Interest Rates Aren't The Problem

I will walk through why rents are what is making housing unaffordable, not interest rates. And, I might complain a bit at the end about how attribution error makes unstable mortgage markets more popular than they should be.

It’s the rents, not the rates.

A lot of investors have been caught off-guard because they commit the common error of attributing mortgage rates to Fed policy choices and then over-estimating the effect of mortgage rates on home values. It leads to poor decisions in housing, specifically. More broadly, it leads to poor asset allocation decisions because investors expect a repeat of 2008, to some extent, and they become too risk averse, or simply miscalibrate the more important factors that will lead to positive or negative outcomes going forward.

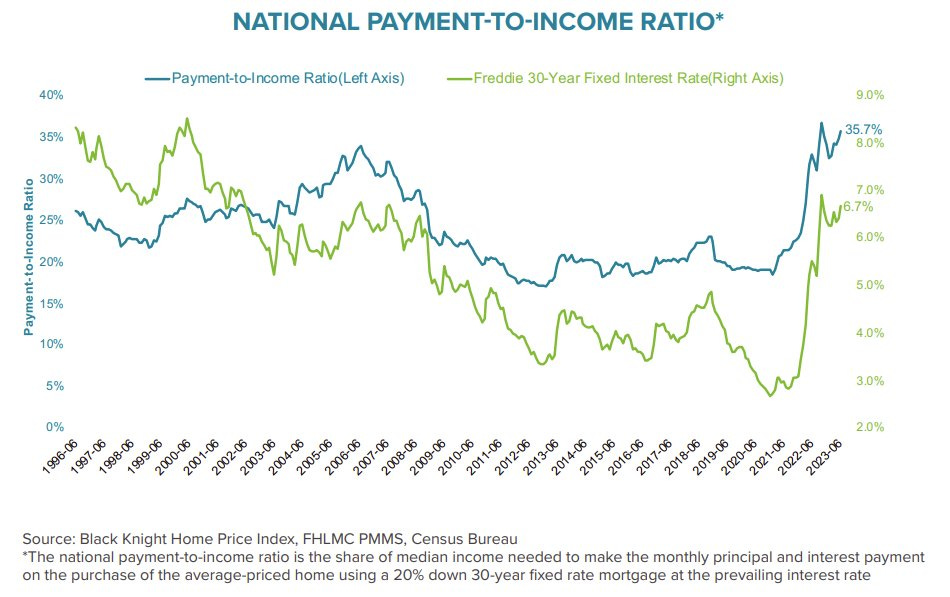

You can’t swing a cat without hitting a chart these days bemoaning how high mortgage rates have made housing unaffordable, and so something has to give - either rates must decline (presumably under the Fed’s control) or home prices will need to decline dramatically. This is technically true. And, certainly, on the straightforward question of “What changed over the course of 2022?” the answer is clearly that, the mortgage payment for the average family on the average home went up a lot.

From the errant point of view, this is confusing. Homes were supposedly expensive because the Fed has spent decades stimulating artificial demand with low interest rates. Now the causal factor is gone. Something has to give.

It could be that interest rates will once again fall to the zero lower bound. I think we’ve got a live one with JPow, though, and he may just keep the economy chugging along with rates back at higher levels. If rates don’t fall, then we will not see mortgage affordability like the 2010s again for decades, if ever. It was an anomaly. A temporary period where the haves were buying underpriced homes with temporarily low mortgage rates, and those homes were selling at below market because millions of former buyers couldn’t get those mortgages any more, thanks to the CFPB, FHFA, Paulson, Dodd, Frank, Warren, etc.

That was only temporary. Rents inevitably had to rise until home prices rose above replacement cost, which, in many places, where private investors are finally buying rental neighborhoods from builders, it appears they finally have. This may finally slow down rent inflation, if we let it.

It is those high rents that make housing unaffordable relative to historical norms, not high interest rates. Here is a simple model of housing affordability through which to think about this.

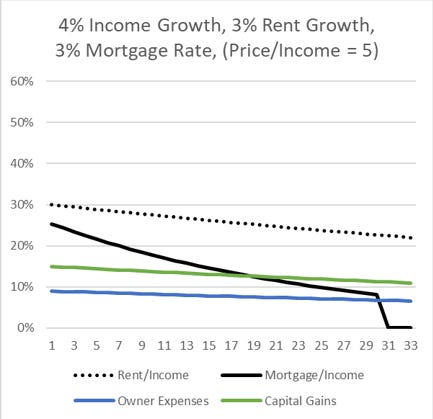

The following charts are based on a baseline economy with 4% nominal per capita income growth, 2% general inflation, and some other variables I will play with. Home prices here are mechanically determined by rent inflation to roughly reflect the patterns I highlight with the Erdmann Housing Tracker.

These charts track the cash flows and expected capital gains over 33 years for a given family in a given house, whose rent at inception takes 30% of household income.

Figure 2 is basically the 20th century American deal (briefly interrupted by 1970s inflation). You can rent the house for 30% of income. If your income increases by 4% annually and the rent increases by 2% annually, that amount slowly declines.

Or, you can buy the house. It will probably be priced at around 4x your income. The 2% capital gains, over the long term, will roughly track the 2% annual inflation in the rental value, and your annual maintenance and upkeep will probably be in the same range as the capital gains. Of course, both the expenses and the capital gains come in fits and starts, but this is the basic average picture over your life in the house.

In that context, the starting mortgage payment will be similar to the rent payment, but over time, it will decline because the mortgage payment is fixed while incomes and rents tend to rise. That gap - the slow decline in costs and accumulation of home equity - is the proverbial American dream. It’s actually pretty boring.

But, a handful of cities throttled housing supply, and so they broke that boring dream. By the turn of the century, the Closed Access cities looked something like Figure 3. You could rent a house where rent took 30% of your income (which, by the way, was a lot less house than you would have gotten in a normal city), or you could buy it.

But, in this context, with persistent rent growth of 5%, the price of the home will likely be more like 7x your income. Most of that extra value comes from the distant future, because the rental value will increasingly take more of your income rather than less. (This is the condition of upward filtering that inadequate supply leads to.)

This condition exaggerates the mismatch between mortgage cash flows and rent cash flows. In the boring “American Dream” scenario, the front-loaded cash outflows of a mortgage was benign because it never required much more cash than rent would. But in the supply constrained scenario, the difference is stark. The cash outflow for the mortgage is nearly 60% of the buyer’s income when rent would only require 30%. At the same time, the expected capital gains are more than 30% of the buyer’s income.

This would sound absurd if there weren’t millions of homeowners who had experienced exactly this sort of outcome. This creates at least two problems. First, the Dream is gone, and what is left is this nasty situation where the closest you can get to the Dream is speculating on what is now a wildly volatile stake in your local housing cartel. Second, to claim this horribly second-rate Dream, you have to take on highly stressful temporary levels of cash outflows. Either this all blows up in your face, or in 20 years you’re increasingly shielded from your city’s rising rents. By then, your city will be populated by residents who either can’t afford the rising rents, or who couldn’t afford them if they had to pay them.

This is why it’s incredibly frustrating to see the cliché that “Housing can be affordable or it can be a good investment, but it can’t be both.” or to see antagonism about programs meant to make mortgages more accessible as if they make housing less affordable. The problem is with supply and rent inflation. Everything worked just fine when housing could be built. Even in 2005, it was working just fine in two-thirds of the country. Don’t observe these ridiculous markets and then turn it into some universal truth of the housing market. For decades, generous mortgages allowed families to buy affordable homes that were good investments. If you let the context of Figure 3 turn you against any of that, you’re a bad person and you should feel bad about yourself.

For a while, after the 2008 crisis, buying a home was a steal for the dwindling number of Americans who were cash rich or still under the good graces of federal mortgage regulators. That was an anomalous time, and mortgage affordability will likely never be so good again.

By the time Covid came around, supply had been constrained, nationwide, for long enough, that rents were rising, and home prices with them, so that, nationwide, 3% rent inflation was normal, which leads to a price/income ratio of 5 in this simple model, and mortgage rates were around 4%. That’s Figure 4.

This was a broken market, but if you’re just naively tracking “mortgage affordability” it looks normal. To buy the home that would rent for 30% of your income, you need a mortgage that takes 30% of your income. But, here, the deal was much better than it traditionally had been. Rising rents meant rising home values and capital gains. And it meant that the gap between the cash outlays of the mortgage and the cash outlays of renting widened much more quickly than it does in a healthy market.

This is where a lot of real estate investors made bank, too. If you had the capital, the gains were there for the taking, either as a homeowner or as a landlord.

Then, by 2020 and 2021, after the Covid shock, mortgage rates fell, and the value proposition for owners got even better, in Figure 5. Now the cash outflows of a mortgage in many places, right from the first payment, were typically well below the rental payment for the same home.

This is not the appropriate place to benchmark your expectations for mortgage affordability. That’s the main problem with the breathless claims that the mortgage required to buy the median house has doubled, or some such. A lot of that increase was a return to normal, under any imaginable expectations about what a house should cost.

And, so now, a simple model of the national housing market, in Figure 6, is that rent growth is still 3% with price/income of 5, but the 30 year mortgage rates is 7%. The only difference between this scenario and the American Dream in Figure 2 is that rent inflation is higher.

So, the relative price of the home is higher, and every urban home in the US is now a bit closer to the Closed Access hellscape of Figure 3. The mortgage cash outflows are frontloaded, and in return the buyer gets access to volatile capital gains over time. The individual political actions of existing residents across the country to force stasis in existing neighborhoods is the root cause of this problem, but nobody actually wants this. We want Figure 2. We want the Dream. Which is why top down state limits on housing obstruction are necessary to get back what we had.

Illiquidity for dummies

But, there is another aspect of this situation that deserves discussion. High prices and high rates only lead to an affordability problem because the cash outlays required by our traditional mortgage products are so frontloaded. There is no reason they need to be frontloaded like that. I published a paper at Mercatus proposing a mortgage amortization product that could flatten that pattern.

Isn’t it weird that in all of the concern about affordability, seemingly nobody suggests doing something about those frontloaded cash outlays?

This is one of the factors that became important in the 2008 debacle. Figure 7 shows a Closed Access city, similar to Figure 3, but here I have added a second mortgage option - an interest only mortgage (using the 30 year rate).

Residents in these markets were in a stressful, dysfunctional condition. The use of unstable mortgage products with teaser rates, negative amortization, etc. didn’t really cause that stress and dysfunction. They were a product of it. They were attempts to alleviate the front-loaded cash outflows that traditional buyers must deal with in a market with broken supply.

Note, even the buyer with an interest-only mortgage has much more front-loaded costs than the renter does, and the interest-only buyer has a hedge against future rent increases. Of course, in exchange, they must be vulnerable to volatile capital gains.

The common reaction to this problem is to impose illiquidity on the housing market. As if too much liquidity is the buyer’s problem. For Pete’s sake, what nonsense. Oh, but the rending of garments one sees whenever lenders propose lower down payments, longer amortization schedules, or some other term meant to alleviate the front-loaded cash outflow problem. Or, preventing owners from accessing home equity is another favorite policy meant to tie the arms of home buyers and home owners, again, as if their problem is too much liquidity, and they require us to keep them disciplined and cash poor, as if that is the way to get from Figure 6 back to Figure 2.

I think that is partly why the 30 year mortgage is popular. It front-loads the cash outflows and makes home buyers less liquid, and nothing makes a policy more popular in housing than limiting the housing others can demand.

The intuition to make housing affordable by making buyers illiquid has arguably caused a lot more damage than the regional Closed Access land use regulations have. It deserves more attention. And, in the current environment, where the salient complaint of the day is the high cost of buying a home with a mortgage, it is the dog that isn’t barking. Nobody dares to suggest fixing the problem by backloading some of those cash outflows. That would be reckless, so instead, you should be denied any mortgage product so that every year, you get to guess how much your landlord is going to jack up your rent in our broken market. It’s only prudent, says we.

Spot on. Unzone property, let it rip.

This problem of unaffordable housing in developing nations is spreading. Canadian social media is aflame with angry people talking about rents, house prices, and that they will never be able to buy a home in Canada, or even afford rent, on middle class incomes.

I am getting the sense unless developed nations place a priority on robust housing construction, then housing markets go screwy. Of course, in Singapore 80% of housing is public housing, but most people say they have good government (and model citizens too).

As always, Japan is the exception. After rents, the average resident of Sapporo Japan is much better off than US residents in housing restricted cities, or almost anyone in Canada.

But if you chart per capita income, it does not look that way.

I think the causality runs from bad land-use regulations to bad lending policies. Several generations of Americans, including bankers, have held onto the madness that a single family house shall always appreciate in value at a rate that exceeds inflation. The structural damage done by large lot, single family zoning in the ring suburbs of closed access cities is too profound to be solved with better lending policies. However, I do support policies that increases housing abundance of any type--which has always been one of your consistent points. If we build more rental units, the impact is positive across the spectrum.