Inflation: Everyone is right.

Mike Konczal at the Roosevelt Institute has an interesting post up about the current causes of inflation. His analysis suggests that supply constraints are important. I will contrast this with Scott Sumner’s recent post at Econlog. Scott has been critical of the Fed’s role in allowing inflation to recently rise.

Supply-Side Disinflation

One of the methods Konczal uses is based on basic supply and demand intuition. If in a given industry, inflation is declining while real growth is rising, that suggests that healing supply constraints are pushing prices down. If inflation is declining while real growth is slowing, that suggests that declining demand is pushing prices down.

Here is the chart that conveys this approach. Basically, a lot of categories in the lower left quadrant point to declining demand while a lot of categories in the lower right quadrant points to rising supply capacity.

As you can see, in goods sectors, there is a very strong supply recovery story. The story is a bit messier in services, but, viewed closely, there are a lot of service sectors that are below the origin and either right on the y-axis or in the lower right quadrant. Only a few are in the lower left. Konczal estimates that services, in general, fall more on the side of supply recovery.

This certainly seems to be tenatively confirmed by the Atlanta Fed’s forecast for very high real GDP growth in the 3rd quarter.

He concludes, “at the moment, the inflation story is exactly what a ‘soft landing’ would have predicted. A combination of resolving supply shocks and a subtle decrease in demand has driven inflation down dramatically, with no cost to the level of employment. Patience, and letting the data unfold, is the most important objective for policymakers right now.”

Demand-Side Inflation

Sumner begins, “In 2021, some economists predicted that high inflation would be transitory. When inflation soared much higher in 2022, those claims looked foolish. Now that headline inflation has fallen to just over 3%, some are asking whether inflation was transitory after all.”

He notes that the definition of transitory inflation is a bit slippery, and the shorthand he suggests using for transitory inflation is the trend in nominal wages. In other words, if there was just a brief supply shock that made some items more expensive and then reversed, that shouldn’t create any permanent changes in wages. On the other hand, if inflation was caused by a period of loose monetary policy that permanently increased aggregate prices, then we would expect wages to permanently rise also.

He points to Figure 2 as evidence that inflation wasn’t transitory. Prices are permanently higher because of a dovish monetary position. Wage growth increased and remains high.

I think this is basically correct. I generally would argue that inflation was transitory because it came down without the Fed’s help. But, it is true that the inflation didn’t reverse. There was a one-time bump. We are back to the trend growth rate but we are above the previous trendline in prices. So, the Fed didn’t need to intervene hawkishly to bring inflation down, but we probably must conclude that it did intervene dovishly to keep inflation from reversing.

In a nutshell, my assertion is that the neutral rate is a moving target, and it has been especially volatile recently. The Fed rate hikes mostly followed a rising neutral rate higher. The neutral rate was rising because the Fed’s policy of letting transitory inflation play out without trying to throttle it was a beneficial decision, and economic expectations improved because of it. Technically, the current Fed policy rate is too high, but the market has always expected that to be temporary, and as long as the Fed reverses it soon, it shouldn’t be disruptive.

Along the way, while the Fed was chasing the neutral rate higher, Fed policy seems to have hit the sweet spot - loose enough to avoid reversing the transitory inflation, but not so loose that prices kept rising.

I have written a lot about how the norm of using trailing 12 month inflation created confusion here. In Figure 3, I compare the Fed Funds rate (red), inflation expectations (blue), and CPI inflation (monthly in gray and 12 month trailing in black dashed). The inflation measures are on the right scale so that details of the other measures are more clear.

You can see that inflation expectations remained relatively stable, rising along with transitory inflation, but at a much lower scale. Inflation was always expected to return to normal quickly. Using the trailing 12 month inflation measure, it looked deceptively like inflation was slowly brought down as the Fed raised its target rate higher. But, as you can see with the monthly CPI inflation measure, inflation completely normalized by July 2022 and inflation expectations declined along with it when Fed rate hikes had only just begun.

In fact, the Fed policy rate was quite dovish by the end of 2022. The effect of 2022 Fed policy was not to lower inflation. That happened on its own. The Fed was most dovish during the period when transitory inflation was declining, and that dovishness kept inflation from declining much below the 2% target. (Inflation has been below target using my preferred CPI measure that excludes shelter inflation, but that isn’t the measure the Fed targets. The Fed targets PCE inflation, which generally runs a little lower than CPI inflation - in large part because rent inflation from our housing shortage has a larger effect on CPI.)

To revisit Scott’s point on wages, the ECI, shown in Figure 4, might be a better measure of labor costs than the average hourly earnings he cited, because the average earnings measure tends to be overstated when unemployment is rising and understated when it is declining. It gives a more neutral picture of wage inflation over time.

I agree with Scott’s point about the rise in wages confirming the Fed’s role in a permanently higher price level. But, I think there is less to worry about going forward. First, I think there is some wage stickiness. When inflation spiked (in Figure 4, I use the GDP price measure), wages lagged a bit. So, as inflation has returned to normal (the red line in Figure 4), wage inflation has turned lower too, but again with a lag. It is highly likely to continue to follow other inflation measures down.

Secondly, we are back to the trailing 12 month issue. The norm for all of these measures is to estimate the change from a year ago. In the current context, this causes all of the measures to lag current conditions. Here, I used the annualized rate of quarterly changes. This especially highlights the return to normal for GDP inflation. Most analysts will report the trailing 12 month estimates, which will be slower to pick up recent changes.

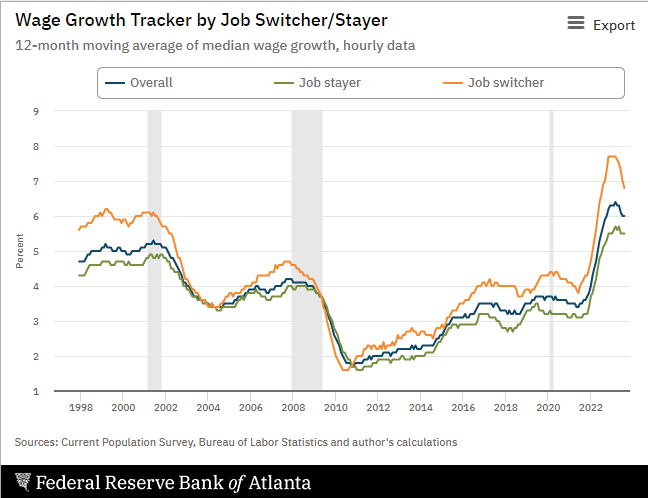

I would also highlight another compositional issue in wage inflation. This also probably causes average earnings to show more growth than the ECI measure does. There has been a lot of healthy churn in the labor market. You can see this in the Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker, shown in Figure 5. In the heady days of the late 1990s, workers were switching into new more productive jobs. At the time, wages in general were growing at about 5% annually, but for workers who switched jobs, wages were growing by 6%.

Quits and hires have been strong again recently. The reason your favorite restaurant can’t get enough waiters is that the waiters are finding better paying work elsewhere. This is great news.

Recently, wage growth has averaged a nearly 6.5%, but for job switchers, it reached nearly 8%. For job stayers, wage growth peaked at a bit under 6%. Job stayer wage growth should fall back to around 4%. That’s higher than it has been for most of the tepid recovery from the Great Recession, and it should be. But, it is still lower than it is now. Though, again, this is a measure that looks back 12 months, so we are probably already in better shape than it seems.

This is one way to think about Fed policy. Wage growth for job switchers that stays above 5% would probably be associated with a “soft landing” and grand times ahead.

In Defense of Fed Dovishness

I share Sumner’s affinity for stable nominal GDP growth as the most useful measure to guide Fed policy. Nominal GDP growth spiked after the Covid shock, which Scott reasonably associates with disruptive Fed dovishness.

I have argued that a 5% NGDP growth rate has been a long-term trend, which we fell from after the Great Recession, but that we might be in a position to follow that trend again. I think much of the post-GR decline in NGDP growth was related to the harmful policy choices that slowed down housing construction. As housing has slowly recovered, NGDP trend growth has recovered too. We are not currently far from a 5% NGDP growth trend dating to about 2016. That is in part due to the persistent recovery of housing, which will only stop if we force it to with overbearing policies meant to. And it is in part to Fed policy decisions which have allowed a one-time inflation spike so that the real shock of Covid didn’t become permanent.

I don’t expect anyone using inflation targeting or NGDP growth targeting to join me in this position. Using strict growth targeting guidelines, we have had an inflationary shock, and at the end of the day that is on the Fed. I am willing to celebrate the deviation, but it was a deviation.

There is a gray area between idiosyncratic relative supply shocks that are happening constantly in a dynamic economy and a systemic shock that could lead to broad unemployment, etc. Most systemic shocks have been monetary shocks. The Covid shock was different.

If it had simply been the case Covid caused supply chain disruptions in automobile production, then it would have made sense for general inflation to glide along at something near 2% while automobile inflation spiked and then reversed so that prices all reverted back to previous trends.

But, Covid created broad and complicated disruptions that were hard to pinpoint. That, in and of itself, led to a bias toward inflationary policy, because this time really was different, and there was a lot going on in 2020. Much of that was triggered by fiscal policy decisions. Even on those grounds, it was reasonable for the Fed to aim for price trends that remained at the new higher trend.

But, then came the Ukrainian war and follow-up waves of Covid disruption that seem to have mainly affected Asian production. And, supply shocks added up to 10% of inflation over about 2 years. At its base, this was still a supply shock (and even inflationary fiscal policy was a reaction to the supply shock). However, at some point, the scale and length of a supply shock makes a reversal impractical.

I suppose there are costs to a permanent rise in the price level, but there are costs to lowering the price level too. And, as I noted above, one could argue that even though it came with a price shock, that was part of the process of reattaining a healthier growth path.

A Note on Housing

Finally, a note on housing. This connects back with Konczal’s analysis. A large portion of the categorical trends he measured have seen little change in supply trends but a decline in inflation trends. He included those categories, tentatively, in his estimate of disinflation related to loosening supply.

He also offered up the hypothesis that these are categories that have been on a vertical supply curve, so that changes in demand acted purely on prices. I think this is the more likely explanation. This means that the Fed had allowed nominal spending to be inflationary. Consumers were attempting to spend more where supply was already at capacity. As nominal spending has declined, production has remained at capacity while prices have declined.

This points to a reversal of textbook inflationary monetary policy.

I am sure that housing is one of those categories. Production remains at capacity. There is still potential for supply recovery, which the industry seems to be just stepping into. As shown in Figure 6, real growth of housing expenditures is stuck below 1%. In the 1960s and 1970s, this commonly grew by 5% annually during expansion periods, but even in our current pitiful state, 3-4% growth is possible.

So, housing is an example of Sumner’s complaint. Prices are declining from Fed policy that had been dovish enough to raise prices in a standard way - by pushing demand higher than capacity could match. And it is also an example of Konczal’s point. Supply is still constrained. There is still potential for prices to decline because of healing supply conditions.

Konczal’s analysis has a data issue that should be noted. Federal estimates of rent inflation are based on survey data of tenants. They are known to have a lag because existing leases change more slowly than leases on new rentals. So, disinflation happened earlier in housing than the CPI and PCE measures suggest. In Figure 6, I show the semiannual price changes in the PCE housing measure, and I also show the measure for price changes in the CPI, excluding housing. Rent inflation based on new leases, tracked by several sources, including Zillow, tracked along pretty closely with general inflation. So, true market price changes in housing probably look closer to the CPI trends in Figure 6 than to the PCE housing trends.

The inflationary spike came and went, and housing still needs to have its supply recovery. Transitory inflation is supposed to end when supply recovers, so this is actually a signal that the most recent Fed policy targets are pulling down inflation.

For several years, shelter (mostly rent) inflation has run about 2% hotter than general inflation because of the housing shortage. We should expect that to slowly decline as housing construction increases from here. But, it will require a lot more building.

There has been very little about either rent inflation or home price inflation that requires any additional explanations. Figure 7 is a version of a chart I shared on a previous post. Here, I have added to my chart crimes by fully scaling both y-axes. But, this isn’t just a random matching. First, I matched the CPI shelter measure to Zillow’s estimate of median US rent. Here I added 3% to CPI instead of 2% because the Zillow measure includes compositional changes as new homes are added to the housing stock. This was the established pattern before Covid, and you can see that the rise in rents during Covid did not diverge from that pattern.

There was a lot of regional housing activity related to Covid. This suggests that while those migration shocks might have had regional effects, they netted out to zero nationally. Previous relative trends in aggregate rents continued, both during inflation and disinflation.

The same is true of prices. A recurring topic at EHT is that home prices have more than a 1:1 relationship to rents when rents reflect arbitrary local supply constraints. Each 1% increase in rents seems to lead to about a 1.5% increase in prices. That is roughly the scale shown in Figure 7. It held strongly before Covid, during Covid, and after Covid. I would attribute the temporary deviations above the rent trend to the long queues of homes under construction at the homebuilders and the temporary equilibrium price related to high input costs and high builder margins that has mostly returned to normal.

This all leads back to a recurring theme here at EHT. If the Fed can continue to hold hawks at bay, there is a lot of remaining potential for supply expansion and real economic growth. In a way, we are still at the point of the recession where there is catch-up growth, but in the period between the recessionary shock and the catch-up growth period, we had this odd waiting period that included a 10%+ increase in the price level.

High real growth with low aggregate inflation lies ahead if construction capacity can recover as it has in the past, and if the Fed maintains a level of demand that uses that capacity. Eventually, slowly, that might lead to more vacancies and an end to our 3 decade-long bout of excess rent inflation. Some industry insiders might be afraid of that, but you and I sure shouldn’t be. And, the builders shouldn’t be either, because they have a heck of a lot of work to do.