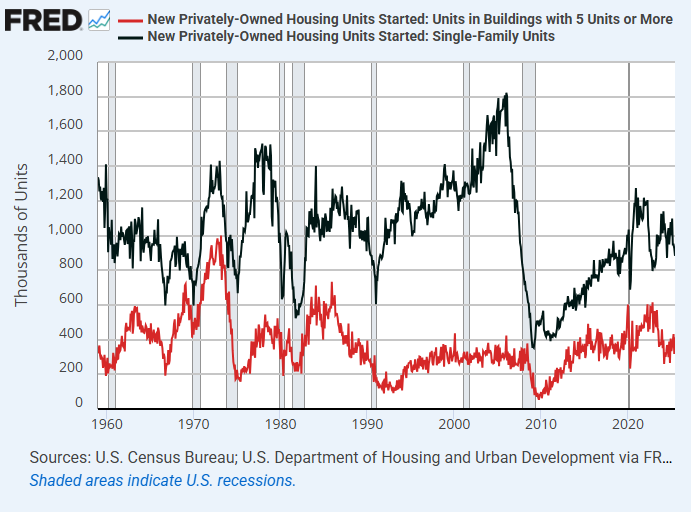

Continuing the discussion of housing and the business cycle, let’s walk through how patterns have changed over the past 65 years.

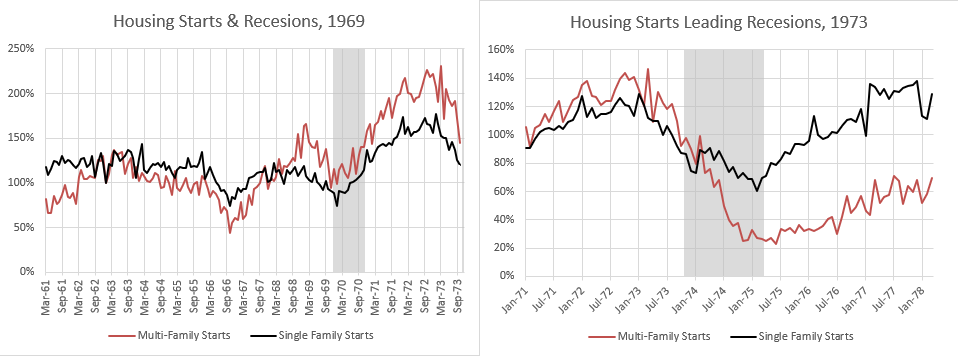

Figure 2 shows trends in housing starts for single-family and multi-family housing in the recessions of 1969 and 1973. What I would note here is that the impulse is similar in both multi- and single-family activity, in both time and scale. Declining starts lead the recession in both, and recovery signals the end of the recession in both.

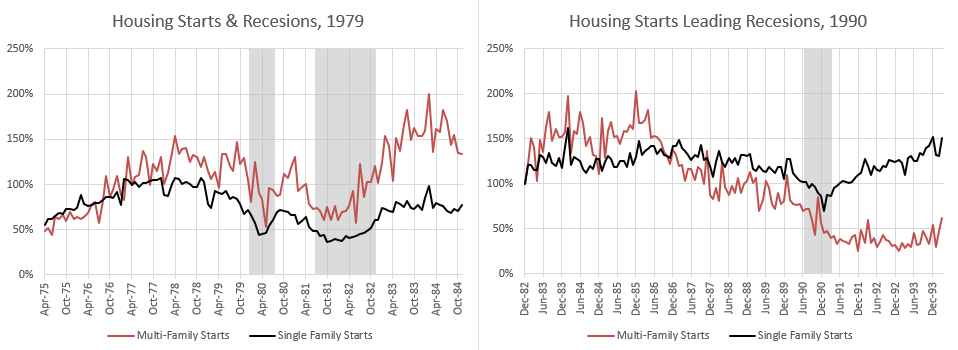

This continues in 1979 and 1990. However, in the 1990 cycle, the decline was very protracted. And multi-family starts never fully recovered to mid-20th century rates of activity.

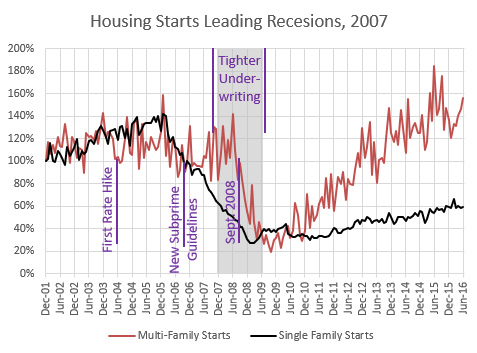

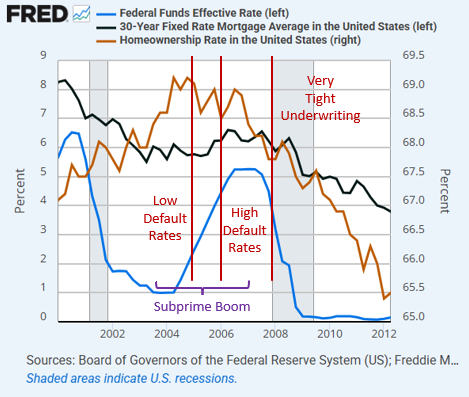

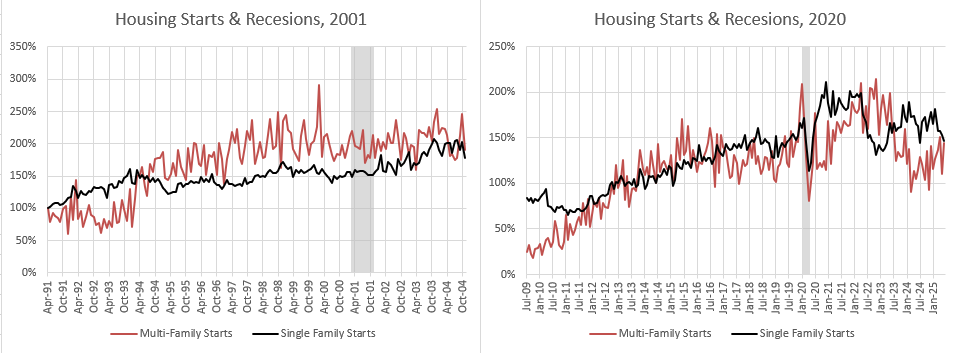

There wasn’t a housing downturn in 2001. Then, came the strange beast that was 2008. Really, as I view Figure 4 with fresh eyes, I think you can see a legitimate slow-down in 2006, shared among single- and multi-family. That was related to Fed policy. You can see the divergence between single- and multi-family activity in late 2006 or early 2007, which coincided with the end of the subprime boom.

Maybe I can add some nuance to my general story of the 2008 cycle.

2006: Normal, mild cyclical housing downturn.

2007: Transition from single-family to multi-family construction because of the correction in privately securitized mortgage lending markets. The cyclical downturn was over, as signaled by the stabilization of multi-family starts.

2008: The mortgage crackdown in the federal mortgage agencies, which further pushed single-family activity into a deep and novel decline while multi-family activity remained stable. By September 2008, the effect of the agency crackdown and the Fed’s ignorance of the depth of the damage from it finally caused a broader crisis and market crash, and multi-family activity finally crashed, not because of housing market conditions, but because of a general financial breakdown and sudden lagged deepening of the recession.

2009 and after: The mortgage crackdown now made the downturn in single-family construction permanent while multi-family construction recovered.

The story about what caused the 2008 crisis had already been carved in stone by 2006, and any details that didn’t match the story were universally ignored. To this day, oddly, some people continue to believe that the crisis was caused by rate resets on floating rate mortgages because that story had been written by 2006. The mortgages that had high default rates were generally taken out when rates were at their highest and then interest rates declined precipitously. See Figure 5. But, the story was written.

The trends in multi-family housing starts are really weird. No previous cycles looked like this. Multi-family starts are a leading indicator. That indicator stabilized by the end of 2006, in spite of the Fed’s refusal to lower its target rate and loosen conditions. Multi-family starts didn’t signal a downturn. In this cycle, the crisis in September 2008 acted on multi-family construction. The recession caused the multi-family downturn.

That doesn’t happen. And, if the story of 2008 hadn’t been carved in stone by 2006, serious people would have been wondering why it happened this time. There were no serious people by 2008.

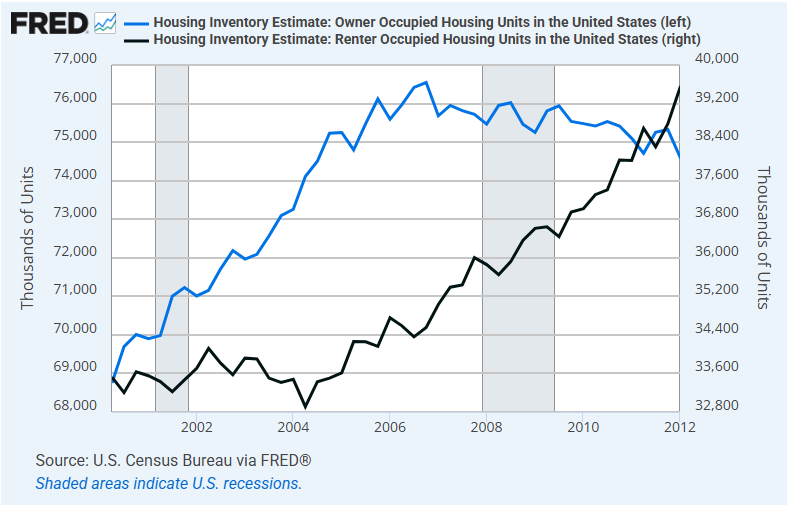

Around 2004 or 2005, there was a shift. Before then, a bit more than 1 million households were becoming homeowners each year. By the end of 2005, even while the private securitization boom was hot, that flatlined. After 2004, there were about 1 million households a year becoming renters. (Figure 6).

That’s kind of a problem in a country that has legislatively limited new multi-family housing at about 300,000 units annually. That meant that 700,000 existing or new single family homes had to be constructed or transitioned to the rental market every year.

And, this country was united around the goal of ruining the 700,000 investors that would be required to meet that demand.

Multi-family construction was resilient, right up until the crisis metastasized in September 2008, because multi-family construction couldn’t even begin to meet demand for rental housing. Not even close. It took a September 2008 to kill it. The financial sector had to be utterly neutered to stop multi-family housing from recovering.

Single-family construction was neutered in 3 steps - the original Fed rate hikes, the elimination of private subprime lending, and then the elimination of 1/3 of the traditional mortgage market.

Multi-family construction wasn’t targeted. Since it is kept in check by local municipal obstructions, it wasn’t viewed as out-of-control. (You could argue that, in several respects, single-family construction appeared to be out of control because of the lack of adequate multi-family housing.) So, it remained strong until the crisis killed activity both inside and outside the housing market. And then it recovered relatively quickly back up to its low cyclical ceiling after 2008.

The 2008 cycle should have looked not much different than the 2001 and 2020 cycles in Figure 7. A small dip in activity in 2006 that recovered in 2007. The trend in multi-family starts before September 2008 was the trend all housing would have followed without the moral panic.

In 2025, this is what we should expect. 2001, 2008 (without the moral panic), and 2020. This is the 21st century business cycle. This is the business cycle with a housing shortage.

Even with all of the dislocations since 2020 - a global pandemic, double digit inflation, whipsaw interest rates, bloated construction timelines, etc. - total production has been flat, and volatility has been mostly about trading market share between single- and multi-family starts.

It would be very difficult to get total starts to decline under these conditions. With each successive cycle, the shortage has gotten worse. Residential investment is no longer a leading indicator. And, maybe, recessions will be rare and shallow because declining residential investment had been an important trigger creating recessions back before we had an endemic housing shortage, but isn’t now.

Housing starts will increase as capacity allows. Eventually that will moderate rent inflation. It could be that we will move from a regime over the last 30 years where the Fed was persistently too tight and overly cyclical because rent inflation was high, to a regime where they will err on the side of being too loose and less cyclical because rent inflation will be low.

Hey Kevin. I recently ran a query/prompt on the free older version of Grok. In the previous series of questions I had asked Grok why the mutual-type method of founding an organisation or association had fallen by the wayside (it was obtaining capital for investment which was the problem for the mutual associations, but the main reason I mention the preceding questions because with Grok prior questions can play a major role in any subsequent prompts).

Anyway, I asked a question about the problems of the inefficiencies of the government approach to affordable and public housing versus a model of civic society associations backed by philanthropy and a charitable status to the donations, plus a tax rebate. The results were astoundingly good and drew on direct examples from the UK.

Here is the summary from a Discourse forum in which I participate:

'In the government model a house cost £63K to build. In the philanthropic model it cost £45K. This translated to 2,222 homes built, rather than 1587 homes. The system only cost the taxpayer half the money spent! Grok compared £100 million of taxpayer money spent versus a £50 million rebate on £100 million of charitable giving. The overhead losses were £15 million for the government sector, compared to £5 million for the charitable sector. I specifically stated I wanted to help the working poor, and Grok calculated that with the philanthropic model 80% would go to the working poor, compared to 50% for the government model.'

As you can see, per tax dollar spent, this actually results in 4,444 homes versus 1587 homes, although obviously obtaining the philanthropic donations are also vital. One of the reasons why Grok seemed to think the model worked so well, was because in the UK the charitable approach to homebuilding is allowed to access considerable regulatory relief. The philanthropy/civic society model also appears to be more innovative in the solutions it tends to seek, at least in the UK.

I asked Grok again, and it gave me this blurb: 'In summary, organizations like Peabody, Clarion Futures, and Habitat for Humanity, supported by land charities like the CLT Network, HACT, and the Nationwide Foundation, demonstrate that philanthropic and civic-led approaches can deliver affordable housing more effectively than government-run programs in many contexts. Their ability to combine community focus, innovative funding, and regulatory relief allows them to address local needs with agility and impact.'

Anyway, I just thought you might find it interesting given your focus on the shrinking share of Americans who will be able to access the American Dream of owning their own home. A philanthropy/civic society approach might act like a ladder for working people excluded from conventional mortgages because of their credit score, and I would imagine there are a fair number of very wealthy or rich Americans who would relish the opportunity to deprive the American government of $500K taxes paid through a tax rebate, in return for a $1 million donation to a civic society which takes the ability to build more bureaucracies away from government.

Hello! Great piece. As you know, I believe that perverse bank regulation explains much of the strange behavior of the housing market over the past 4 decades.

One hypothesis I have is that post-financial crisis bank regulation contributed greatly to our housing shortage. Regulators effectively put the kibosh on bank construction lending. You can see this in bank construction lending trends in the FDIC stats and I have much anecdotal evidence to support the hypothesis. My argument is that this prohibition starved the small independent builders of credit and forced many out of the business. (The large national builders have become largely self-financing.) The upshot was (and remains) that many smaller lots that would have been built on in the past are not developed. The big guys won't bother. Does this make sense to you and do you have any evidence one way or the other?