the natural comeuppance of that mini construction boom. But, at a meta level, the volatility comes from the very low level of residential investment over a longer period of time.

You can see in Figure 3 that this is happening again, and the definition of a building boom keeps getting pitifuller and pitifuller. Now, the rise in real estate values associated with cyclical growth is happening with net residential investment (investment in structures minus depreciation of existing structures) of about 1% of GDP.

If you have a demand-focused model of investment, then you want to solve the rightward and leftward lurching of the potential supply of fixed income securities by clamping down on liquidity. Regulate real estate equity to be illiquid, slow monetary growth, slow down bank lending, etc. All those things are making the problem worse.

In Figure 4, we can see an upward drift in Real Estate asset values and mortgages as a percentage of GDP over time. This is for different reasons than the rise in corporate debt. As outlined above, this is because of inflated values from underinvestment.

The sharp rise in mortgages/RE values has some parallel movement to the rise in corporate debt/assets. In real estate, there is one big jump during the 2008 financial crisis, which is due to the collapse in asset values.

The debt/asset ratio in real estate isn’t quite as flat as the corporate debt/asset ratio. I think much of the rise from the late 1980s to the mid 1990s is related to changing tax rules that favored mortgage debt over other kinds of household debt. That has likely been somewhat reversed over time, though its effect on mortgages/RE values is swamped by the other shocks that have happened in the past couple of decades.

There is more cyclicality in mortgage debt than there is in corporate debt. I think the main reason is that homeowners generally do not leverage up tactically. Many homes are owned debt-free even in times when they could be leveraged substantially on favorable terms. For the most part, homeowners don’t perceive a large risk-adjusted gain to tactical leverage on their homes. Debt reduction as part of their broader portfolio of assets and liabilities tends to be more important.

A Digression on the 2000s Housing Boom and Bust

There are homeowners who are credit constrained, who do pull cash from home equity when they can. But, I think most of the pro-cyclical mortgage growth is due to the use of mortgages in purchases. Aggregate mortgage leverage was about 36% from 1993 to 2006. There is a combination of cash-out refinancing, mortgages for purchases, and after 2003, disinvestment of unleveraged owners.

That last category has been greatly underappreciated during the pre-Great Recession period. As I pointed out in Building from the Ground Up, the 2006-2007 period was really weird. The conventional wisdom just tends to treat every set of players as reckless investors continuing the excesses of a bubble, all part of one “bubble” story, played out in stages. But during that time, the “bubble” was increasingly a bubble in AAA-rated securities - deferred consumption!

In the standard narrative, that all gets twisted and tied into a story of greedy securities salesmen, banks leveraging one type of security against another, and gullible investors “reaching for yield”. But, it would be really weird to have a bubble in deferred consumption. If you look at this from an Upside-down CAPM point of view, the CDO boom of “The Big Short” fame was a signal of an economy in distress.

The complex CDOs were the securities that blew up (securities based on bundles of other securities, or even synthetic derivatives of other securities). Why was that even a market? It was a market because there was a huge spike in demand for deferred consumption and the supply curve in Figure 1 just can’t move to the right that fast. The CDOs were a failed attempt at engineering more risk-free securities because there weren’t enough naturally occurring ones to meet demand.

Initially, some of that demand was from former homeowners, or homeowners who were selling out of expensive markets and buying in more affordable markets seeking a safe alternative to shift all that former home equity into. Eventually, it was just standard cyclical risk aversion because (as so many will tell you in hindsight) anyone could see that a contraction was coming. (The bubble had to eventually pop, as they would tell the story.) The players in “The Big Short” were so sure of a coming contraction, they staked everything on profiting from it. One way to describe what they were doing is that they basically were pretending to borrow capital, using derivatives, so that when real securities started to default, they could pretend not to pay it back and pocket the difference.

The “suckers” that ended up with the rotten end of those deals were savers who were simply trying to find risk-free securities to hold - to defer consumption.

The “reaching for yield” narrative paints them as the reckless ones. Basically, in hindsight, when the worst of the Frankenstein attempts at engineering risk-free securities failed, we could identify the investors who had bought them as investors who were not good at assessing risk-free securities. It’s sort of like if you had a pre-existing complaint about antelope being lazy, and you went on a safari where you saw lions take one down, and you generalized the outcome to all of antelope-dom. “These antelope are just getting too slow. I saw this coming. I could have told you.” It is a good example of how if a people share a strong enough inference about a narrative, any facts will do to fill in the details.

The CDOs and the synthetic CDOs should never have existed, because the Fed should have stopped trying to slow down the economy and driving sentiment into the ground. A growth mentality and a growth-oriented monetary policy in 2006 would have limited the CDO market from forming. But, good luck trying to get an audience for that story in 2006 or 2007, let alone today.

Another way to think about this is that a supply-starved, price-inflated housing market will increase both the supply of deferred consumption (rising mortgages outstanding as a percentage of GDP) and demand for deferred consumption (cashed out sellers).

The normal way of looking at this led to a consensus that all of that was just part of a bubble. But, this leaves some odd facts that have mostly just been ignored. By 2005, the yield curve was inverted. In other words, sentiment was driving yields down. High yields are usually correlated with optimistic sentiment (see the late 1990s). CDOs were created because there were too many savers and not enough borrowers. The CDO boom happened during a deep decline in housing starts and sales. The Fed was sharply curtailing the growth of the money supply.

The Upside-down CAPM makes it all make sense. Before 2006, there was a moderate boom because we really needed more homes, and homes were especially expensive in some regions because we couldn’t build them. The supply (mortgage borrowers) of deferred consumption was rising, but so was demand for deferred consumption. By 2006 and 2007, misguided attempts at undermining a housing bubble slowed down the growth of supply and sped up the growth of demand. Unprecedented markets in financial engineering cropped up to try to bridge the gap.

Those securities get blamed for the crisis that followed, but really they were more a symptom of the unquenchable desire for a crisis than a cause of it. They really didn’t have much to do with the construction boom that preceded them. Maybe if they had been prevented from existing, the crisis would have come sooner and been less devastating. I’m not so sure. I suspect the main way they made the crisis worse was by making its initial victims unsympathetic and the crisis more popular.

Even as I write that, I don’t quite know how to explain it. Who was unsympathetic? Savers who were trying to prepare for future consumption needs, and who were faced with a shortage of legitimate risk-free assets to use for that intention. You know. Those assholes.

Deferred consumption requires a financial sector. To a large extent, facilitating deferred consumption is what the financial sector does. So, there were plenty of bankers, executives, employees and institutions that could be referred to as “Wall Street”, to plug into the narrative as the bad guys. It’s not hard to populate the narrative with characters that the audience can view unsympathetically.

One way to compare the Covid event with the Great Recession is that Covid was an event where policy was built on a consensus of shared sympathy. The Great Recession was built on a consensus of the lack of it. We collectively built economic narratives as we navigated these events that were meant to create or destroy sympathy. Again, something I outline in Building from the Ground Up is that one thing that everyone from Rick Santelli and the Tea Partiers to the Occupy Wall Streeters had in common was an explicit and all-encompassing opposition to sympathy. If only they had the Upside-down CAPM to guide them. :-/

Conclusion

In summary, looking back at Figure 1, flip debt upside-down as a capital class. The consumer is the saver, and they are seeking to consume in the future. The lender must have some dependable source of future value in order to provide that service. Demand is highly elastic, but can move up or down from changing economic and demographic conditions, and supply is highly inelastic, but can also move left and right from changing economic conditions.

This is not a case of different short-term and long-term elasticities. The changes in supply and demand are not a function of price and quantity. They are a function of changing sentiment, changing collateral values, etc. The supply and demand lines move around based on other factors in the economy.

Why does it matter?

For instance, this model would suggest that the recent rise in long-term real interest rates is from a shift down in the demand for deferred consumption. It is not likely that such a rise in rates came from the increase in public debt (an increase in supply) or Fed machinations (an incoherent muddle).

Debt demand-focused models would say that stabilized business cycle and stable asset pries will lead to more reckless borrowing as recency bias leads asset owners to overleverage. The Upside-down CAPM suggests that stability will moderately increase the supply of debt because of the expansion of collateral, but it will be associated with higher yields because improved sentiment will lower the demand for deferred consumption.

In large part, the quantity of debt is determined by the size of the economy, the size of the public debt, and the amount of home equity that can be used as collateral. The price of debt is determined by sentiment and demographics.